This week's Top 10 comes from Jeremey Couchman, a senior economist at Kiwibank.

As always, we welcome your additions in the comments below or via email to david.chaston@interest.co.nz.

We are keen to find some new Top 10 contributors so if you're interested in contributing, contact gareth.vaughan@interest.co.nz.

1) If cash is king, the US dollar is the king of kings.

Emerging market fortunes are inextricably linked to the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) policy cycle and importantly the US dollar. This is a key reason behind the current wobbles experienced in emerging markets (EM). Hitting the headlines of late has been the troubles facing Turkey and Argentina. But financial market concern has stretched to other EMs such as South Africa, Brazil and Indonesia.

When the US dollar depreciates, EMs tend to perform well. And when the dollar goes up, not so well. Since late 2015 the Fed has embarked on a period of policy tightening, hiking interest rates (the Fed’s funds rate is now higher than NZ’s OCR) and allowing their massive asset holdings to gradually roll off (from quantitative easing, QE, to quantitative tightening, QT).

Rising US interest rates have enticed capital to flow back into the US, helping to propel the US dollar. Along with some Trumpian tax incentives. If you are an investor with exposure to EMs, why take the added risk when returns are on the rise in the US? The dollar index has lifted around 6.5% since the start of the year, and 20% since the end of the Fed’s QE. Meanwhile, several EM currencies have nosedived against the dollar. The Argentinian peso has more than halved in value over the last year alone. A strong dollar hurts EMs.

2) We only accept dollars here buddy!

A feature of many EMs is that their government debt is often denominated in foreign currency. This is fine when your currency is strong, and your economy is buoyant. The problem is when things are not fine, and you’re hurt at precisely the wrong moment. Investors are more than happy to lend (and capture higher returns of course), while principal and interest payments are affordable.

But when the party stops, and your currency is no longer the flavour of the month, it’s harder to entice foreign lenders. As EM currencies fall, the size of their foreign debt obligations snowball in local currency terms, and interest payments to service that debt quickly become debilitating. We are much more fortunate here in NZ, and deservedly so. Investors look at us and see a stellar track record in repaying our debts, a stable government, and solid (and fiercely independent) institutions. We can pay our way in the world and nothing suggests this is about to materially change. Investors are happy to take the risk on the NZ dollar, so our debts are paid in New Zealand dollars.

That means our currency can fall, and our debt repayments stay the same. It’s the foreign investors who wear the potential loss in their currency terms. This is a positive feature of NZ, and most developed economies. Our floating currencies actually can help us ride out the economic storms, as they decline. We have earned this right.

3) Commodities are priced in, you guessed it, the US dollar.

The production and exporting of commodities are cornerstones of many EMs. Think beef from Argentina, crude oil from Venezuela, iron ore from Brazil, and palm oil from Indonesia. On the world market, many of these commodities are priced in US dollars, not, for instance, the South African rand. When the US dollar is high, the price of the commodities tends to drop. This causes the double whammy for EMs of rising debt payments and falling export receipts that help to pay down these debts.

4) The temptation for some can be too much.

In the past, some EMs have got themselves into all sorts of mess by intervening in currency markets, despite claims that their currency floats - the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s is one such example (see below). It can be tempting for some in power to intervene in currency markets as it delivers strong economic outcomes - well in the short-term. But this can’t last. Many central banks around the world intervene in currency markets. Some, like our own RBNZ, are allowed to intervene to take the edge off extreme currency values. But in a market as large as global currency, this approach can’t be sustained indefinitely – well not if you want independent monetary policy and free capital flow at the same time (this is known as the economic trilemma).

5) The 90s Asian Financial Crisis: A shock close to home.

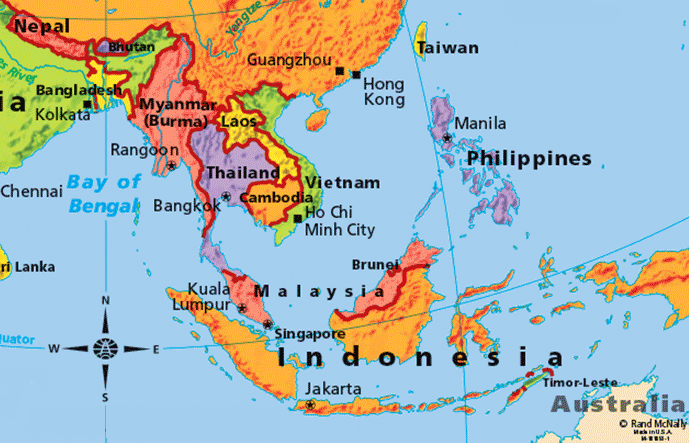

Back in 1997, our very own Bic Runga was gaining traction with her first critically acclaimed album Drive, and financial markets in Asia were going into meltdown. This came to be known as the Asian Financial Crisis. Starting in Thailand the crisis spread through much of East Asia and was also felt in countries exposed to the region -such as NZ. Under mounting pressure, and dwindling foreign currency reserves, Thailand kicked things off by massively devaluing the baht against the US dollar. Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia soon followed.

These currency devaluations exposed large foreign debts across Asia that had built up in the preceding years. Investors got flighty, contagion ensued, and economies around the region experienced a deep recession. Our strong trading ties with this part of the emerging world hurt us and our currency also. But we came out relatively unscathed. It helped us get rid of the RBNZ’s MCI regime too.

6) The Global Financial Crisis was truly a global event.

While the GFC of 2008/09 emanated from the US and Europe, EMs were not immune from its fallout. Commodity prices, and the currencies built on them were shaken. China in particular got a reality check from the GFC. Leading up to the GFC, the Chinese economy had great success in its investment and export focused model of growth. This led to huge trade surpluses with the developed world, hungry for Chinese manufactured goods.

However, China’s biggest customers were the same countries that were at the centre of the GFC. Export demand for Chinese manufactured goods dropped, and this led to a change in strategy from Chinese authorities. China has a well-documented emergent middle-class, and economic policy switched to more consumption and import driven growth.

This is not to say exports are no longer a major part of the Chinese economy. The lesson here is that having a single strategy for growth is a risky one. In this instance, the global economy was fortunate that China was able to buy its way out of this trouble by implementing significant monetary and fiscal policy stimulus.

7) A party that ended with a tequila slammer, and a hangover.

Just two years before the Asian crisis, we had fun in the sun. Let’s not forget the Tequila crisis of 1994. No, there wasn't a shortage of tequila at spring break, or Otago University. There was a Mexican crisis. Speculators came, they saw, and soon found themselves conquered. It was only after the US and IMF bailed out Mexico that the crisis ended.

8) From a tequila slammer to a Moscow mule (or is that donkey?)

Russia's twin default and devaluation in 1998 was another interesting period (linked to the Asian Financial Crisis). Fuelled by the mighty hedge funds, like LTCM, the Russian crisis quickly went global as hedge funds were forced to cover calls on worthless Russia bonds. As is always the case, investors fled for the safety of US bonds and dollars, and the Russian Rouble tumbled.

9) The rise of the hardman.

In EMs such as Venezuela, Turkey and even Russia, where checks against power are flimsy, economic crises seem to have spawned the rise of the autocrat. Unchecked leaders can make devastating decisions such as the case of Venezuela.

Following a deepening economic crisis in Venezuela in the late 1990s, a very charismatic leader by the name of Hugo Chavez emerged. Chavez proved very popular in the South American country with his massive social welfare programmes, free education and heavily subsidised petrol prices. Venezuela was the envy of Latin America in the early 2000s, but much of this was a just a facade. Venezuela’s prosperity was almost entirely funded by its massive oil wealth.

Fast forward to 2014 and oil prices fell out of bed. Venezuela’s economy and Chavezism (Hugo Chavez’s brand of socialism) came unstuck. This has had disastrous consequences for many ordinary Venezuelans. Adding to this was the new, but deeply unpopular President, Nicolás Maduro. Maduro has crushed political rivals, denied Venezuelans their democratic voice, and has ploughed on with unworkable economic policies. Hyperinflation is now entrenched, unemployment is through the roof and a humanitarian crisis is developing on Venezuela’s boarders as millions of people flee.

Venezuela 2-year bond yield overview

10) Argentina and Turkey: the latest chapter in the litany of EM crises, but certainly not the last.

Argentina is in a tough spot, recently putting its hands out to the IMF for a record bailout to ease the burden of its crippling foreign debts. The economy is contracting, and the peso has plunged against the dollar. The current crisis could not come at a worse time for the country. Not that long-ago Argentina reengaged with global debt markets, after President Mauricio Macri smoothed the waters with foreign creditors burnt by Argentina’s default at the beginning of the century.

Most famously, Argentina issued a 100-year bond last year. Macri had also started to implement much needed economic reform. The recent episode is unlikely to have gone down well with Argentinians. Many still feel aggrieved from the last time the IMF intervened in the country in the early 2000s. Macri is up for re-election next year. Without a turnaround in fortunes for Argentina, a win for Marci is not looking good – cue the autocrat?

Turkey, who has an autocrat at the helm, is equally feeling the pain of US dollar strength. The stronger US dollar has not helped Turkey, with its large current account deficit reliant of foreign debt. But President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has not helping matters either. In a country experiencing rapidly rising inflation, the last thing a leader should say, within an earshot of financial markets, is that interest rates are the “mother and father of all evil” and should be lowered. This approach goes against monetary policy orthodoxy and in the case of Turkey certainly spooked the horses. Like the peso the Turkish lira has also more than halved against the US dollar this year.

4 Comments

...and who can forget the Thirsty Camel Crisis (1 part vodka, 2 parts dry ginger; from memory, of course!), when Dubai melted down and had to be bailed out by its neighbours. And that, arguably, morphed into the GFC.

The 100 year bond issue by Argentina was oversubscribed. I was thinking at the time that whoever pushed the button on that idea doesn't know Argentina's financial history.

Fantastic article, well explained

Thanks Jeremy. The article has partly restored my faith in Kiwibank. At least somebody there has half a clue as to what's going on in the world. So, where does that leave interest rates this time next year?

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.