If you have any doubt that we’ve wandered into a new and unexplored economic universe, consider this number: US$12.6 trillion. That’s the face value of government and corporate bonds currently trading worldwide with nominal yields below zero.

Note that word trading. These bonds are in fact trading. Liquidity has not dried up. An active market exists for negative-yield bonds. Buyers haven’t gone on strike, and sellers aren’t desperately dumping the bonds. This is weird. None of it should be happening. Plainly, however, it is happening.

Have traders and investors lost their minds? No. They are making the most rational decisions they can in an increasingly irrational world. And therein lies the problem with negative interest rate policies, or NIRP, as we now call them (not so fondly).

We don’t have infinite choices. Our decisions spring from the alternatives available to us. When all the alternatives are bad, any choice we make will be bad, too. Today we will start a two-part series on how central banks and specifically NIRP are hurting the global economy. First, a little background.

The price of liquidity

What is an interest rate? You might describe it as the price of money, or in investment terms it is the price of liquidity. You don’t have cash now, but you expect to have it in the future. If a lender believes your expectation is plausible, you can borrow the cash now in exchange for promising to replace it tomorrow. But you don’t just replace what you borrowed. You add an additional amount to compensate the lender for giving up liquidity on that money. That additional amount is what we call interest.

Now, thinking through this lending scenario, is there any way in which negative interest makes sense? Maybe. It makes sense if liquidity is undesirable. Or it makes sense, at least to some central bankers, if you want to make liquidity undesirable in order to encourage people (and lenders) to take more risk. However, the data is all beginning to show that consumers and even some businesses are actually saving more money in low-interest-rate or negative-interest-rate environments.

Why would liquidity be undesirable? It would be if there was nothing of value to buy with your money. If you’re lost in the desert, having a thousand dollars in your pocket does you no good. You would trade it all for a gallon of water. There isn’t any water, so your money is worthless. So is your credit card.

How can undesirable liquidity pertain in a whole economy? Cash is useful to the extent that you can buy goods and services, but you can only buy so much. Beyond a certain point, liquidity becomes bothersome because you have to store and protect it. This effort consumes time – the one resource we can’t replace.

Is it coincidence that cash is losing value at the very time technology has brought the whole world to our fingertips? What would the knowledge you can now get for free on the internet have cost in the 1970s? Quite a lot, I assure you.

I say all this to make a point: Even if we didn’t have central banks manipulating interest rates, rates might be very low just by virtue of our modern technology and circumstances. I actually think they would, but that is not an experiment we will be able to run. I’m just speculating about what might happen – which, come to think of it, is what central banks now do. They speculate that their radically new actions will have particular results, but they have no empirical evidence to verify that this is true. So when you add central banks to the equation, interest rates get even lower because they manipulate them down. But that’s quite a different scenario than the below-zero yields we see in Europe and Japan right now – and may well see in the US when the next recession strikes.

NIRP Problem #1: Failure to Stimulate

The Federal Reserve’s mission is to maintain a stable inflation rate while spurring employment. Its main tools are control over the money supply and interest rates. Lately exercising that control has meant keeping interest rates extremely low, especially by historical standards.

That’s simple enough, but recognize the grand and unproven assumption here: Lower interest rates will create higher demand for goods and services. If that’s true, the Fed can stimulate economic activity by pushing rates lower and keeping them there.

But is it really true? Certainly not for the last eight years. We’ve had short-term rates near zero the entire time and long-term rates at historical lows. Yet, as measured by GDP or any other standard, economic growth has been mild at best. This dearth of desired results is a real problem for central bankers everywhere.

It gets worse. Not only have very low or negative interest rates failed to stimulate demand, they have arguably reduced demand as people save more and spend less.

Why do people do this? Imagine you’re a retiree trying to live off the interest on your savings. In order to get any income at all, you’ve had to take on more risk by holding long-maturity bonds, junk bonds, preferred stocks, etc. You compensate for this risk by giving yourself a bigger savings cushion. That means you have to reduce spending somewhere else.

Do central bankers not see this? They can surely read the same studies I do. In any case, the financial industry is waking up to the fact that something is very wrong.

Last week the Financial Times had an excellent column by Eric Lonergan, a macro fund manager at M&G Investments and proprietor of PhilosophyofMoney.net. He quickly and eloquently dismantled the foundation of modern central banking.

The idea that lower interest rates raise demand is based on the view that households attempt to smooth their consumption over time. This assumed relationship has little empirical support, and there are good reasons, particularly when rates are extremely low or negative, to doubt it. High existing debt levels, or poor creditworthiness, are more realistic constraints on spending than higher interest rates.

And what of savers? Lower rates have a depressing effect on household incomes, through reduced interest on savings and pensions. It is likely that in relatively wealthy economies – with rising healthcare costs, increasing longevity and uncertainty over pension funding – households respond to lower income on their savings by trying to save more. If this outweighs the reduced incentive to save, the actions of central banks are self-defeating. The relationship of spending to lower interest rates may well be the reverse of that assumed by policymakers. If consumers do not respond to lower rates by spending more, this places an additional onus on the corporate sector.

Yet corporate investment appears similarly unresponsive. Investment decisions have financial consequences over many years, and are more influenced by beliefs about future growth and attitudes to risk than by overnight interest rates set by central banks.

Indeed, cash hoarding is exactly what we see corporations doing, or at least those corporations that can make a profit in this environment. Apple, Microsoft, and all the other US tech giants have billions stashed outside the country for tax reasons. But they would still keep much of that money in cash even if the tax disadvantage went away. They have no need to spend it, very little to invest in, and see no reason to risk losing it or to bring it back into the United States to pay high corporate taxes. So there it sits, not stimulating anything.

As for consumers, I think Lonergan explained it well: “High existing debt levels, or poor creditworthiness, are more realistic constraints on spending than higher interest rates.” Most Americans have excessive debt, low credit ratings, or both. Low or even negative interest rates will not make them spend more money as long as that is the case.

NIRP Problem #2: Betraying Lord Keynes

In 2008 the whole financial system was on the verge of collapse. Then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke saw little choice but to use every tool in the Fed’s toolbox. So he cut rates, among other things. As Walter Bagehot noted (there’s more on him below), the purpose of a central bank is to provide liquidity at a price in the middle of a crisis. The Fed decided to set the price very low, but they did do the appropriate thing by adding liquidity. However, they overstayed their welcome because of lingering timidity.

I think they made the right move in 2008, even if I disagreed with the actual way they implemented it, but keeping rates near zero years later is harder to defend. Doing so has punished savers without stimulating growth. Why the Fed’s hundreds of PhDs didn’t know this would happen is beyond me. Even their demigod, John Maynard Keynes himself, said interest rates have to reflect reality.

Even if I disagree with some of Keynes’s conclusions, and especially with the way his disciples have used his work, I have to recognize and acknowledge his brilliance. In his magisterial General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, chapter 21, Keynes describes his “theory of prices.” This includes interest rates, which as we saw above is simply the price of liquidity. You can read the full chapter here. I will quote from its last section (this gets a little academic, but work through it, especially the areas that I put in bold). Remember, this was in the ’30s, in the middle of the Great Depression.

Today and presumably for the future the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital is, for a variety of reasons, much lower than it was in the nineteenth century. The acuteness and the peculiarity of our contemporary problem arises, therefore, out of the possibility that the average rate of interest which will allow a reasonable average level of employment is one so unacceptable to wealth-owners that it cannot be readily established merely by manipulating the quantity of money. So long as a tolerable level of employment could be attained on the average of one or two or three decades merely by assuring an adequate supply of money in terms of wage-units, even the nineteenth century could find a way. If this was our only problem now – if a sufficient degree of devaluation is all we need – we, today, would certainly find a way.

But the most stable, and the least easily shifted, element in our contemporary economy has been hitherto, and may prove to be in future, the minimum rate of interest acceptable to the generality of wealth-owners. [Footnote 2: Cf. the nineteenth-century saying, quoted by Bagehot, that “John Bull can stand many things, but he cannot stand 2 per cent.”] If a tolerable level of employment requires a rate of interest much below the average rates which ruled in the nineteenth century, it is most doubtful whether it can be achieved merely by manipulating the quantity of money. From the percentage gain, which the schedule of marginal efficiency of capital allows the borrower to expect to earn, there has to be deducted (1) the cost of bringing borrowers and lenders together, (2) income and surtaxes and (3) the allowance which the lender requires to cover his risk and uncertainty, before we arrive at the net yield available to tempt the wealth-owner to sacrifice his liquidity. If, in conditions of tolerable average employment, this net yield turns out to be infinitesimal, time-honoured methods may prove unavailing.

To paraphrase, Keynes is saying here that a lower interest rate won’t help employment (i.e. stimulate demand for labor) if the interest rate is set too low. Interest rates must account for the various costs he outlines. The lender must make enough to offset taxes and “cover his risk and uncertainty.” Zero won’t do it, and negative certainly won’t.

The footnote in the second paragraph is important, too. Keynes refers to “the nineteenth-century saying, quoted by Bagehot, that ‘John Bull can stand many things, but he cannot stand 2 per cent.’”

Is Keynes saying 2% is some kind of interest rate floor? Not necessarily, but he says there is a floor, and it’s obviously somewhere above zero. Cutting rates gets less effective as you get closer to zero. At some point it becomes counterproductive.

The Bagehot that Keynes mentions is Walter Bagehot, 19th-century British economist and journalist. His father-in-law, James Wilson, founded The Economist magazine that still exists today. Bagehot was its editor from 1860–1877. (Incidentally, if you want to sound very British and sophisticated, mention Bagehot and pronounce it as they do, “badge-it.” I don’t know where they get that from the spelling of his name. That’s an even more unlikely pronunciation than the one they apply to Worcestershire.)

Bagehot wrote an influential 1873 book called Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market. In it he describes the “lender of last resort” function the Bank of England provided, a model embraced by the Fed and other central banks. He said that when necessary, the BoE should lend freely, at a high rate of interest, with good collateral.

Sound familiar? It was to Keynes, clearly, since he cited it in the General Theory. Yet today’s central bankers follow only the “lend freely” part of this advice. Bagehot said last-resort loans should impose a “heavy fine on unreasonable timidity” and deter borrowing by institutions that did not really need to borrow. Propping up the shareholders of banks by lending low-interest money essentially paid for by the public when management has made bad decisions is not what Bagehot meant when he said that the Bank of England should lend freely.

How did the Fed act in 2008? In exact opposition to Bagehot’s rule. They sprayed money in all directions, charged practically nothing for it, and accepted almost anything as collateral. Not surprisingly, the banks took to this largesse like bees to honey. Taking it away from them has proved very difficult. We now find ourselves in an era of speculation about what will happen when interest rates are raised.

(By the way, thanks to reader Richard Field for pointing me to the above Keynes quote. It’s amazing how much help you can get from complete strangers on Twitter. I will admit that I ignored Twitter for a long time, but now I find myself roaming it when I’m sitting around with nothing else to do and my iPad in hand. You should consider following me on Twitter, right here.

NIRP Problem #3: Policy Paralysis

What would Keynes and Bagehot say about today’s interest rates, or lack thereof? Their beloved Bank of England last week cut its benchmark rate to a record-low 0.25%. That is not what anyone would call a “heavy fine on unreasonable timidity.”

The problem is how to correct this policy error without causing yet more turmoil in the markets. On that, I’m stumped, and so are the central bankers. If they could wave a magic wand and get short-term rates back to, say, the 3% region where they were at the end of 2007, I’m sure they would be delighted. And we might see some positive effects. Savers would receive more income, for sure. However, this magic trick would also crater the stock market. The one thing we know is that the Federal Reserve is now in the thrall of the stock market.

The S&P 500 dividend yield is currently around 2%. To earn it, you have to accept the principal risk and volatility inherent in stocks. No one would do this if they could earn the same or even more in Treasury bills or bank savings accounts. An unexpected rate normalization by the Fed would jar the stock market downward to restore balance to the equation of risk and reward.

So we are stuck. The Fed can’t use the only available exit without slamming the markets. The only alternative is to stay in the trap and walk around in circles, hoping something will change. Someday it will, but I expect that it won’t be a pleasant change – but rather one that, in the minds of the central bankers, requires an even more unusual monetary policy. We will examine that potential in depth and detail next week. Until then, the room will get increasingly uncomfortable.

NIRP Problem #4: Killing Insurance Companies and Pension Funds Softly

Insurance funds make a profit by taking your money and turning it into long-term loans. They use the money they make, along with your premiums, to cover your insurance risk in the event of need. Pension funds generate profits from long-term loans to grow the money they need, along with your contributions, in order to pay for your retirement. They have built into their models a reasonable long-term return – at least from a historical perspective – on bonds and the stock market.

This model can turn fall apart very quickly under a very-low-interest-rate or NIRP regime. The returns insurers and pension plans make on their investments no longer adequately fund the promises they have made. It gets even worse with NIRP. Think of the poor insurance companies, monstrously bigger than banks in Europe, that are forced by regulations to invest in long-term government bonds, many of which are now earning negative returns. How in the Wide, Wide World of Sports can you make a positive return when you are forced to invest in negative interest-rate bonds?

Then we come to the banks. What happens when they make negative returns on their cash? We haven’t seen extreme scenarios yet, as far as I can tell, but the banks are definitely getting squeezed. Last week Royal Bank of Scotland warned some corporate customers that it may start charging interest to hold their deposits. Some German banks have already done so.

Knowing this practice is a problem, banks try to offset NIRP by cutting other costs: by automating more tasks, laying off employees, closing branches, etc. This year we’ve heard a lot about banks investing in blockchain ledger technology – the same engine that drives Bitcoin digital currency. The banks aren’t doing this because they love Bitcoin. Their interest is in reducing costs, and blockchain applications promise to help them do it. That technology will lead to more job losses down the road.

Between NIRP and assorted technology and regulatory changes, the banking industry is on its way to becoming a kind of regulated utility. This shift might mean fewer bailouts in the future, but it will certainly mean less risk-taking and speculative lending and investing by banks. To the extent this dynamic makes it harder for worthy businesses to get capital, it will contribute to the generally low-growth economic conditions we’ve seen since the crisis.

I have written several letters about the plight of pension funds worldwide. I am gathering information on the situation with insurance companies, which my initial research shows is even more dire. If you have something I should know, please send it to me.

NIRP Problem #5: Distorting Signals

ECB President Mario Draghi famously pledged to do “whatever it takes” to restore eurozone growth. His attempts to fulfill that promise have led to NIRP and other bizarre policies like the central bank’s massive asset purchases.

Whether the ECB’s various interventions are helping the eurozone economy is not yet clear, but they are certainly having consequences, among them the appearance, if not the reality, of central bank interference and favoritism.

The ECB’s corporate bond-buying program, for instance, was originally going to purchase already existing bonds on the open market. However, it has evolved into a kind of closed market in which a favored group of companies issue bonds customized to the ECB’s specifications.

Last week the Wall Street Journal reported that the ECB had gone a step further, buying bonds directly from two Spanish companies through private placements. In other words, the ECB bypassed public markets completely and simply loaned money to selected companies. They weren’t even going to tell anyone. Someone at the WSJ, God bless their attention to detail, did some data mining and found the two private placements. One was to the Spanish oil company Repsol and the other to Iberdrola, an electric power utility. Morgan Stanley acted as underwriter in both cases. I wish my friends at Morgan Stanley would arrange to give me long-term money that cheaply. Just saying.

Now maybe the ECB had good reason to make these two transactions privately. I don’t know, and they won’t say. But we shouldn’t have to wonder. The reality is that the ECB is buying so much of the corporate bond market in Europe that it is becoming difficult for the bank to find things to purchase on the public markets, and so they are beginning to look into the private markets. One of the great ironies is that European divisions of US companies are creating loans so they can get the ECB to buy them. It makes perfect sense from the company’s standpoint, of course – let’s hear it for replacing expensive loans with cheap ones. That’s an easy way to make an executive look smart.

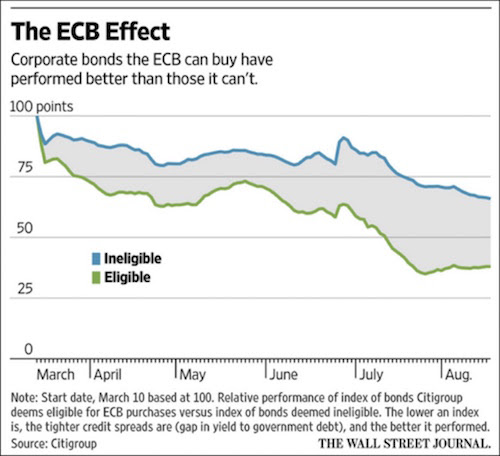

The problem is that this sort of thing generates false market data that leads other players to make bad decisions. Consider this chart from the WSJ. It depicts credit spreads of European corporate bonds. Lower numbers mean a tighter spread, which is good from the issuing company’s point of view because it means their cost of capital is lower.

We can see here that bonds eligible for ECB purchase (the green line) have consistently outperformed other bonds since the program launched. The advantage seems to be growing with time, too. Are these bonds really better, or are they just getting the benefit of ECB’s buying – buying that could end at any time? Technically, we don’t know. There is no way to tell. My guess? We will know when the ECB runs out of bonds to buy and starts having to loosen its determination as to what it can buy, such that more corporate bonds become eligible. If this new category of bonds sees its credit spread drop, too, we will know for sure that the critical variable at work is not bond quality, per se, but the ECB’s purchases.

European bond investors don’t have clean data that will let them make confident decisions. Some will no doubt withdraw from the bond market, leaving the ECB even more of a monopoly purchaser than it already is. That’s the opposite of what ECB claims to want, but its strategy is making the problem worse, not better.

NIRP Problem #6: Repressing Retirees

I saved this one for last because it is, for me, the most enraging consequence of ZIRP, NIRP, QE, and all the rest. Savers, the people who read my newsletters and buy my books, are paying the price of our central bankers’ mistakes and arrogance. People who did nothing to cause this situation are getting punished for it.

Back in February I wrote about how ZIRP and NIRP are “Killing Retirement As We Know It.” I don’t often quote myself, but this is important. Follow the link if you want to read the full section. I was talking about how retirees could once live off their savings without too much trouble.

It was even simpler if you had an employer or union pension plan to do the work for you. Pension plans pooled people’s money, calculated how much cash they would need to pay benefits in future years, and built portfolios (mainly bonds) to match the liability projections. Government and corporate bonds yielded enough to make the process feasible.

Younger readers may think I just described a fantasy world. I assure you, it was very much a reality not so long ago. Ask your grandparents if you don’t believe me. However, you may find them in a state of shock today because they thought the fantasy would last forever. Indeed, their financial planner probably told them they could count on drawing down 5% of their portfolio per year to live on, because the income from the investments in their portfolio would more than make up for the drawdown.

None of this is possible today. Neither you nor a massive pension plan acting on your behalf can generate enough risk-free income to assure you a comfortable retirement.

Why not? Because our monetary overlords decreed that it should be so. Retirees and their pensions are being sacrificed for what now passes as “the greater good.” Because these very compassionate overlords understand that the most important prerequisite for successful future retirements is economic growth. And they think that an easy monetary environment is the necessary fertilizer for that growth. So, when they dropped rates to zero some years ago, they believed they would soon be able to raise them again – and get people’s retirements back on track – without risking future economic growth. The engine of growth would fire back up, and everything would return to normal.

So much for the brilliant plan. You and I, the expendable foot soldiers in the war to reignite growth, now gaze about, shell-shocked, as the economic battlefield morphs from the Plains of ZIRP to the Valley of NIRP.

Note: Next week we are going to examine the “causality” of low interest rates and easy monetary policy and their connection with the mediocre recovery we have experienced. I am going to argue that the US economy has recovered (to the modest extent that it has) in spite of monetary policy, not because of it, just as economies have in every recovery since the Medes were trading with the Persians. Current Fed policy is actually distorting the process, not helping it.

The Federal Reserve’s choice to keep interest rates near zero for years on end has exacted a direct and sometimes devastating human cost. Real people who worked hard all their lives and made sensible decisions about retirement are, to be blunt, getting the shaft.

----------------------

* This is an abridged article from Thoughts from the Frontline, John Mauldin's free weekly investment and economic newsletter. It first appeared here and is used by interest.co.nz with permission.

37 Comments

Reading this there is a factor that is not mentioned. Using NIRP to stimulate growth has an assumption that is not mentioned here, and that is that the majority of the population has the spare funds to spend. The problem is that they don't. Prices have been going up forever just about and money pumped into the economy tends to only get to the wealthy who, we have seen, hoard it rather than spend it. And prices still haven't come down. Statistics tell us that under the current economics the middle class is being gutted, forced down not up, which means they have even less money to play with, and the GFC has made many of them wary about debt. These are issues with the free market economies, rampant greed has seen middle and lower class incomes, and therefore lifestyles eroded over decades as the wealthy business owners have tightened the screws on their work forces, reducing pay, removing conditions, demanding more for the same or less all in the name of growing profits (the great economic myth) while the workers who actually create that wealth lose more and more.

Want to stimulate growth? regulate to make jobs 40 hours per week at a pay rate that delivers a reasonable lifestyle. Regulate to stop people manipulating economies and markets. Make housing, food and good affordable for all. And remove all loopholes that allow corporations and business's avoid paying tax.

In my mind it has distorted economics by allowing over supply of goods, by propping up companies that should have folded, creating deflation in wages and goods and the never ending circle of trying to artificially create growth to match the supply

Whilst those that had capital instead of spending instead took the opportunity of cheap assets and credit to buy, forcing those up beyond fair value.

it should have been short and sharp but now its too late, like a drug we are addicted to it and the only way to get off will be cold turkey

GFC version 2

This article has nailed it . Its a fact that those of us with surpluses have taken less risk and ended up saving more, simply because , in my case , instinctively I can see we are in a dangerous place , where central banks have gone mad .

I for example started paying down all debt in 2008 and by 2010 had paid off the mortgage and all my debt bearing assets , in both my personal life and my business .

Now we have zero debt , and a cash pile that I don't know what to do with , and I refuse to buy any more over-priced equities , I refuse to buy a second over-priced Auckland residential property , and I am not prepared to take any new business risk .

Things will change , so for now I will sit on my hands and do nothing

How correct. Infaltion was low when ocr was 2.5%, is low when 2% and will be low even at 1.5% or even at 1% so how does it help.Same applies to NZD compare to USD as more than ocr it depends on what happens in usa.

Well, if you target inflation, but leave a whole bunch of stuff out of the inflation calculations, it seems only natural that's what the outlet will become.

Do we really have to explain why certain things are omitted, again?

Nothing should be omitted.

I have a fixed income - it is not unlimited.

If rent, mortgage, or interest payments increase. Then I have less money to spend.

If I spend less (along with everyone else) then we see deflation. Ignoring obvious forms of spending is a stupid economic theory that is being proven wrong as we speak.

I saw a comment on MSM the other day how a rentier was complaining how her rent had gone up by 50 per week for the last three years and her wages had not gone up at all, now she was in a situation of soon not being able to afford to rent at all.

the interest I took out of it was your point that is 50 per week she is now not spending in the shops, is the landlord spending it in the shops, I doubt it most likely paying down debt or another loan for another house

so headed offshore to one of the big banks.

and they wonder why they can only boost consumer spending by bringing in money with more immigration and can not get CPI inflation to rise

Just a wee help out ST, "rentier" refers to the group that are the landlords, who has ownership, the person you speak of is a renter (no "i") - thus we have "the rise of the rentier class".

Sadly it is an all to common problem these days. One that is seemingly overlooked by Government and business.

Rent is most definitely included in the CPI measure, already.

Your mortgage/interest/financing rates are intrinsically related to the inflation measure, so we can't include those.

Asset classes, well, firstly, we just don't consume these. These are long(er) term investment tools. Including them would just mean that consumers/demand side had an incentive to manipulate the core inflation measure and everything indexed to it. Forward investment expectations would be intrinsically linked to a horde more factors.

If you think the core measure is messed up without asset classes, you would hate to see it inclusive of asset classes.

Your comment "...manipulate the core inflation measure and everything indexed to it." is the root cause of the problem.

Business have been doing this for ages. Large B2B contracts are constructed with a CPI multiplier to save renegotiation.

Inflation was stable because of this link (if you all agree to only raise 3% year on year, then inflation will only ever be 3%). It worked well for ages, actual production costs like wages were controlled by the company and were kept stagnant. Effectively ensuring that the company would make an additional 3% profit year on year. Everyone was happy (except for the poor old workers - who saw costs go up, but wages stagnate)...Then the oil price plummeted and changed everything.

Companies started looking at the CPI in the contract and going "hey your transport/generation/whatever costs have dropped significantly, you can't just whack CPI on, that's just profiteering"

Next thing you know, sharemarket starts dropping (as the free profit has dried up) and then the CPI starts to decrease.

Reserve banks around the world slash interest rates, print money, and what ever else they can think of. Yet they miss one key point - no where is interest rates/money in circulation measured in the inflation calcs.

i.e. Interest rates will never impact the CPI, unless they themselves are factored in (i.e. mortgages).

CPI is unlikely to go negative as the companies have all now redone their contracts factoring in the lower oil costs. They can now all jump back on the "linked to CPI contract" bandwagon, then just sit and wait for the oil price to go up again.

When that happens, CPI will go up again (after all oil (petrol) is factored in to costs and generally goes up at a far higher rate that it goes down) When that happens all the little reserve bank governors around the world will say "see - we told you we would fix it"

"Business have been doing this for ages. Large B2B contracts are constructed with a CPI multiplier to save renegotiation."

Which of these businesses are in the business of holding long term assets for capital gain?

Also...

"Reserve banks around the world slash interest rates, print money, and what ever else they can think of. Yet they miss one key point - no where is interest rates/money in circulation measured in the inflation calcs.

i.e. Interest rates will never impact the CPI, unless they themselves are factored in (i.e. mortgages)."

...I just want you to re-read that statement. Please let us know when you find the mistake.

my point is the flow of money out of consumer spending into the purchase of assets and flowing offshore.

and the effects that is having on CPI inflation, if you keep taking money out of the system you will not get it.

it all goes back to if we let one part get away it can distort the real economy.

i am not saying include asset prices but they need to be kept in check otherwise they feed onto distortion

How to control them is the question, this government says only supply.

the RB says LVR

me I say demand , supply, change tax laws, income to loan , stop selling outside NZ. we need a wide range of measures to get it back to a level that it stops hurting the consumer economy

A very sensible answer, at that.

And, one which I wasn't arguing about.

I'm not saying the measure is perfect, I just try to explain why we cannot have long term asset classes in a core /consumption index.

We use CPI as the rate of inflation, a measurement of the rate of fall in the purchasing value of money. It’s got nothing to do about what is consumed or not. Today’s dollar is worth a lot less than 15 years ago, because it buys a lot less of that most important requirement for financial security, family and retirement… a home. A lot less than what the CPI measurement says.

Other asset classes are inflated as well, just look at the P/E ratios of the stock markets. S&P500 is 25; the long term median is 14.

CPI also has fixed weightings for things like rent which are out of whack with reality. There is also something called substitution, if the price of an item goes up too much it can be substituted with a cheaper item, talk about a fiddle.

I don’t think we could get any more messed up than now. Hyperinflation in the housing and debt. Careers loosing most of their value, GFC, QE and the lowest interest rates since the Black Death. So I think you do have to explain why certain things have to be omitted, I haven’t seen a good argument. Inflation has been under-reported.

"We use CPI as the rate of inflation, a measurement of the rate of fall in the purchasing value of money. It’s got nothing to about what is consumed or not."

...Do you people ever read what you write?

"I don’t think we could get any more messed up than now. Hyperinflation in the housing and debt. Careers loosing most of their value, GFC, QE and the lowest interest rates since the Black Death. So I think you do have to explain why certain things have to be omitted, I haven’t seen a good argument. Inflation has been under-reported."

It has been explained time and time again. It is not my fault if you can't understand why interest rates shouldn't be linked to appreciating assets over consumed goods.

nymad... Do u ever ponder the efficacy of mainly using the CPI, in regards to Monetary policy.?? ( serious question...I'm not having a go at u ).

In a global world... An increase in aggregate demand often results in an increase in the quantity of goods sold rather than an upwards pressure on prices... (ie. the transmission mechanism between credit growth and prices is not what it used to be )

here is a link to a chart which breaks CPI into component prices... I found it interesting..

http://pc.blogspot.co.nz/2016/08/prices-are-stable.html

As things stand... the current policy target framework ignores very important issues such as aggregate debt levels rising faster than aggregate incomes.....and the long term consequences of that.

The GFC brought to light a few very important issues in regards to sustainable levels of credit growth .

( one would think this might fall within a Central Banks mandate of long term price stability, in regards to money supply/credit )

Yes I do read what I write, no I have not seen a good explanation defending CPI, and you haven't come up with one either, you just insult the intelligence of people who question it. But look at the results... CPI targeting is broken. Appreciating assets? No it's inflating assets.

NIRP is just a failed economic system on standby. An economic model used by those who cant admit a Fiat Currency has exceeded its actual lifespan

What's the alternative?

You lift interest rates and strategically link the OCR to house price inflation is how. Then all that funny money being pumped into the system in the form of new created debt IS accounted for, for its adverse effects on the buying power of that fiat currency. really f...ing simple. But yeah, i know you fail to grasp it

So you mean include land value in the CPI/core inflation measure, then?

Haven't we talked about this? Scroll up.

Also, that isn't a solution for the fiat currency thing that you were bemoaning...Unless you are now implying that you are backing a government issued currency with private assets?

One thought. If we stopped or slashed immigration then competition for staff would drive up wages and salaries. i.e. inflation. It would also help with that little housing problem that we have.

That would be far too sensible!

Our two biggest problems - unaffordable housing and a median income folk can't afford to live on - with one simple solution.

The problem is that it would require the government to step up and take some responsibility because this tool, along with so many others that could address our many problems, is not available to the Reserve Bank, only the Government. The Government seems to take a totally hands off approach spinning platitudes and B.S. from the sidelines. May be they think it is safer doing that because if you do nothing you can't be held accountable for any mistakes that you may make. That may work for a while, but as we are starting to see it will catch up with them eventually.

A further observation would be that if the government followed my suggestion that vast bulk of the population would benefit from higher wages at the expense of the very wealthy few. My suggestion is so obvious that it is hard to believe that government is not aware of it. Clearly their reasons for not doing this is that their loyalties lie totally with the wealthy few and the not the vast majority, who voted them into power.

Nope. Those companies that can would just offshore work. Those that can't would probably go out of business competing with overseas companies. You would however get inflation + recession topped off by a sweet smooth depression.

Excellent article as we have come to expect from John Mauldin. Just shows what a God awful mess we've got with the CBs backed into a corner and the economic world turned upside down. I don't think they've really got a clue or are things now so fundamentally FUBARed that there is no realistic way out?

Thanks for the good article John. I have thought that something is fundamentally wrong with this approach and where we are headed for some time now. Your article puts some good perspective and background to this.

I suspect that part of the problem is that it is being considered largely only in the Central Bank paradigm.

My cynical side questions whether the combined intellect of all the worlds governments and reserve banks is really this poor and I am tempted to suggest that it suits some people because they are making a lot of money from this approach. As per the old adage ' follow the money." Who is benefiting ?

"My cynical side questions whether the combined intellect of all the worlds governments and reserve banks is really this poor......"

Go with that gut feeling cause its the truth. The whole thing is just a dirty wee game of 'keeping the status quo'.

I love his "Why the Fed’s hundreds of PhDs didn’t know this would happen is beyond me" line.

It might be because you have no qualifications in Economics or Finance, John.

Other than that, good analysis.

I don't think any economist has adequately described the full nature of interest. They call it the cost of money, but really it is the cost of future resources. For it is resources, not capital or labour, that supply the yield that capital demands.

A Great Article.

This interest rate madness started with "The Maestro" Alan Greenspan Fed chair back in the late 80's a path continued on by Bernanke, Yellen and adopted by other misguided central bankers. Along this journey they have resorted to more and more extreme monetary measures in the belief these policies will fulfil their economic goals including trying to avoid the realities of capitalism i.e that recessions occur from time to time and are often painful. The result; colossal malinvestment, the mispricing of markets and the mispricing of virtually all assets, the massive accumulation of debt by Government’s, Corporates and individuals and the continued survival of entities which would normally have failed is now on scale beyond any comprehension. It hasn’t worked as they believed it would i.e creating a sustained economic recovery to wash away the ills of the past. They crossed a line many years ago and are now trapped in a desperate place unable to go back to normality without causing huge economic upheaval. What will they do probably keep doubling down until they totally destroy any confidence left in paper money the result being………

Good article Mr Mauldin. I agree with you and Colin above that the central banks and goverments will keep going round and round until the collapse of paper money. The rise of the blockchain currency will ensue... hard assets are required for the transition period.

I still reckon we are in a deflationary cycle , the costs of food is now also falling in NZ , all food except the retail price of milk

How refreshing to read an intelligent, well written article

It's great , we've had 2 this last week ! Keep them coming !

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.