Late last year, the Finance Minister, Nicola Willis, suggested that the charities area was ripe for some tax reform. She expressed concern that the exemption for charities business profits could be being exploited. The sector has nearly 8000 entities, which apparently report a total of over $36 billion of gross income with potential taxable profits of $1.56 billion annually. Now, in theory, those profits would represent over $400 million of tax revenue if the exemption was removed in full. Given the Government's current straitened circumstances $400 million is not an insignificant sum.

Inland Revenue subsequently issued a consultation document on the topic in late February which closed on 31st March. The consultation sparked quite a bit of concern throughout the charity sector although the main concerns under consultation appeared to be about large organisations making use of the business exemption and donor-controlled charities.

In April, following the end of the consultation period, it became clear from the Finance Minister that in fact, contrary to what was anticipated, there wouldn't be any budget reforms for the charity sector contained in this year's budget.

Matt Nippert, the redoubtable business investigations reporter for the New Zealand Herald, filed various Official Information Act requests to get more background on what happened in that consultation process, and an understanding of why the Government might have changed its mind, and he published a story in the New Zealand Herald last Monday.

Sector push back

In essence, the sector unsurprisingly pushed back very significantly with 901 submissions received, which is actually a significant number given there are about 8,000 charities in the sector. 86% of those responding were opposed to removing the charity business tax exemption.

Incidentally, as part of the process, Inland Revenue met with 14 large charities and sector groups as part of the consultation. This is actually quite standard when Inland Revenue is doing consultation. It does go out to interested sector groups and discusses proposals. There can be arguments as to whether or not this borders on lobbying, but it's a part of the Generic Tax Policy Process and it gives Inland Revenue a boots on the ground insight on its proposals. What was actually discussed at those meetings won't be released under the Official Information Act request, although the formal submissions on the consultation will be published in due course.

There were complaints it was a very short period of consultation. And obviously there were big concerns about the potential implications for many charities if the exemption was removed in terms of compliance costs and funding. Quite a few people responded that it might be better if Inland Revenue and the charity service focused on the bad actors within the system, rather than taking a blanket approach.

It also became clear following consultation that the possible tax gains from reforms were nowhere near the suggested amount, in fact, were more likely to be around $50 million per annum. As Matt Nippert explained the sector is quite fragmented, with a huge pool of tiny operators and then a very small pool of huge operators such as Sanitarium. Inland Revenue’s proposals would probably have left at least 85% of the organisations untouched.

“A bit scattershot”

Speaking to Matt Nippert KPMG principal Darshana Elwela remarked the Inland Revenue proposals were “a bit scattershot and there was in our view a bit of incoherence about what the potential problem was and how it was being proposed to be fixed.”

I think with Darshana’s comment, sometimes we've seen Inland Revenue propose something and it's not exactly clear the extent of the issue to be resolved, the only references involving subjective word like “significant” without an explanation as to how much represents "significant ".

The other interesting feedback I saw reported by Matt Nippert is that in relation to the potential issue around donor-controlled charities - which I think is a concern - only 46% of respondents opposed a mandatory minimum for distributions for such entities.

I thought that was very surprising because the issue around donor-controlled entities is whether in fact they're making donations or using the funds appropriately for charitable purposes. Darshana Elwela of KPMG also touched on this, commenting

“Transactions between the donor and the charity could result in the more favourable tax profile for the tax paying side. There were some genuine concerns some of that might be happening.

"The question we had does raise a wider question as to whether these entities should be charities to begin with.”

“A lot of complexity”

Willis denied there has been an about-face, commenting “There is a lot of complexity involved with designing new rules so as to ensure they have integrity and are simple to understand. Therefore, the Government has asked Inland Revenue to do more work on the options.”

The end result is Inland Revenue has gone away to think again because, as the Finance Minister’s office noted, “the Government is focused on fairness and integrity of the tax system. It is important that any changes be the right one, so it's going to take the time needed to get it right.” In short, watch this space.

Rich List re-ignites the wealth tax debate

Moving on, this week saw the publication of the National Business Review’s annual rich list for 2025, and it showed that for the first time ever, the country's wealthiest people are collectively worth more than $100 billion. That's up nearly $7 billion from last year and the criteria now to be included in the rich list is over $100 million of estimated net worth.

It should be said, establishing the wealth of our richest is often educated guesswork, to be frank. That’s because unlisted companies often form the core of the wealth of many of the wealthiest families and persons on the rich list.

By contrast, overall, in 2024 the net worth of all households declined by over $4 billion. Infometrics’ chief forecaster Gareth Kiernan said that average household wealth had fallen since the end of 2021, but that was unsurprising because housing makes up more than half of household assets, and house prices remain below their 2021 peak.

That is the knock-on effect for the average person in New Zealand. And just this week councils have been releasing their rating valuations, and they are showing declines too.

By contrast, the super wealthy have very much more diversified portfolios, so the core of their wealth is actually held in businesses and not so concentrated in property. There are some property magnates in that group, of course, but you'll find highly diversified wealth, and wealth generates wealth and Thomas Piketty’s famous r > g formula from his monumental Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Time for a wealth tax?

The publication of the Rich List prompted Chlöe Swarbrick of the Green Party to set out the Green Party’s Budget proposal for a fairly chunky wealth tax of 2.5%. In theory it all sounds very attractive, but as we've just discussed beforehand, the valuation issues are far trickier than people anticipate in this area, particularly when you have large numbers of unlisted companies in the mix.

And then there is the real risk of capital flight. And as I've said before, in our case, I think it's significantly bigger than people might imagine because moving to Australia is very common and Australia has the temporary residence exemption, which is highly tax favourable. It would mean that, for most Kiwis moving to Australia, their non-Australian assets would not be subject to Australian capital gains taxes unless they became Australian citizens.

Tax is politics and why New Zealand is unique

The key thing to be kept in mind in the debate around wealth tax, and with all debates around taxes, is that what is taxed is entirely a political decision. So, the wealth tax yay or nay debate is going to be resolved at the ballot box ultimately. What is interesting at the moment is that other accountants are reporting they are getting queries from clients concerned about what they could do about a wealth tax if it happened. What are the options around that? This is interesting because it may reveal a shift in thinking that something might be happening. The debate seems to have heated up with growing concerns about inequality and record numbers of people applying for benefits.

In terms of wealth taxes, the classic wealth tax that's being described by the Greens is basically an annual charge on all wealth. It's well known that New Zealand does not have a general capital gains tax, but what really makes us unique relative to other countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is we don't have an estate tax, we don't have a gift tax, we don't have land tax (other than rates), and we don't have stamp duties (which, although they're transfer taxes, are effectively also a tax on wealth, being the value of the land at the time of transfer).

We've none of these taxes. But they used to be quite a significant part of the tax base. Back in 1949 such taxes represented 5% of all government revenue at the time, which would be $6 billion now, a very significant sum.

The absence of these taxes and any real form of capital taxation is putting pressure on the tax system to respond to growing pressures on funding. The calls are coming in for variations on some form of capital taxation, whether it's a capital gains tax, a wealth tax or potentially an estate tax.

We are, as I said, an outlier with the absence of capital taxes, but ultimately tax is political. The arguments will be decided by the electorate and politicians taking a stance and running on tax reform in the future.

New Inland Revenue kilometre rates come with a change in approach

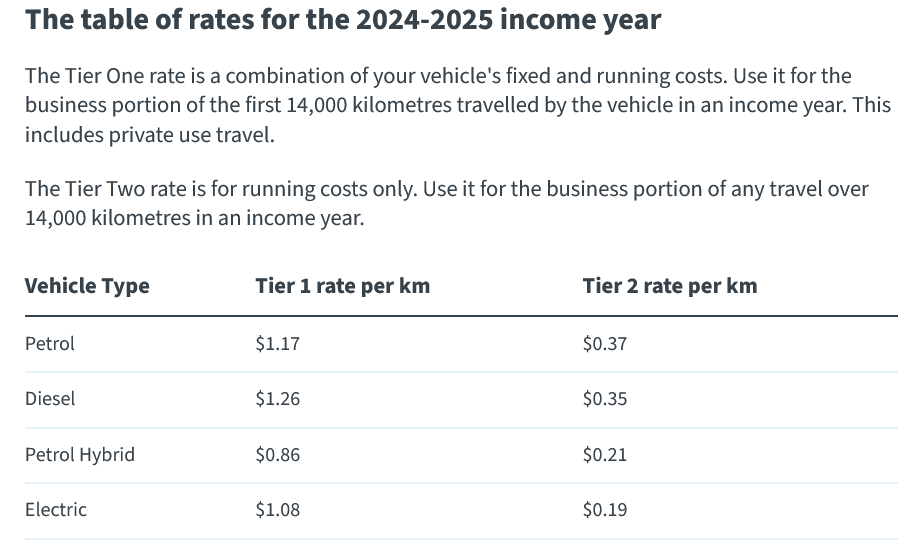

On more mundane matters. Inland Revenue has published its annual rates for business motor vehicle expenditure claims for the 2024/25 income year. You might think well, it's a little late after the event, but that's by the by.

What makes these rates different this year is that, as Inland Revenue explained, traditionally the Commissioner has set a single Tier One rate. However, due to the significant difference in vehicle running costs between the different vehicle types (Petrol, Diesel, Petrol Hybrid and Electric), a Tier One rate has been set for each vehicle category - being petrol, diesel, petrol/ hybrid and electric - to ensure the rates accurately reflect reasonable expenditure related to the business use of that particular vehicle

The new approach may mean that you have to make adjustments to your mileage reimbursement processes going forward.

Inland Revenue performance targets

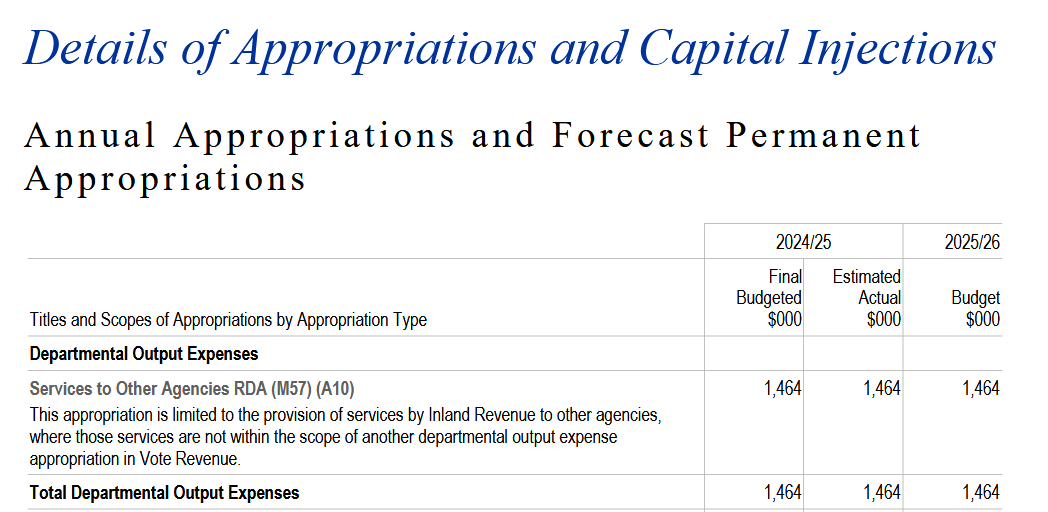

Finally this week, as part of the Budget, every government produces detailed breakdowns of spending for each ‘Appropriation’ or ‘Vote’ to be approved by Parliament as part of the Budget process. Reviewing the Vote Revenue Appropriation gives some useful guidance and detail about what specifically Inland Revenue is expected to do.

These appropriations are incredibly detailed. The Vote Revenue appropriation revenue runs to 40 odd pages setting out the various items of expenditure and what is to be spent or appropriated.

What's also of interest are the performance criteria for each sub-part of the overall appropriation including a summary of what is intended to be achieved by the appropriation, and how performance will be assessed. Now, not every appropriation line item has an investment. Some get an exemption under the Public Finance Act.

Tax payments & debt collection

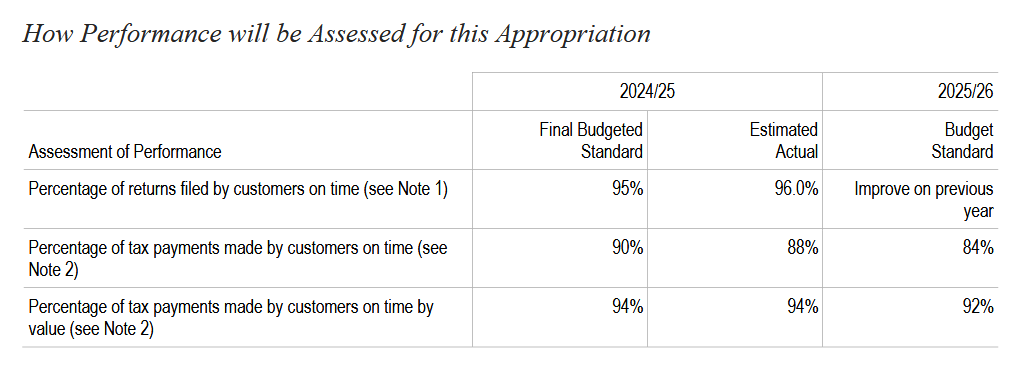

As can be seen the performance expectation for tax payments made on time for the current year to June 2025 is 90% but for next year it’s expected to be 84% maybe reflecting harder conditions in the economy are expected.

We've recently discussed the issue of student loans and overseas based student loan borrowers. Inland Revenue has a new expectation that 31% to 35% of all such borrowers will be making payments or meeting their obligations in the 2025-26 year. The percentage of collectable debt that's going to be over two years old is estimated for the current year to stand at 35.3% but is expected to be 40% or less going forward.

In other interesting snippets the percentage of litigation judgements found in favour of the Commissioner is expected to be 75%. The actual is running at 90%, and as we regularly report, there is a whole series of cases coming through where criminal prosecutions have been successfully taken by Inland Revenue.

How long to answer a call?

Now, how long does it take Inland Revenue to answer a telephone call? Well, the budgeted standard they try to meet is currently 4 minutes, 30 seconds or less. At present they're managing 3 minutes 8 seconds, which is very good. And next year the standard is again set at 4 minutes 30 seconds.

So, if you call Inland Revenue and you're waiting for more than 4 ½ minutes, it has not met its expectations. In fairness, just remember, this is currently the busiest time of year for Inland Revenue as they process the March 2025 tax returns for over two million people. The chances are if you do find yourself waiting for more than 4 ½ minutes, you won't be the only one.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā.

13 Comments

"...we don't have an estate tax, we don't have a gift tax, we don't have land tax (other than rates), we don't have stamp duties, which although are transfer taxes, are effectively also a tax on wealth being the value of the land at the time of transfer.

We've none of these taxes. But they used to be quite a significant part of the tax base."

And they were a significant disincentive to NZs economic efficiency, effectiveness & effort (also in the days of 67% income tax rates & Queensland advertising "no death duties"). Getting rid of them was part of the electoral mandate quid pro quo for the original introduction of GST (thanks Roger).

kiwikidsnz,

The UK has CGT, an Inheritance Tax(IT) and stamp Duty. Are we then measurably wealthier than the UK? If not, why not? If you think we are, what is your evidence?

Why are we an outlier globally on CGT?

We're certainly not poorer

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_wealth_per_adult

& also compare more or less equally to UK in both median income & GDP per capita

So, please explain why we should reintroduce envy taxes just because the UK has them

Can you please clarify what makes a tax an 'envy tax'? Income tax seems to fit the bill nicely, but you never seem to refer to it as an envy tax - I pay more income tax than the average earner, must be due to envy.

Perhaps it's a meaningless phrase that shows your arguments to be more emotional than logical?

I have previously referred to progressive income tax regimes as unfair & motivated by envy. Proportional /flat income tax rates are fair.

I wonder, how do you discern the emotions of the Government when it enacts tax policy?

I think it's very reasonable to have lower taxes on the first X dollars of income earned - to reflect the fact that everyone needs a certain amount of money to live a reasonably dignified life. The UK tax-free allowance seems fair to me.

Not driven by envy, driven by acknowledging that even lower income earners are human and have the same basic needs as I do. That extra dollar that I earn to pay for an overseas holiday is less important to me than the dollar earned by someone who needs it to feed their family.

If you want to go deeper, perhaps it's driven by fear of what happens when the general population gets stretched too far? Envy doesn't have to enter the picture.

Sure, then give everyone the same tax free income threshold.

Yes, I'd expect that to be the case.

"envy taxes" . Envy has nothing to do with it, but fairness certainly comes into the equation. NZ taxes only income but not capital, while almost every other country taxes both.

If you don't like the UK as an example, what about the Nordic countries?

You pointed to the UK example & I responded with evidence that demonstrated that your supposition that envy taxes make people wealthier was incorrect (evidence that you could have easily found yourself). I'm not interested in playing sealioning games.

All of these taxes, and lack of tax on capital, allowed NZ to invest in significant national infrastructure to gain efficiency over the long term, allow a greater standard of living, and the removal o the, has benefitted those most who began working in the 60's-70's given the lowering of taxes across the lifetime which I doubt we will ever see again. This is precisely why we now have the wealthiest generation coming to retirement, an the rets of the working population be9ing told they will have to pay more and more as a reality in order to maintain our current status quo pension scheme, healthcare etc. Everyone wants the best of everything, but nobody seems to want to pay for it.

A 'significant disincentive to economic efficiency' ??? Citation needed!!

So charities don't pay income tax, are they registered for GST? If they currently are able to claim GST deduction them removing that would be an obvious and easy way to tax them.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.