By Christian Hawkesby

This week's United States elections are set to bring to a head two factors that will need urgently addressing by the incoming administration, whether it be Democrat or Republican.

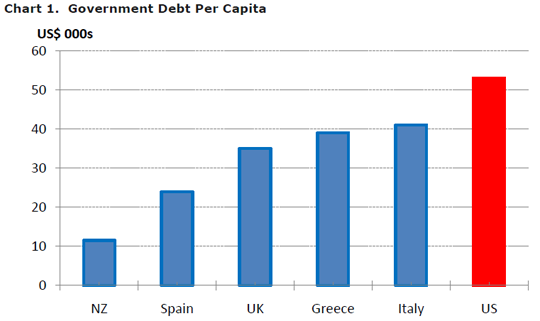

First, the level of US fiscal debt is unsustainably high, even compared with European countries facing sovereign debt crises - as the accompanying chart 1 demonstrates. Without some combination of spending cuts or increases in tax revenues, the situation can only worsen.

Second, almost every stimulus package instigated by the Bush or Obama administrations is due to expire in January 2013 unless the terms of these packages are renegotiated. If triggered, the harsh spending cuts and tax increases of this so-called “fiscal cliff” have the ability to propel the US economy back into recession.

We sum up the situation facing the US as follows:

- After the election the so-called US fiscal cliff will be a key focus of markets.

- Most fiscal stimulus measures enacted since the GFC mature in January next year. These will need to be renegotiated, in an environment where there is likely to be a division of power between the White House, Senate, and Congress.

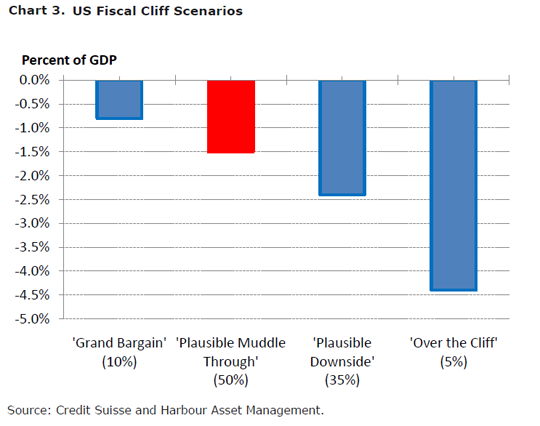

- There is significant uncertainty about the outcome of these negotiations, with the size of the resulting fiscal headwinds ranging from 0.8 to 4.4 % of GDP.

- Markets are worried that there is a small chance that a breakdown in talks would take the US economy "over the cliff‟. We put this chance at 5%.

- We believe that a "muddle through" compromise is the most likely outcome. Furthermore, unlike the failed US debt ceiling negotiations in 2011, the backdrop in recent months has shown improving US economic data and a more stable environment in Europe.

- A "grand bargain" between the parties would be a surprise to markets. We put this chance at 10%.

A well-flagged challenge

The challenge facing US politicians has been well flagged. Back in July, in his semi-annual testimony to Congress, US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke summed the situation up well, when he said:

“U.S. fiscal policies are on an unsustainable path, and the development of a credible medium-term plan for controlling deficits should be a high priority. At the same time, fiscal decisions should take into account the fragility of the recovery. That recovery could be endangered by the confluence of tax increases and spending reductions that will take effect early next year if no legislative action is taken… The most effective way that the Congress could help to support the economy right now would be to work to address the nation's fiscal challenges in a way that takes into account both the need for long-run sustainability and the fragility of the recovery."

The task of the new administration will be complicated by the fact that it is highly unlikely that one political party will have control of the White House, Senate and Congress. Any solution will require political co-operation and bi-partisan support.

Anticipating the need for cross party support to build a credible plan for deficit reduction, President Barack Obama set up the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility in February 2010. This is chaired by Republican Alan Simpson and Democrat Erskine Bowles. In the recent Presidential election debates, both Obama and his opponent Mitt Romney claimed they would follow the broad principles of the so-called Simpson-Bowles Plan, while still discrediting the intentions of their opponent.

Regardless of whether the election is won by Obama or Romney, uncertainty about the US fiscal cliff is unlikely to be resolved quickly. After the election, the next session of Congress will be a so-called “lame duck” session, before new representatives are sworn in and departed representatives leave in the New Year.

Both Obama and Romney will be looking for opportunities to delay elements of the fiscal cliff into early 2013 and beyond. In the meantime, markets will be eagerly looking for a credible plan to provide confidence that there is a timetable for the US fiscal problem to be addressed.

A steep cliff

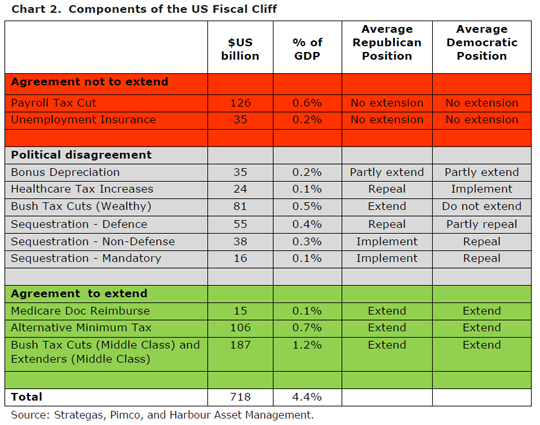

Assessing the potential steepness of the US fiscal cliff requires an understanding of first, the size of each of the stimulus measures due to end in January, measured as a percentage of GDP, and second, the likelihood for political compromise to agree how each of the stimulus measures are dealt with after the election.

Chart 2 groups the components of the fiscal cliff into three categories. Highlighted in red are potential areas of agreement not to extend measures. Areas of agreement to extend measures are in green, while the grey areas are those currently lacking political consensus. These help you understand how the best and worst cases come about.

The "best case" is that they agree not to extend the first category (i.e. payroll tax cut and unemployment insurance), consistent with the average political positions of Democrats and Republicans. That would represent a 0.8% drag on GDP growth. This represents a "grand bargain", as it requires agreement on all the grey areas of current disagreement. We put a 10% chance on this outcome.

The "worst case" is that they let all the programmes go "over the cliff", including the third category - which at the moment they seem to agree on extending (i.e. Medicare, and the Bush Tax Cuts to the Middle Class). This is highly unlikely, given neither political party wants this scenario. It would only be triggered by a complete breakdown in post election talks. In effect, it requires politicians to drive over the cliff to spite their political opposition sitting in the passenger seats.

The over the cliff scenario represents a 4.4% drag on GDP, and would be certain to put the US economy back in recession. We put a 5% chance on this outcome. The middle category captures all those programmes where there is some dispute about whether to implement, repeal, extend or partly extend. It is within this grey area that political pundits and economists are estimating scenarios for a "plausible muddle through" and "plausible downside" scenarios. As an example, Credit Suisse estimates these as a 1.5% and 2.5% drag on GDP respectively. Given the work behind the Simpson-Bowles Plan, we believe that there is a 50% chance of a plausible muddle through and a 35% chance of a plausible downside. These various fiscal cliff scenarios are highlighted in chart 3.

It is important to remember that these estimates of the headwinds from the US fiscal cliff are only one element that will determine overall GDP growth in the US next year.

Recent experience in Europe illustrates that there can be strong multiplier effects, with austerity measures causing even greater contractions in GDP due to the knock-on effects to business and consumer confidence. Against that, there is evidence that in the past the US has been more successful than Europe at "crowding in" the private sector. That is, if the US administration shrinks the size of the government sector in a smart way, it could promote greater private sector investment and boost business confidence.

Outside the direct and indirect effects of fiscal policy, the US economy is already receiving a significant amount of stimulus from extraordinarily loose monetary policy. The US Federal Reserve has already committed to keep overnight interest rates near zero and to continue quantitative easing (QE3) until they have a high degree of confidence that there is a sustainable turnaround in the jobs market.

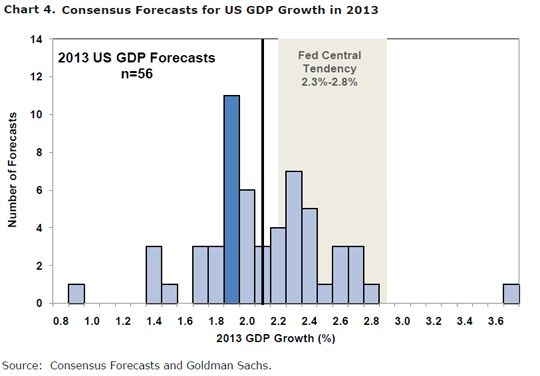

Chart 4 brings all these factors together, and illustrates the range of forecasts for US GDP growth in 2013, based on the 56 forecasters that contribute to consensus forecasts. It highlights that the majority are picking relatively slow growth in the 1.8-2.0% range, taking a view that politicians are able to "muddle through", finding an outcome that doesn't knock too much off GDP growth. Some other forecasters (including the Fed Reserve) are little more optimistic, picking slightly better growth in the 2.3 – 2.8% range. But this is still reasonably modest, and not a strong economic recovery.

Skittish financial markets

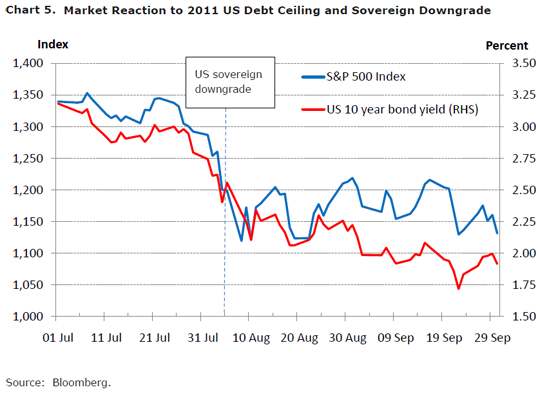

Because it has been a well-flagged risk, financial markets have been worrying about the US fiscal cliff for much of 2012, and are braced for volatility around the end of the year following the election. The memory of the US debt ceiling negotiations in mid-2011 is fresh in the mind. In that case, political grandstanding and gridlock resulted in the US losing its prized AAA sovereign debt rating. The market reaction to that event (Chart 5) provides a useful case study to think through the impact of different outcomes to the US fiscal cliff negotiations, especially the tail risks of "over the cliff" or a "grand bargain".

If politicians were to take the fiscal situation over the cliff, we believe there is scope for a market reaction that looks similar to the US sovereign downgrade in 2011. This scenario would be negative for global equities. And with the New Zealand equity market looking reasonably fully-priced, it is unlikely that our company share prices would be immune to a bout of negative sentiment.

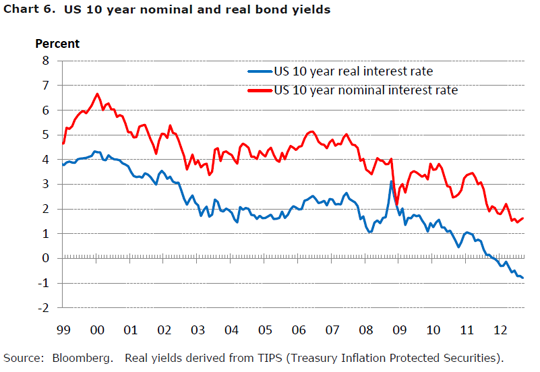

We would expect a strong flight to safety to US Treasuries, pushing down long term interest rates in the US and New Zealand. But with bond yields already at very low levels, we see less scope for these to fall as sharply as they did in 2011. Valuations in the US bond market already look stretched. One simple illustration of this is that the sharp fall for in bond yields in 2011 has already pushed real US yields into negative territory (chart 6). If politicians were able to produce a "grand bargain" this would represent a significant positive surprise for markets.

It is likely that equity markets and other risky asset classes would benefit strongly, although with the New Zealand equity market having a lower beta, there may be more opportunities for upside in selected Australian stocks. In this scenario there would be less demand for US Treasuries as a safe haven, which would see long-term interest rates rise in the US and New Zealand. But we would expect any rise in long-term bond yields to eventually be capped through ongoing purchases by the US Federal Reserve as part of the quantitative easing programme.

In New Zealand, we would expect a grand plan to have little effect on short-term interest rates, which we see as being more driven by an assessment of domestic economic momentum and domestic inflation pressures. It is also important to remember that any outcome on the US fiscal cliff will not occur in a vacuum. The very harsh market reaction in 2011 to the US debt ceiling negotiations and US sovereign downgrade was exacerbated by other events. Around the same time, data revealed that US GDP growth had surprised on the downside, and the European sovereign debt crisis was intensifying, making the markets even more skittish and nervous.

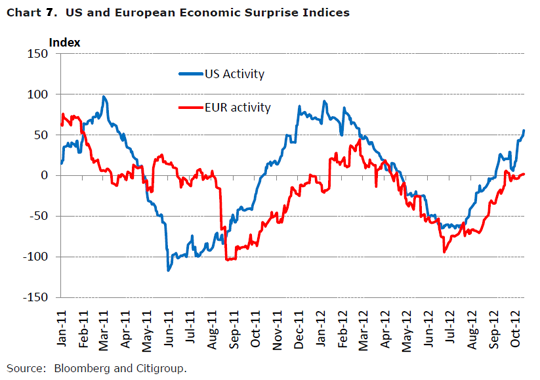

Looking forward to 2013, one of the worst backdrops would be for both economic growth to stall and for inflation pressures to emerge that removed the ability for the US Federal Reserve to keep monetary policy exceptionally loose. Over recent months the economic background in the US has been improving, with economic data tending to surprise on the upside (chart 7).

Importantly, there have been a number of indicators pointing to an improvement in the US housing market, which was the initial source of the problem that sparked the eventual global financial crisis. Subject to politicians delivering on their part of the solution to the US fiscal problem, that at least provides a supportive backdrop.

A key focus

So, in conclusion, the US fiscal cliff will be a key focus of markets after this week's elections. This is because the US fiscal stimulus measures enacted since the GFC mature in January 2013 and need renegotiation in an environment where there is likely to be a division of power between the White House, Senate, and Congress.

There is significant uncertainty about the outcome of these negotiations, with the size of the resulting fiscal headwinds ranging from 0.8 to 4.4 % of GDP. Markets are worried that there is a small chance that a breakdown in talks would take the US economy "over the cliff" - a chance we put at 5%.

We believe the "muddle through" compromise is the most likely outcome. Furthermore, unlike the failed US debt ceiling negotiations in 2011, the backdrop in recent months has been improving US economic data and a more stable environment in Europe.

As stated earlier, a "grand bargain" would be a surprise to markets and we put this chance at 10%. In the meantime, the reliance on political decision-making could keep markets nervous and volatile well into the New Year. So hold on for a bumpy ride.

*Christian Hawkesby is head of fixed interest at Harbour Asset Management.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.