By Mark Tanner*

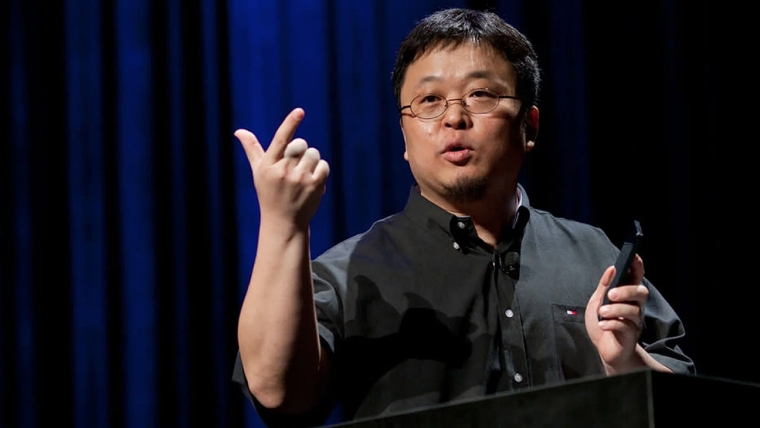

It began with a single Weibo post. On September 10, entrepreneur-influencer Luo Yonghao walked out of a Xibei restaurant and fired off the post to his millions of followers: “Almost all pre-made dishes. Still so expensive. Disgusting.” It look less than two hours for the storm to spread.

The war of words escalates

Xibei, one of China’s best-known northwest cuisine chains with nearly 400 outlets, 17,000+ staff and ¥6.2 billion ($871m) in annual revenue, suddenly found itself in open battle. Luo doubled down on livestreams across 11 platforms, insisting he wasn’t against pre-made food per se, but wanted transparency and consumer choice. He even offered a ¥100,000 ($14,000) bounty for anyone who could prove Xibei was using pre-made dishes behind the scenes.

Xibei’s founder, Jia Guolong, fired back. He accused Luo of defamation, vowed to take him to court (“We will definitely, definitely, definitely sue”), and rolled out a counter-campaign: the “Luo Yonghao Menu.” Customers could order the exact dishes Luo ate that night, with two bold promises: “Not tasty, don’t pay” and “Our kitchen doors are always open.”

In fact, on 12 September, Xibei opened its kitchens to all customers in more than 370 restaurants across China. Kitchen livestreams and on-site media visits swiftly revealed the use of frozen ingredients, such as sea bass with an 18 month shelf life and broccoli frozen for 2 years. Other issues included chefs using ladles to unclog drains, and chefs working without licenses. 2 days later, Xibei suspended the offer for anyone to visit their kitchens.

A Xibei Head chef, admitted to journalists that he did not have a chef license and questioned if this meant he couldn’t cook well?

The brunt of jokes

Sometimes memes can be positive for brands, but no brand would choose to bear the brunt of Xibei jokes that followed. Xibei carved out a strong niche appealing to young families: between 2019-2022, Xibei’s kids’ meals revenue grew 415%, but many of jokes were targeted at the kid-focus:

-

“Moms went to Xibei because they didn’t want to cook - it turns out, Xibei’s chefs didn’t want to cook either.

-

“A one-year-old eats two-year-old food”

-

“While the baby’s still in the womb, the baby’s meal is already waiting in the freezer.”

-

Even Luo Yonghao himself noted: “I expected many netizens would try for the 100k bounty, but never thought Xibei itself would want it,” referring to chefs admitting oversights.

Meanwhile, Xibei convened what social media dubbed a “war mobilization meeting” with its 18,000 employees. The company later clarified it was an all-staff call to reassure frontline workers: keep serving customers well, stay proud, stay motivated. But Luo posted the screenshot of the “mobilization” and mocked, “They still think I’m the enemy? Can these people be saved?”

The heart of the dispute

This fight isn’t really about Luo’s one dinner bill. It symbolises China’s dining psyche in the pre-made food era.

-

Price vs. Value: Xibei has long been accused of being “expensive”, with an average ticket of ¥85 ($12), far above other northwest cuisine chains like Jiumaojiu at ¥55 ($8). Luo stoked the fire by comparing Xibei’s ¥21 ($3) steamed bun to Michelin-star equivalents, calling the pricing “ridiculous.”

-

Brand Promise vs. Consumer Trust: For years, Xibei has positioned itself as family-friendly, healthy, freshly cooked. Its brand story relies on the perception of non-industrial, “real” food. Luo’s accusation of pre-made dishes - whether aligned with regulators’ strict definition or not - threatens to unravel that carefully built narrative.

-

Efficiency vs. Experience: Jia argues that industrialization and efficiency are essential in a low-margin, high-cost industry. But as one observer noted, “consumers don’t care about your back-end efficiency, they care about the front-end taste and honesty.”

Why it struck a nerve

Pre-made food is booming in China, with the market doubling in just three years. Regulators have tried to clarify definitions: pre-made means pre-cooked and packaged dishes requiring only heating. Yet in the public’s mind, the line between “freshly prepared” and “industrialized” has blurred. Distrust runs deep.

Consumers don’t necessarily reject pre-made food itself. They reject being misled. That’s why brands like Lao Xiang Ji have gained credit by publishing full transparency reports, detailing which dishes are fresh, semi-pre-made, or fully reheated. In contrast, companies that deny, deflect, or appear defensive risk losing not just a debate, but their credibility.

What it means for brands

The Luo–Xibei battle is a high-profile skirmish illustrating the tension between industrial efficiency and consumer authenticity, at a time when prices are increasingly under pressure with consumers.

-

For restaurants: Transparency may be more valuable than denial. With perceptions of pre-made vs. fresh becoming increasingly polarized, consumers expect honesty.

-

For brands: Protecting the “emotional value” of food is as important as protecting its safety. A single influencer’s punch can destroy years of brand building.

-

For the industry: Quietly sliding pre-made components into “fresh” menus are increasingly likely to be called out. With consumer watchdogs like Luo, it pays to be transparent.

The bigger picture

Luo Yonghao insists he’s not waging war on Xibei, but on opacity. Jia Guolong says he’s defending his company’s honour. In reality, it symbolizes the push for standardisation versus the demand for authenticity.

Consumer preferences are unlikely to hang on the result of lawsuits or livestreams, but on whether brands can bridge the widening trust gap. It represents a wider trend about brands resonating in China: not those that are preparing in a specific way, with specific inputs, but the ones that are most transparent about it.

*Mark Tanner is the CEO of China Skinny, a marketing consultancy in Shanghai. This article was first published here, and is re-posted with permission.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.