By Brendon Harre*

The point of incremental change is to grease the machine to make a more efficient model.

In contrast radical change requires governments to move past current practice to create an entirely new system better suited to the obstacles presented.

Note — email address depicted is not current.

See full letter below.

As my family and friends know, I am more than a little obsessed about housing. I believe, and have done for a long time now, that our cities and towns are profoundly broken. The poor way New Zealand manages the built environment risks making the housing crisis an obstacle that might prove insurmountable. That has awful flow-on effects for a myriad of issues, including: climate change, inequality and poor productivity.

My earlier papers in the Rack-Rent Housing Crisis series described how bad the current housing situation is and outlined what I thought should be done. This article builds on that by providing my personal history with the housing crisis; it provides a big picture view and a rationale for what I think the government will do next.

Back in 2007, I had experienced two stints living in Europe for extended periods and knew housing quality and pricing in New Zealand could be much better — it was not just housing, the whole urban package could be better. I wrote to then-Finance Minister Michael Cullen expressing my concerns and he was good enough to provide a considered response, unlike many other politicians I have approached over the years.

Judging from his reply, back in 2007 Cullen was reflecting on the housing situation and had some uncertainty regarding the best response. Readers can make their own judgments as a transcribed copy of the letter is included at the end of this paper.

To me, it showed Cullen had a broad understanding of the many factors influencing the housing market — he would be in the ‘no silver bullet’ camp.

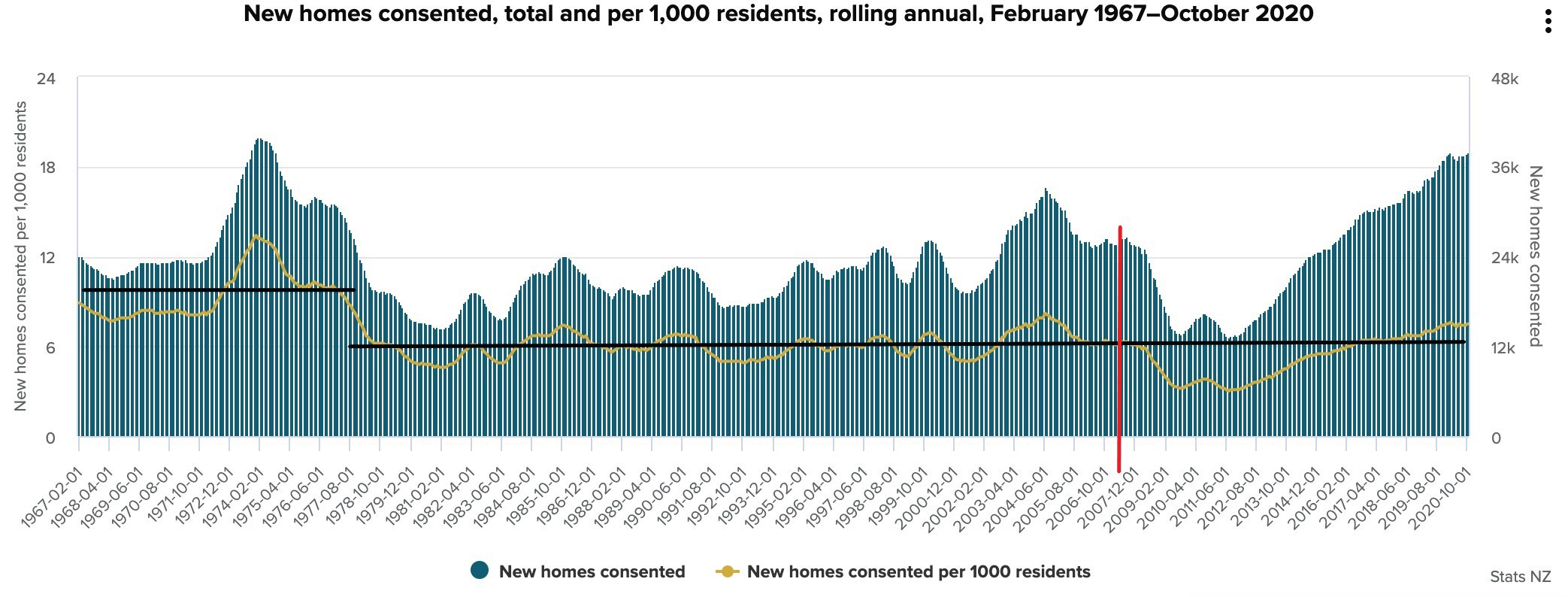

Total housing construction is at record highs. Yet, on a per capita basis the build rate has only recently returned to the 1977 to 2007 construction rate. Per-capita construction was greater in the decade from 1967 to 1977. Source

In the immediate period after 2007, demand was the most obvious influence on the housing market. The global financial crisis (GFC) flattened house price increases for several years, but supply did not catch up to demand. Housing construction slumped, so when demand returned in the mid-2010s prices and rents ratcheted up again. The median house price went from $345,000 in July 2007, when I raised housing supply concerns with Cullen, to $810,000 in April 2021.

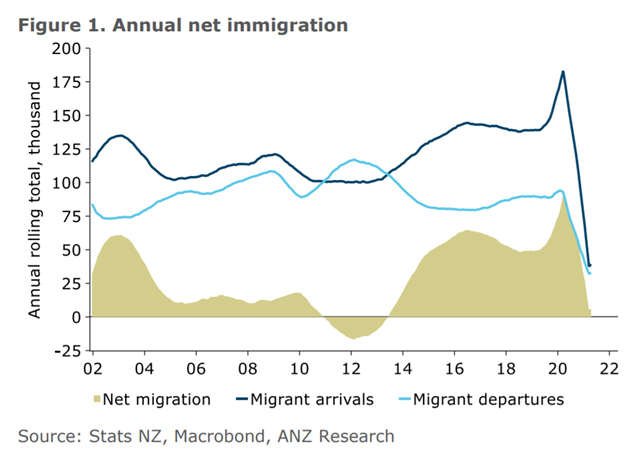

A significant demand stimulus from 2015 was high net migration numbers.

Source: ANZ Research: How does immigration affect the New Zealand economy

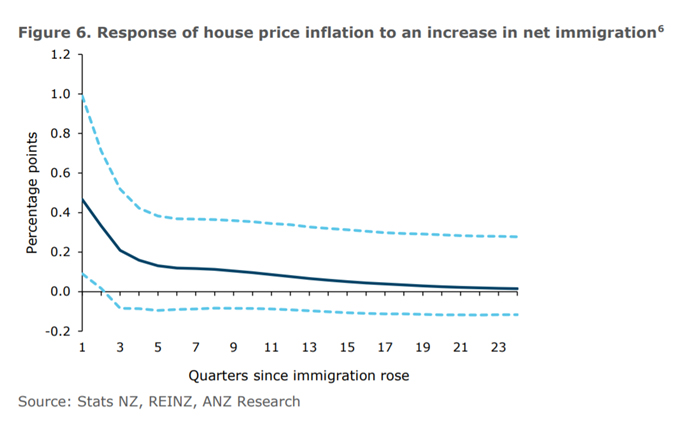

The clearest macroeconomic impact of net immigration for New Zealand is on the housing market, ANZ Research has found. They concluded their report with this statement.

This highlights the importance of addressing the relatively unresponsive nature of housing supply in New Zealand. We simply do not build houses fast enough to keep up with population growth (particularly following periods of strong net immigration, but also more generally), and that’s fundamentally what’s impacting the wellbeing of many Kiwis.

Figure 6 shows the modelled response of house price inflation to a one-off increase in net immigration. Note the dotted lines represent the uncertainty around the estimated responses – indicating the robustness of the results. Source: ANZ Research: How does immigration affect the New Zealand economy

For the last year, the spike in house prices has been due to significant monetary stimulus in response to Covid-19. House price growth in New Zealand is running at the second-fastest rate in the world. The government acted in February 2021 by directing the Reserve Bank to take into account the government’s housing policy in its decision-making, and again in March by changing the tax settings for landlords.

Documents released as part of the May 2021 Budget predicted a sharp house price adjustment is coming. The future is uncertain, so let’s see. No one forecast the Covid-related house price boom, for example, except for a few monetary policy tragics like Jenée Tibshraeny and Bernard Hickey.

The change in property tax settings will have reduced speculative demand, housing construction is relatively high, and due to Covid immigration is low — so supply should catch up with demand at some point in the next few years.

The question is whether supply can have a long-term influence that gradually improves housing affordability or if construction again drops off.

Cullen, whose thorough response showed the depth of his mana and his democratic ethos, was not correct about everything back in 2007.

Firstly, he undervalued the potential for supply side reform to improve affordability, specifically by addressing (1) infrastructure funding, (2) making the planning system more permissive, and (3) undertaking proper spatial planning.

Secondly, Cullen’s view that the housing crisis was cyclical and would pass meant he undervalued the risk unaffordable housing would pose for New Zealand’s economy in the future — wiping out many of the benefits of other reforms, like the 2004 Working for Families package.

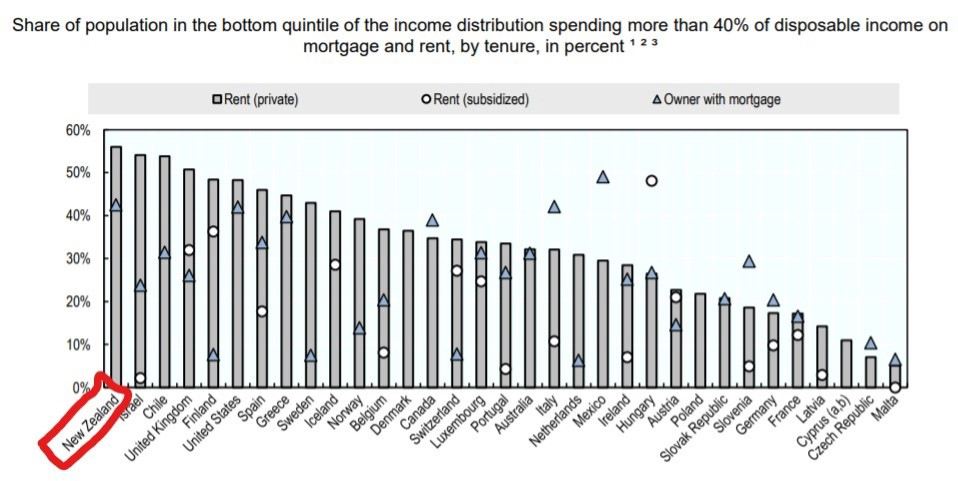

Source OECD -Affordable Housing Database, Figure HC1.2.3.

Thirdly, by not articulating that housing-related inequality is unacceptable to the public and that the New Zealand government has an obligation to ensure all New Zealanders have access to affordable housing. The inequality side of the housing crisis is now better understood by the public following media coverage in 2016 showing homeless families living in cars.

In hindsight, we all have 20/20 vision and I do have sympathy for Cullen’s 2007 housing position. Since then, understanding of the negative effects of unaffordable housing has become much clearer, as detailed in articles like this. I am sure Cullen’s 2021 view on housing has evolved to reflect the events of the last 14 years.

In June 2021, Cullen reflected on his political career in a long interview where he talked about housing at the 53-minute mark.

In the interview, he made it clear he believed the government was correct in 2017 to focus on building more houses (supply), with a particular focus on building for the middle to lower end of the market through state housing or community housing providers. He also thought the government needed more supportive policies covering things like the labour market, building materials, property investment and so forth. The Reserve Bank and the government needed to be better coordinated, Cullen thought. The bank could have lent to the government for its build programme rather than effectively “putting an awful lot of money into asset prices. Which we don’t need — which we simply don’t need.”

In my Rack-Rent series, I advocate for greater centralisation to strategically address affordable housing and ensure it is treated as a human right for all New Zealanders. Part Two of the series recommends a housing tsar would be beneficial.

There are two main advantages for New Zealand taking a centralising approach to solving the housing crisis.

- Housing related-inequality can be tackled without crashing house prices. The government can repeat the state house building policies of the First Labour Government (or a similar version, such as supporting the expansion of the community housing sector using the Austrian model).

- A centralising housing approach could be part of a wider shift towards adopting the East Asian development model so that New Zealand can catch up with nations like Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Back in 2007, I was advocating for greater decentralisation to improve housing-related infrastructure bottlenecks “by replacing local councils with a smaller number of regional councils and assigning a percentage of income tax (at the local level) to these councils”.

How do I reconcile my 2007 position with my more recent centralisation view?

Basically, I am a pragmatist. I agree with Deng Xiaoping, who said: “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is white or black, as long as it catches mice.”

There are multiple options for addressing the housing crisis.

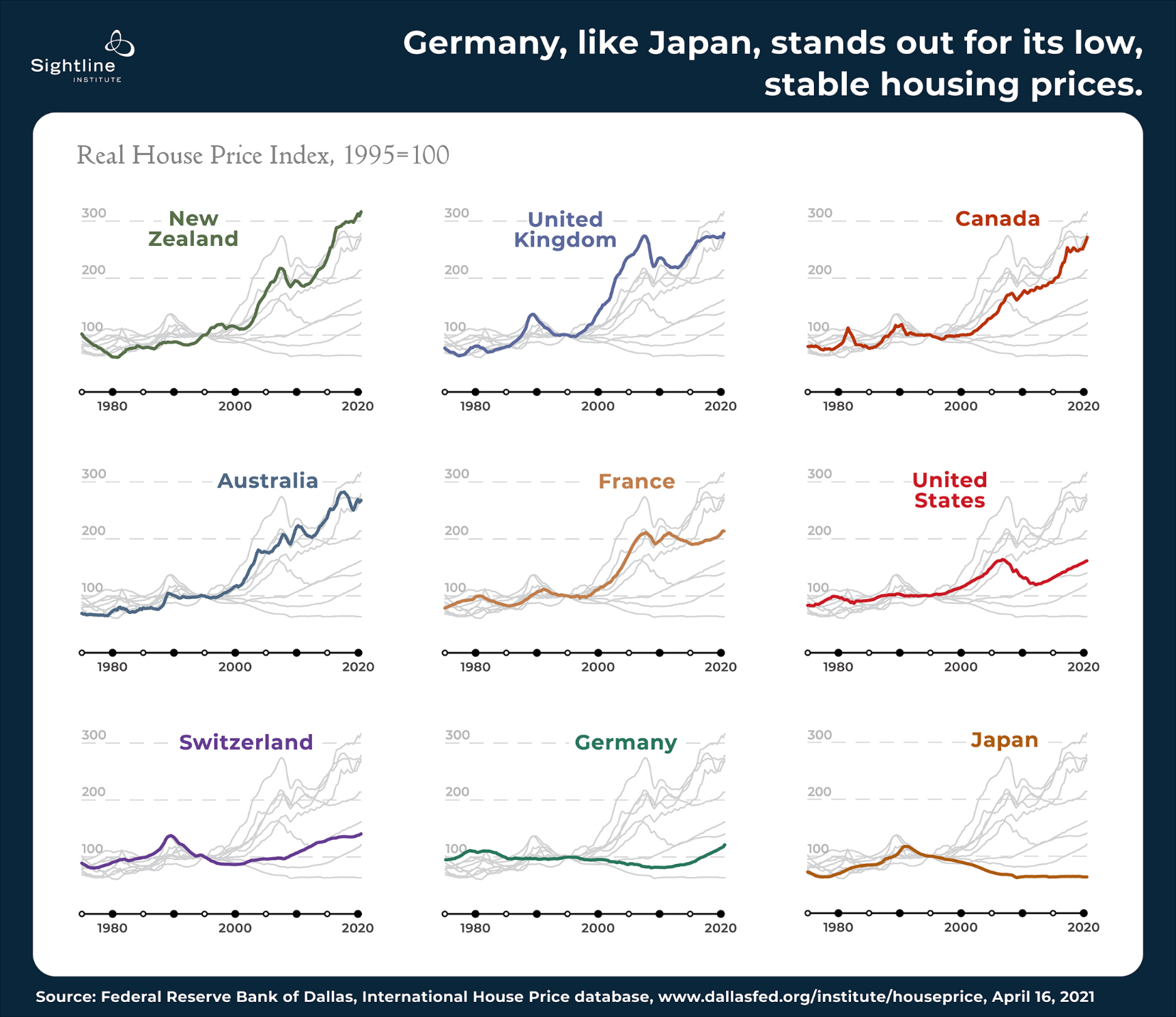

Source — YES, OTHER COUNTRIES DO HOUSING BETTER, CASE 2: GERMANY

The two countries with the most successful and stable housing markets over the last 40 years — Germany and Japan — have taken quite different approaches along the centralisation spectrum to achieve housing success.

Alan Durning from the US Sightline Institute describes the difference as:

Japan’s lesson, as I previously wrote, is that pushing power to higher levels of government is a tonic for housing. It counteracts NIMBY obstructionism. Germany’s lesson is that decentralized control can be fine, as long as local authorities have strong incentives to welcome homebuilding…

Local German officials, like local leaders everywhere, seek bigger budgets to provide more and better services to their constituents. What’s different about Germany is that the way to get bigger budgets is to increase local populations. And, as Professor Buettner says, “Ultimately, to get people, municipalities will need to support housing.”

Professor Robin Hambleton from the University of the West of England describes how small German cities like Freiburg have made bold moves to address housing affordability and the climate emergency. He states the extreme centralisation of the UK rules out these sort of imaginative initiatives. New Zealand has a similar degree of centralisation.

The German system of incentives is the opposite of “fiscal zoning” — the practice of zoning land in ways to maximize local government income and minimize its costs.

In the US, fiscal zoning has meant in places that use sales taxes as a local revenue source, such as Washington State, more land for shopping centers is zoned. In places where residential property taxes are capped, such as California, they zone less land for homes and more for offices. In affluent suburbs, they often zone land for standalone housing on large lots, thereby excluding low-income people.

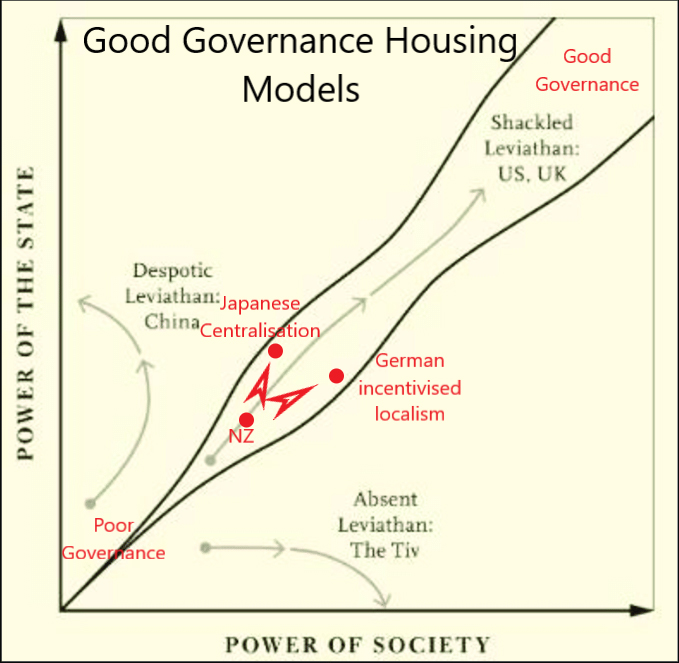

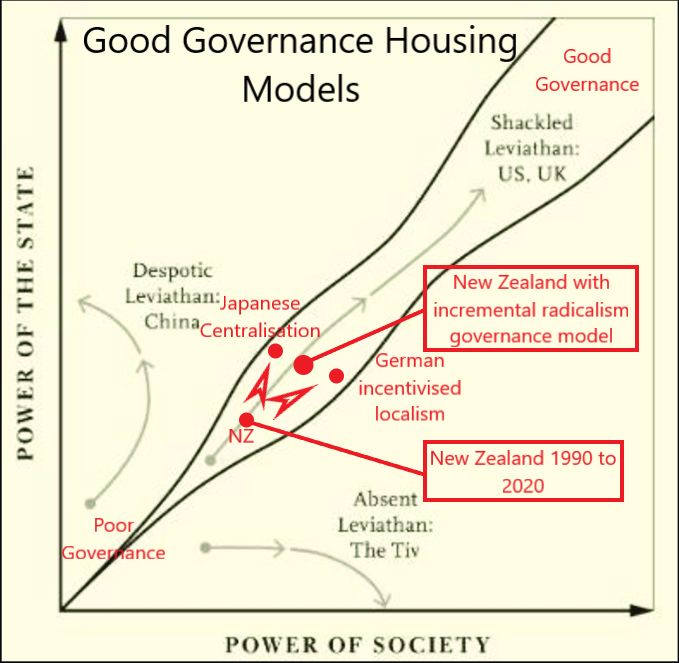

From Figure 1 in Book —” The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty”. Which is about the path to a good governance society being a balanced race between the power of the people and the power of the state. Title and red notations have been added by Brendon Harre.

Ultimately, what is needed is better government that can provide the conditions for housing markets to be successful. Good governments — like those in Japan and Germany — provide permissive house building regulations with low transaction costs (entities such as Vienna’s social housing agency have provided a similar function). Good governments also deliver the required public infrastructure that markets cannot provide.

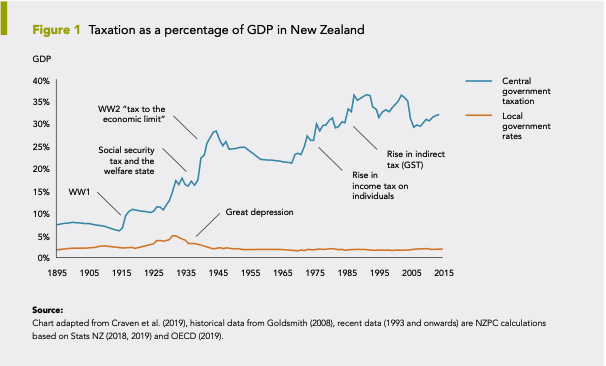

Source —The Council-Government Divide

The nature of local government in New Zealand means its revenue source is constrained by politics. Local government rates revenue has not risen as a percentage of GDP since the late 1800s. A recent Productivity Commission report noted councils faced pressure from homeowners to keep rates low which prevented necessary investment in housing-related infrastructure. Local government in New Zealand is similar to the California situation: politics has imposed a revenue cap, meaning there is an infrastructure bottleneck and permissive planning rules are not incentivised.

While there is a distrustful relationship between central and local government, this situation will only continue. One kernel of distrust is that local government accuses central government of making it impotent and central government does not respond because it believes local government is incompetent.

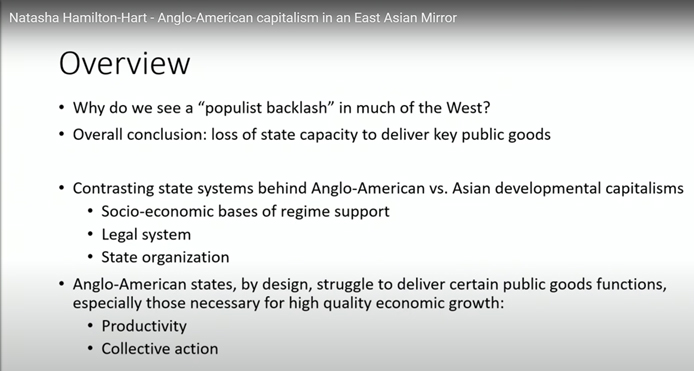

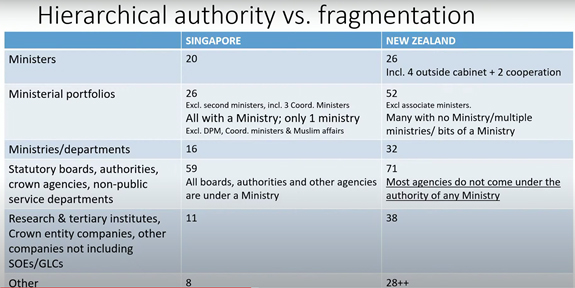

Source- Professor Natasha Hamilton-Hart talk on “Anglo-American capitalism in an East Asian Mirror”

Despite knowing the consequences of a lack of local government incentives, more recently I have been advocating for more centralisation to address the housing crisis. This is because the Japanese centralisation model (or more generally the East Asian development model) is a genuine success. The reality in New Zealand, is that governments from both sides of the political spectrum have lacked the will to empower local government, something Cullen accurately predicted in 2007.

However, the current Labour government will not centralise housing-related public service delivery like the first Labour government did. By 1940, state land development programmes accounted for 45 per cent of all housing construction in New Zealand. This required a Ministry of Works and a huge government state house build programme. In comparison, the current government house building programme makes up only about 10 per cent of total residential construction (Kainga Ora is building less than 4,000 of the roughly 40,000 houses being constructed each year).

After its landslide victory in the 2020 election, the government had an opportunity to implement the first Labour government’s housing model. For the first time since MMP was introduced, one party had majority control. The barrier to that course of action is not party politics —because currently there is no effective opposition — the problem is the fragmented public service.

Source- partial slide from Professor Natasha Hamilton-Hart talk on “Anglo-American capitalism in an East Asian Mirror”

Even if there is the political will to reform governance in the following areas:

- More centralised housing related infrastructure provision.

- A national set of permissive planning regulations.

- A more coordinated set of actions between government and the private sector (to build the vegetarian city model – which will be the topic of my next article).

The fragmented state of the public service means New Zealand would still struggle to implement these reforms.

What happens next?

If radical change is not possible by switching to the German model — incentivised localism — or the Japanese model — centralisation — does that mean New Zealand’s housing crisis is an insurmountable problem? Not necessarily.

New Zealand might become more aware of its disempowered and fragmented governance systems and therefore make greater efforts to ensure collaboration and coordination occurs. Constructive engagement should be valued, and finger-pointing and blame-shifting frowned upon.

Incremental reform that sits between the Japanese and German models is possible. New Zealand could even create its own ‘incremental radicalism’ governance model (note the term ‘incremental radicalism’ is discussed at the end of this talk by veteran political analyst Colin James).

The government is currently working on a bunch of reforms that could improve housing governance. Individually, each reform will only have a minor incremental effect, but collectively they may add up to something more radical.

Examples of these reforms are:

The National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD). This is the government’s first attempt at directing councils to implement a more permissive planning system; for instance, by raising height limits around rapid transit and removing car parking minimum requirements. Councils are currently in the process of implementing the NPS-UD (as seen by the recent housing debate in Wellington). There are concerns, however, that Auckland Council is planning for unaffordability.

The planned replacement of the Resource Management Act over the next few years will give the government more opportunities to incrementally implement a more permissive planning system, which may be needed if local government push back against the spirit of the reforms.

Clearer national direction will be provided under the Natural and Built Environment Act (NBA), and “the new National Planning Framework (NPF) will provide strategic and regulatory direction from central government on implementing the new system. This will be much more comprehensive and integrated than the RMA required” (42).

The government has created a $3.8 billion infrastructure fund that local government can access. However, commentators have criticised the size of the fund, saying it is insufficient compared to the size of the infrastructure deficit.

Of the $3.8b, Housing Minister Megan Woods announced $1b has been set aside to create a contestable housing infrastructure fund. Funding will be available for projects that provide drinking water, waste water, sewage, roading, and flood management that enable new houses to be built. To qualify for funding, infrastructure projects need to support the building of a relatively large number of houses, at least 200 homes in larger cities, 100 homes in smaller cities and 30 homes in towns.

The $3.8b fund is a step in the direction of incentivising localism that could, over time, be improved into a more formal structure. However, the fragmented nature of the governance system in New Zealand means, for every step towards localism, there seem to be barriers pulling the country further away.

For instance, most New Zealanders are unaware that fuel tax and road user charges do not pay for the full cost of the road network. Ratepayers significantly subsidise roads and recently the New Zealand Transport Agency (Waka Kotahi) told Councils to expect $420m less for local roads than originally indicated, forcing councils to cut spending on cycling infrastructure, public transport and local roads in hastily rejigged budgets for the next three years. Auckland Council, for example, has delayed its Eastern Busway for two years following the NZTA funding cut.

The Local Government Minister wants to centralise three waters provision (fresh, sewer and storm water) in New Zealand. I can understand the attractiveness of a Scottish Water type entity (or four such entities) using volumetric charging to provide fresh and sewer water services (although a single water standard is problematic given the 150 year history of using non-treated water from capped artesian water sources in places like Christchurch).

Many local governments historically have favoured lower property taxes over expenditure on three waters infrastructure. In the short term, this has been a politically successful tactic but in the long term it has led to water delivery failure. Hence the desire for reform.

Regarding storm water provision, I have concerns that an unelected water entity will lack the mandate needed to make required land-use changes to manage flood protection. Christchurch, for instance, invested $120m to create large storm water basins and other drainage schemes that prevented the city flooding during its recent heavy rain event. Christchurch City Council has also put more effort into gaining an accurate picture of sea level rise and its implications than the Ministry of the Environment has. After significant rain events, many farming areas ask for drainage scheme protection, some of which will be beneficial and some highly contentious as there has been a systematic effort to strangle rivers into narrow drainage corridors. A distant, unelected water entity will struggle to navigate these local issues.

It is likely that New Zealand’s busiest cities will be allowed to congestion charge the overloaded parts of the road network. Congestion charging can provide many benefits, including improving the use of existing infrastructure, informing better transport planning by providing credible signals of effective demand, and requiring people living in new suburbs to internalise the congestion costs that they impose on other transport users.

In 2020 the Urban Development Act was passed. This created a Kainga Ora-run urban development authority following on from the Hobsonville Land Company, an entity which was wholly-owned by Housing New Zealand. The original concept of developing Hobsonville dates back to the Clark/Cullen-era, although the scheme was implemented by the Key government. The National-led government made significant changes, like removing the 15% state housing requirement. No new housing development areas have been announced following the passing of the Urban Development legislation in 2020. Going forward, the current or next housing minister may be more enthusiastic about using this housing supply tool.

Among other beneficial changes, the replacement of the 30-year-old Resource Management Act with a Strategic Planning Act and a National and Built Environment Act, could allow New Zealand to undertake proper regional spatial planning. The existing 100-plus RMA council planning documents will be reduced to about 14.

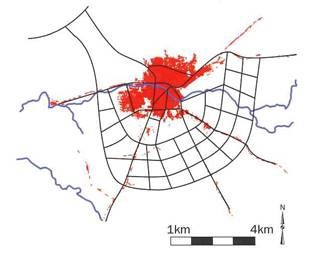

New Zealand cities and regions could undertake initiatives like New York’s 1811 Commissioner’s Plan that designated a road grid for Manhattan Island which was later able to accommodate the subway network. This spatial planning work was a critical step that allowed New York to become the largest and densest city in the US, while having a lower rate of transport-related CO2 emissions than Auckland (on a per capita basis).

Spatial planning has been successfully done around the world, including Barcelona’s 1859 Cerdà plan. Ontario’s late-1800s designation of north-south and east-west paper roads throughout the province meant the roads were later used to provide a grid system of frequent public transport services for Toronto. Copenhagen’s 1947 Finger Plan guided development into multi-modal transport corridors and protected the ‘green wedges’ between corridors.

New Zealand’s failure to spatially plan its urban growth areas is shown by the fact that only 9.5% of homes built in 2019/20 had access to frequent public transport services, according to the Ministry of Transport (quote from Page 22 of this discussion document).

The direct impact of poor spatial planning is:

- Vast cost escalation. Infrastructure Australia found billions of dollars of cost escalation because the corridors protected in the 1950s, 60s and 70s were built out in the 80s, 90s and 00s, and now they have run out. New Zealand is in the same situation.

- Inability to build transport projects to add transport capacity, provide congestion free travel alternatives, and to reduce CO2 emissions because there is not enough room on public right-of-ways. For instance, arterial roads in New Zealand are frequently too narrow to fit rapid transit and active mode infrastructure.

- This leads to housing supply constraints that cause shortages, unaffordable homes, and overcrowding.

- In turn, there is less urban development from the infrastructure projects that are built, reducing their uptake and benefits.

The wider societal impacts are:

- Increasing inequality (e.g., a landed gentry and a renting class).

- Lost agglomeration economies and lower wages because of congestion and disconnected labour markets.

- Reduced flexibility to repurpose transport systems to reduce emissions.

- Increased risk of economic depression from overinflated urban land prices.

- High infrastructure costs requiring higher taxes and lower value for money.

Spatial planning solution:

- Plan, protect, and pay to acquire land for corridors and a regional hierarchy of public open spaces so that cities have the capacity, if needed, to double or treble in population size over an extended 50-year time period, through both urban intensification and competitive urban expansion.

- The corridors should be connected (i.e., grid-like), perhaps spaced about a km apart and 30 metres wide each.

Time will tell if these sorts of incremental reforms can be implemented ‘radically’ enough or whether New Zealand needs to move past its current practices to create an entirely new system better suited to tackling the housing crisis, climate emergency, inequality, and productivity obstacles the country faces.

Dear Mr Harre

Thank you for your email of 19 May 2007 forwarding your article on housing affordability and supply. I appreciate receiving your views.

Your main thesis is that house price affordability is at low levels due to demand for housing out-stripping supply. I agree that supply limitations are partly responsible for the increase in house prices; although I also consider that there are a number of other factors that are contributing to significant house price inflation. In particular, growth in borrowing capacity is likely to be the biggest driver of house price increases. The combination of low interest rates (by historic standards), banks’ access to cheap foreign capital, and growth in income means the households can afford to borrow more. In the last seven years, almost 320,000 additional people entered work, and wages have increased by around 13 percent (after taking account of inflation). Job security has given people the confidence to borrow more. I would also note that the influence of supply on prices is not straightforward, since the supply of new dwellings has expanded rapidly in most areas, including Auckland.

The link between house price and macroeconomic effects is strong. The Reserve Bank, in its role of controlling inflation, considers the housing market to be an important transmission mechanism for monetary policy since such a large part of the population is affected by changes in mortgage rates. The response of monetary policy, by way of rises in the OCR, is intended to dampen inflationary pressures, but because so many mortgages are on fixed rates monetary policy has taken longer to work.

Other influences on house price inflation include immigration, the role played by the investment property market and growing demand for larger and higher quality housing.

The solution you propose to solve affordability issues is to force, through legislative change, regional authorities to balance local demand and supply for land by setting a house price inflation target which would be met through greater land release. Aside from any other considerations, I would expect such a target to be unachievable through the supply side alone. In many parts of the market land is finite so any change in demand in those areas would presumably result in increased prices.

Nevertheless, I acknowledge there is room to influence overall prices by increasing supply, either through new developments or infill developments. There are elements of the government’s housing strategy focused on achieving increased supply. You are probably already familiar with this government’s substantive review of housing policy, released in 2005 as the document “Building the Future: The New Zealand Housing Strategy”. Although house prices have continued to rise since this document was published, the findings and recommendations are still relevant. If you are not familiar with “The New Zealand Housing Strategy”, you can view it from the link (no longer active) if you have access to the internet. The first chapter of the report is focused on responses to supply limitations.

To meet our goals of adequate housing for all New Zealanders, government housing policy needs to incorporate a range of assistance, rather than just helping first home buyers. For example, officials have been working on a range of planning tools that could be used by local government to increase the supply of affordable housing in communities where it is scarce.

You suggest a method of funding the infrastructure needs of increased development by replacing local councils with a smaller number of regional councils and assigning a percentage of income tax (at the local level) to these councils. As you note, your proposals require a fundamental change in our system of government. It goes without saying that any change of this magnitude would first require detailed assessment of the risks and cost at all levels, and subsequently would need cross-party support. Even if there was a political will for such change (and this is very doubtful) this process would not happen quickly. Given that fluctuations in house prices and housing affordability are inherent characteristics of housing markets, it is quite possible that the present housing affordability crisis could be over before any changes were implemented. This current cycle is exceptional — house prices have risen by more than at any time in the last 30 years — but forecasts by the Treasury and the Reserve Bank suggest that the current rates of price increase will not be sustained.

I hope my comments have helped to explain the government’s position. Thank you again for forwarding your article.

Yours sincerely

Hon Dr Michael Cullen

Minister of Finance

This is a repost of an article here. It is here with permission.

58 Comments

It's not New Zealand's failure. It's a failure of New Zealand's leadership (specific people) and government systems

I'm not so sure. I think the average Kiwi is prone to being a pathetic NIMBY on all of these issues. We can be quite egalitarian about some things, but where property is concerned that all goes out the window.

Governments in democratic countries are usually a pretty good mirror of the people.

Germany 1932, the Nazis were the most popular party in Germany. Voted in under a democratic system. Not sure your average German 'deserved' Adolf + co.

What's been disappointing to me is that the decline in housing affordability has not been met with an increase in urgency to increase supply. Far from being treated as a basic human right this is continuing to treated as a very peripheral issue. Policy is badly lagging the real economy and policy makers are too slow to react to economic changes.

A housing shortage should actually be a huge opportunity for New Zealand to create employment and productivity growth.

Do you see the irony? NZ sees productivity and output as 'wealth destruction'.

hear hear, well said.

One problem is that migration settings are set by central government, yet local governments have to supply most of the extra infrastructure needed.

Perhaps central government should reimburse local councils (say) $200,000 for each migrant that moved into their area.

Perhaps the businesses screaming out that they can't find the local labour need to pay some of that money as well.

I work for a fairly large company, one that could easily train people in areas with skill shortages, but do they do it?

Nope, import another punter from offshore and pay them well below the market rate.

Some of the new imports have average skills like project management.

How they hell are skills that are a dime a dozen getting through the gates.

Yes, I agree. The cost should be borne by the migrants themselves or the people profiting from them, not the hapless taxpayer or ratepayer.

Admire your persistence Brendon but I think you are wasting your time. Neither major party has any genuine interest in addressing the issue. C'est la vie.

The examples of Japan, S'pore, and Korea are good, but I think what Brendon fails to note is that all 3 countries up to the 70s were relatively poor at the h'hold and individual level. The establishment of housing infrastructure was absolutely necessary in these countries' long-term plans. Part of that is related to Confucian values that puts emphasis on the whole (the group) over the individual. NZ society, whether it likes to think so or not, seems to based more on faux 'class based' values, a kind of aspirational suburban existence where one has a stake to be defended or to claim a better kingdom (a kind of social climbing ethos). Ultimately, the lack of any long-term vision will fail NZ. Now, some may some that Japan is already a failed state despite the progress it's made. I disagree. Japan is self sufficient on the whole and has probably the world's best infrastructure.

Similarly, Germany had a long-term vision after WWII. They also wanted to bring their people out of poverty. Culturally and economically, Germany is highly productive compared to the likes of NZ. They understand that this is not possible without some level of stability and order. Housing is a pillar of this.

I agree, a long term plan is required and as importantly an emphasis on the collective good. But if NZ was ever to do this would now not be the time? Social cohesion around CV19 and consecutive comprehensive wins for the labour party mean if not now then when?

May I suggest that lack of population growth has been a big factor in Germany and Japan.

What are you talking about? A big factor in 'what'? Of any European country, Germany has accepted immigrants far more than others. Japan has a declining population, but that is not the point. The housing infrastructure of Japan started in the 1960s.

Hey, calm down :) Passive aggressive!

Yes there has been a lot of refugee intake into Germany, but beyond that population growth has not been significant. Birth rates have been very low in Germany for a long time

Refugees hardly create a strong demand for private sector housing.

Prices increased significantly in Japan throughout the 1970s and 1980s, with rapid economic growth and moderate population growth.

Then the bubble burst, and population has also been declining over the past 30 years.

Or you don't think the rate of population growth has much significance on housing? If so, I strongly disagree.

I tend to think JC is on to something; unless if you could even mildly prove the significance between population growth and house prices.

Umm, it's in the graph above plainly. In the graph that shows the separation from the amount of immigration and houses consented as an average.

Is it just coincidence that the countries with the highest population growth have the most unaffordable housing?

I would suggest not.

But they don't. If you take for example Texas (as a country economy) then they have had high immigration and low house prices.

Growth of any type only becomes a factor if supply is less than whatever the growth rate is.

Or you don't think the rate of population growth has much significance on housing?

Brendon's article is about housing supply and infrastructure using examples of how other countries have dealt with it, including Germany and Japan.

It's not another inane 'I reckon' to justify or explain the NZ property price bubble around popn growth.

He has provided valid reasons, which I don't dispute, as to why housing is more affordable in Germany and Japan.

He didn't mention lack of population growth. I maintain that is a significant factor.

I don't see what the issue is, you seem to have got your back up on this for some strange reason.

Have a look at population graphs for Germany and Japan over the past 30 years.

Have a look at population graphs for Germany and Japan over the past 30 years

Look at the population growth of Osaka and Tokyo from the 50s (https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/tokyo-population). The growth was far more rapid than recent population growth of NZ. That is why Japan needed to develop its housing infrastructure.

I think any consideration of Japan is a bit irrelevant anyway though. There, they consider their houses disposable. They're often torn down and rebuilt every 20-30 years. They construct them cheaply and expect them not to last.

Clearly a totally different situation than NZ, or indeed most developed countries.

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/nov/16/japan-reusable-housing-r…

. There, they consider their houses disposable. They're often torn down and rebuilt every 20-30 years. They construct them cheaply and expect them not to last.

Urban myth. The quality and longevity of Japanese housing construction is now second to none. Quote from Sekisui House whose houses have 30-year warranties:

For structural frames and rainwater-proofing components, we offer a 30-year warranty, which provides an additional 20 years to the 10-year liability period required under the law promoting housing quality. In addition, all other components are under warranty for a specified period of time. Even after the warranty period has expired, homeowners can take advantage of our U-trus system to extend warranties in 10-year intervals.

https://www.sekisuihouse.co.jp/library/english/company/sustainable/p.41…

One company choosing to offer 30 year warranties on houses they build now says nothing about what generally happens in a country of 125M people and their existing housing stock.

I’ve spent a reasonable amount of time in Japan; I’d say their housing is lightweight but very well-engineered, like many Japanese products. I’d choose a Japanese-manufactured house over a classic Kiwi one any day. Their climatic and seismological conditions are very comparable too.

Still doesn't refute anything about most Japanese houses expecting to be torn down within 30 years.

I am picking the stuff being built here at the moment will be lucky to be still in good shape at 30years as well. All that polystyrene!!!

I agree, NZ was a world leader in immigration getting up to 2% new people in each year. This has had a specific a provable link to house price increases as is seen in the graph above that illustrates houses consented to immigration.

The link is weak and insignificant.

Says who? Anz economists stated a significant link between immigration and house prices just a few days ago.

Yip, going so far as to say that pre-COVID-19 immigration levels would result in prices doubling from current levels within 5 years. That's hardly weak or insignificant.

That's an exaggeration. The national median house prices only increased 37% between 2015 and 2019- far from the 100% you claimed.

In the last 13 months, long term net migration is down 95% and national median house prices is up 21%.

If anything, this disprove a direct causal link between net migration and house prices.

I'm in favour of net immigration does not have a direct relationship with house prices.

Re-read what I said, because I didn't claim they had gone up by 100% in 5 years like you seem to think.

Exactly.

Have you even seen their model?

Let me suggest to you that the clock on your wall has a strong link to rising house prices. The more clockwise turns it makes, the higher the house prices go.

he Western concept of a residence as a stable and secure long-term investment—more tree than flower—that will gradually increase in value over time directly opposes the Japanese view, which sees a house as a temporary structure that expires with its owner. A Japanese building is a short-lived consumer product, not so different from a car or an iPhone, that undergoes a period of fixed-term depreciation, set by the government at 22 years, after which it’s considered fit for the scrap heap. If an Englishman’s—or Westener’s—home is his castle, a Japanese one is a worthless piece of single-use plastic.

Rubbish. As I mentioned above, Sekisui House builds homes with 30-year warranties. Good luck getting that in Nu Zillun'.

https://www.sekisuihouse.co.jp/library/english/company/sustainable/p.41…

Picking one company building *new* houses to a certain standard, as if it reflects the existing housing stock or actions of 125m people in the country is rather foolish.

Also the point is not "they are built shoddily so must be torn down within 30 years" it's "they choose to build them cheaply and expect them to be torn down within 30 years". They're very different concepts. Just like some people expect to replace their iPhone every 18 months, even if the old one is still perfectly good.

https://freakonomics.com/podcast/why-are-japanese-homes-disposable-a-ne…

https://robbreport.com/shelter/home-design/japanese-homes-are-ephemeral…

The vast majority of these new builds replace existing new-ish dwellings. The Japanese government dictates the “useful life” of a wooden house (by far the most common building material) to be 22 years, so it officially depreciates over that period according to a schedule set by the National Tax Agency. Even if buyers wanted to (which they don’t), they would struggle to purchase an older property, as banks will not lend against a worthless asset. “The banks and real-estate agents cannot value the building beyond book value,” says Toshiko Kinoshita, a Tokyo architectural historian.

If you want to continue to hold up the actions of 1 building company as if it somehow invalidates everything else that has been written about what happens with houses in Japan, go ahead, but I'm not going to engage with it any further.

Yes. Having lived in Japan for several years in the 1990s and having Japanese family, I can attest to that.

Picking one company building *new* houses to a certain standard...

Sekiusi House and Daiwa House are the biggest builders of homes in Japan, approx 80% of new homes. Sekisui is the one of the world's leading innovators of housing and performance materials in the world.

Your claims are nonsense. Most of the shoddy construction happened during Japan's rapid growth and when the construction industry was unregulated and controlled to some extent by the Yakuza. Times have changed.

My sister in law's townhouse in Japan is custom architect designed and built. They see it as having a 25-30 year life.

Good for her. If she bought a house from Sekisui, it would probably last her a lifetime.

At least the structural parts of a new New Zealand house have to have at least a 50 year life, according to the Building Act.

Enjoyed reading this - refreshing depth!

'Local government in New Zealand is similar to the California situation: politics has imposed a revenue cap, meaning there is an infrastructure bottleneck and permissive planning rules are not incentivised' - Truth!

The fundamental issue here is that it is not currently economically viable for any company to build a decent home and rent it out at an affordable rent - and it this type of housing that is desperately needed. So, Govt needs to provide a per unit subsidy for affordable rental housing that covers the cost of supporting infrastructure and (probably) some of the build costs. The $3.8bn is a start - but it will only enable support, what, 20,000 to 30,000 units?

Good to see the supply chain issues called out though - we have a housing crisis and at least 80% of our skilled labour and materials are being used to build houses for rich people.

What grates my cheese is successive Governments have screwed the pooch on housing, and then the bloody tax payer has to bail them out by meeting the costs with social housing, accommodation grants and "working for families.' Anyone feel like punching a politician? Editor-this is posed as a question, not to instigate violence. No need for censure :-)

Yeah, except a lot of taxpayers have also got wealthy from this situation, and wouldn’t like the outcome of Gov’t competence , which would be falling prices.

The irony is that "the bloody taxpayer" elects these successive governments.

Auckland has a very detailed spatial plan for future growth with a strictly enforced RUB directing new development. The Auckland plan is that 70% of future urban land must occur in places where there can be little public transport effectiveness. Our urban planners have decided that our sprawl must be massive, expensive, but above all disconnected.

Jacinda Ardern ran in 2017 on a policy of removing the RUB around Auckland and she won. Only if her government had implemented that policy would Auckland lack spatial planning. Ironically if she did and chaotic sprawl resulted, our populations access to effective transport would be greater than it is under the Auckland Plan - because without spatial planning we would be able to build in much more compact areas.

Great article desperately grappling with the main issue in NZ.

Wow, doesn't Cullen's letter from 2007 document a fail of epic proportions?:

This current cycle is exceptional — house prices have risen by more than at any time in the last 30 years — but forecasts by the Treasury and the Reserve Bank suggest that the current rates of price increase will not be sustained.

"New Zealand’s rack-rent housing crisis: Where to now?"

Where to now......wherever Mr Orr and Jacinda Arden wish.....to the moon...

Dr Cullen gave you the correct answer in 2007... "In particular, growth in borrowing capacity is likely to be the biggest driver of house price increases. "

What he forgot (?) to add was it was by design.

While we have failed to build sufficient public housing the past 20 years our general construction numbers have been sufficient even with the high levels of immigration (as demonstrated in the OECD report you linked) but the problem has been the allocation of that housing....as the same report notes we have approx 7% of our housing stock empty...140,000 properties.

The gov are singing their own praises increasing the public housing stock by 18,000 over 5 odd years when they know that they need to at least increase that by a factor of 2.45 to return us to the ratio of the 1980s....but that potentially risks a downward spiral in property prices and therefore credit growth

Given credit growth has long replaced economic output as the source of growth an affordable housing market will be sacrificed on that alter for as long as possible.

However with interest rates and debt where they are the cliff approaches

Speaking of Germany as good example for housing affordability: house prices in centres such as Hamburg, Berlin, Cologne and Munich have nearly doubled since 2016 and rents went up almost as much.

*****Supply limitation*****Number of other factors*****No silver bullet*****growth in borrowing capacity

Same carap different governments, always having a same template answer, no change whether it's 2008, 2021 or 240. I believe we have to accept the reality as it's kind of disability which cannot be fixed. In return we only get lip job from different parties want to be in power to rule our country.

In summary, our political parties can only govern with some form of effectiveness when we are in a crisis when they can adopt a 'war' agenda and the population is willing to hand over personal freedoms so the Govt. can govern by dictate.

This by default means micromanagement of our daily lives, ie they start telling us what we have to do on a daily basis.

This leads to a self-fulfilling prophesy by Govt. to create crises to give them that authority, as luck would have it for Labour, a crisis given to them ie Covid.

I agree with Brendon, that Govts. The main role should be to set out the basis spatial plan, ie macro-management, but where we differ is that I would then remove restrictions within the spatial plan and let the market decide when the 'gaps' are filled in.

This is the Texas model which has resulted in true affordable and stable housing.

But for this to happen Govt. would have to step back from micromanagement to have the future foresight to set up a macromanagement spatial plan.

Good morning Brendon. Its awesome you are a passionate campaigner from way back, fighting for people's basic needs. You have at least been doing this for the last 14 years since 2007 and what a period it has been. Extraordinary claims and promises have been made by politicians who have come and gone, and some who have not yet gone, yet where has it left us as a country.. I leave you to answer that... but here is a word of advice, do not believe any of the rhetoric and hot-air promises the pollies make between now and the next election or ever. The bigger the promise, the more fake it is.

As a landlord the title Rack Rent Crisis tells me quite a bit about the coming article.

I got as far as him saying centralisation is needed and quoting Den Zhaoping.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.