By Bill Kaye-Blake and Prince Siddharth at NZIER. This is a re-post of an NZIER Insight and is here with permission.

The sector seems to be holding up

The New Zealand agri-food system seems to have performed well through the COVID pandemic and various alert levels. There were some hiccoughs – queues in Level 4 when the number of shoppers was restricted, some panic buying and rationing – but we didn’t see weeks of empty shelves.

Export revenues are up, too.1 Dairy and fruit exports have been up, and meat exports increased slightly. Some products aren’t doing as well, such as seafood, but on balance our food exports are higher. As MPI noted, the weaker New Zealand dollar has helped support the overall sector.2

Domestically and internationally, sales look good for the agri-food sector. But how do people in the sector feel about the pandemic and restrictions? And what happens next? We surveyed a combination of farmers and non-farmers in the sector to find out.

Export focused, with a domestic component

In New Zealand, the agri-food system has two key functions. One, it provides large amounts of dairy products, meat, wine, fruit and some other commodities to overseas markets. Some 95 percent of dairy production is exported, as is most of the country’s red meat production. Two, the system also provides the food we eat. About threequarters of the domestic food supply is grown here,3 and distribution and retail activities get food to consumers.

For economists, the agri-food system has some key characteristics.

• Food is a necessity. Demand for food is fairly stable and not especially sensitive to prices. As we have seen during the pandemic, people still need to eat even if prices go up.

• Production of raw materials – the stuff that comes off farms and orchards – is inflexible in the short term. Orchards have only so many trees; farms have only so many animals. They cannot quickly change the amount or range of their production significantly.

• A lot of raw materials and some final products are perishable. Their value can fall very quickly if they don’t get to market. Processing can add storability to food products, which increases flexibility for getting products to consumers. Liquid milk, for example, needs to be refrigerated and consumed in a week or so. Milk powder, on the other, can be stored for months.

It adds up to a sector that is more inflexible than other parts of the economy. However, these characteristics don’t tell us how the agri-food system should cope with the pandemic. It is an essential sector producing a necessary product, so it should do well. On the other hand, supply chain disruptions, problems accessing overseas markets and inflexibility could harm the sector.

We asked farms and businesses in the sector about their experiences. What we found is that many in the sector feel squeezed between the market disruptions and higher costs. Since farms in particular are not flexible in the short term, they have just had to absorb the impacts.

Worryingly, a lot of people in the sector think the situation will continue for a while yet. If it does, that could mean more pain in the sector in the future, and possibly higher food prices.

Higher costs, lower prices

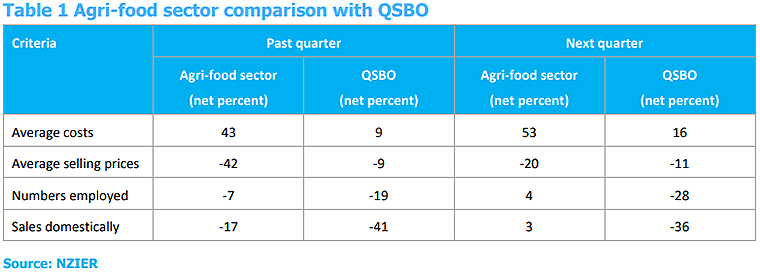

We wanted to gauge sentiment in the agri-food system. NZIER already runs a survey, the Quarterly Survey of Business Opinion (QSBO), which doesn’t include agriculture or related businesses. We decided to compare sentiment in the agri-food sector with our QSBO results.

A comparison between the agri-food sector and the recent QSBO is shown in Table 1. The figures represent net sentiment – the percentage of positive response less the percentage of negative responses.

For costs and selling prices, the results are dramatically different. Agri-food respondents felt that their costs were up but the prices they receive are down, just like the QSBO. However, the agrifood net percent figures are more extreme than the QSBO results. This result has some theoretical backing. Food prices move up and down a lot. Small changes in the demand for food tend to create relatively large price changes – this is what economists call ‘price-inelastic demand’. If overall food consumption fell during the first half of the year, with restaurants closed and very few tourists in the country, we would expect a drop in prices.

At the same time, the lack of flexibility in agricultural production means that farmers don’t have a lot of room to make changes when costs rise. Instead, they just have to absorb the increase. For that reason, it isn’t surprising that a net 43 percent believe that costs have increased.

Finally, there is support for the idea of food-as-a-necessity. The QSBO found that a net 41 percent of respondents reported a fall in domestic sales. For the agri-food sector, that figure was better, at 17 percent.

We dug a little deeper. We examined the responses to these questions for people in the sheep, beef and dairy industries. The largest net negative for all three industries was for average selling prices. A net -75 percent in the beef industry, -66 percent in the sheep industry and -56 percent in the dairy industry reported lower selling prices.

By contrast, the other respondents – from horticulture, arable, chicken, deer, etc. – reported a net positive for their selling prices of 3 percent. In fact, they were more positive for all the sales questions in the survey: average selling prices, domestic sales and international sales. One possible reason for the difference is that these industries are more connected to the domestic market and less focused on exports. However, the same pattern did not hold for production questions. For average costs, food loss and waste and overtime worked, the beef, sheep and dairy respondents had similar responses to everyone else.

Concern about risks, international links

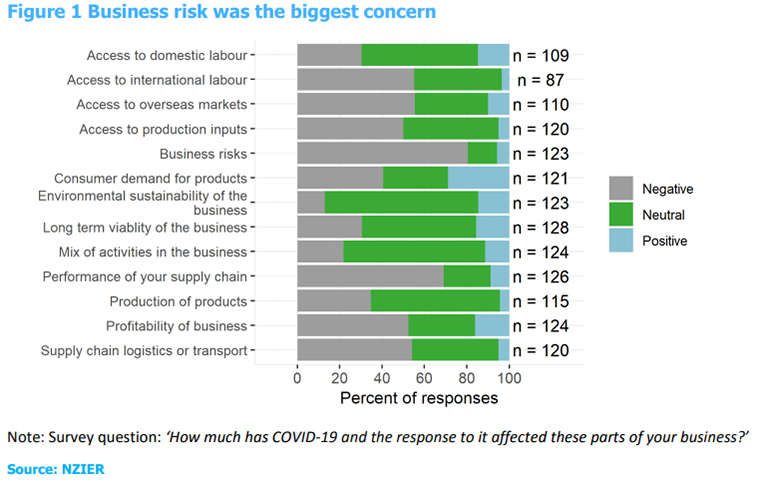

We asked respondents about impacts on specific parts of their operations, such as labour, supply chains and consumer demand. The results are shown in Figure 1. The net percent of respondents is obtained by subtracting the number of respondents who selected ‘Very negatively’ or ‘Somewhat negatively’ from the number who selected ‘Very positively’ or ‘Somewhat positively’, and dividing the result by the number of respondents who indicated any impact (positive, neutral or negative): (positive - negative)/(positive + neutral + negative). Non-response and ‘N/A’ were not included. Most commonly, respondents said that COVID-19 had not had an impact. Other results to note:

• Negative responses outnumbered positive ones; the net negative across the sample was -31.5 percent.

• All aspects of operations had net negative responses except environmental sustainability, which had a slight net positive impact.

• The largest net negative was for business risk, at -74.8 percent. Other highly negative areas were performance of supply chains, access to international labour and supply chain logistics or transport.

The result about business risks carries through the whole survey. We didn’t dig into what the respondents were thinking, so we don’t know what they included in this category.

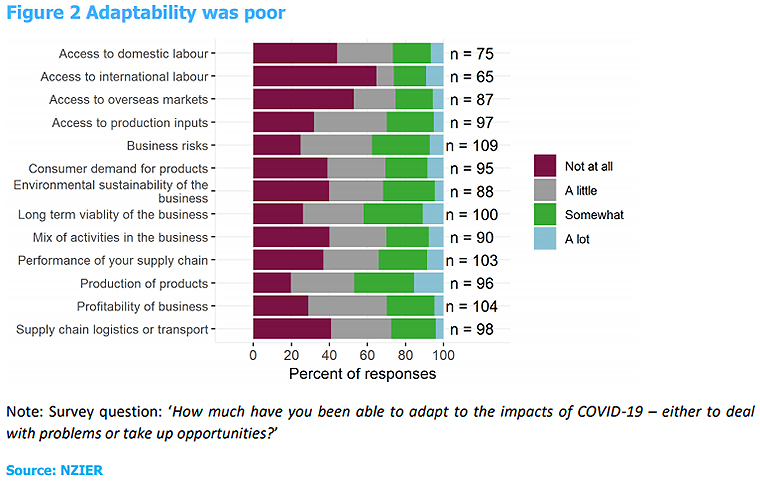

However, no one knows what’s going to happen next, with the pandemic, international trade, domestic conditions, etc. It is harder to plan given the unknowns. It may be that the unknowability is preying on the minds of people in the agri-food system, especially given the structural inflexibilities described before. It may just be an indicator of generalised anxiety. Respondents confirmed that they perceived a lack of flexibility. We asked them how much they felt they were able to adapt to COVID-19 (Figure 2). They reported that they were not able to adapt much or at all for most aspects of their operations. As shown, though, there was variation in where respondents felt they could adapt.

Non-farmers and farmers reported different experiences

We checked for differences between farmers and non-farmers. In theory, on-farm production is less flexible than other parts of the agri-food system.

We found that farmers, on average, felt a greater negative impact than other respondents. Farmers reported a net negative impact of -40.4 percent while other respondents reported a net negative impact of -12.2 percent. For both farmers and other respondents, business risk stood out as having the greatest negative impact. Across the other aspects of operations, a greater proportion of the other respondents reported positive impacts than farmers. In fact, non-farmer respondents believed that COVID-19 had a net positive impact for environmental sustainability (27.8 percent), consumer demand for products (14.3 percent) and access to domestic labour (10.7 percent). Nonfarmers adapted to COVID-19 more than farmers. Across most aspects of operations, a greater proportion of the non-farmer respondents were able to adapt ‘a lot’ than farmers. There was a lower proportion of the non-farmer respondents who were unable to adapt at all compared to farmers.

Things will get better...

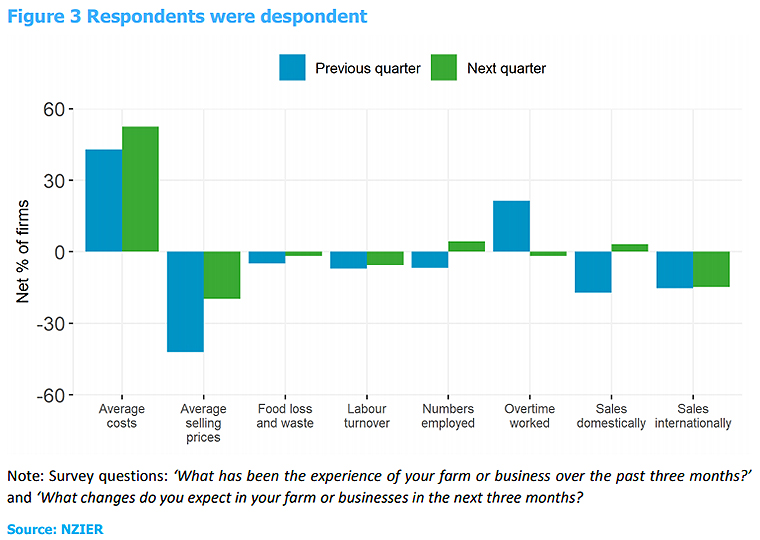

We asked people about the future – what impacts they expected from COVID-19. In the short term, compared to the previous three months, there is greater optimism regarding nearly all aspects in Figure 3. One exception is that increased costs are expected to carry over to the next quarter. As well, the view on international sales remains essentially unchanged between the two quarters.

...but they won’t be the same

We asked respondents whether there would be a ‘new normal’ in two years’ time. A majority of them agreed that there would be. The next most common response was that the situation will not have settled down, while fewer people expressed a belief that things will go back to how they were. Non-farmer respondents were more likely to believe that there will be a ‘new normal’ in a couple of years, while farmers said that the situation will not have settled down.

Some of the responses from those who believe there to be a ‘new normal’ include:

• ‘Greater reliance on technology and changing workforces to designing automated processes rather than working in processes.’

• ‘Self distancing, not many supplies able to be obtained from overseas. More domestic market.’

• ‘Greater demand for environmentally sustainable product.’

The view of some respondents on supplying more to a domestic market aligns with our survey results of a net positive view on domestic sales, at least in the short term.

We also asked respondents how long they expect these impacts to last across different parts of their farms and businesses. Most people stated that impacts on business risk will last beyond two years. This view was common amongst those in the sheep, beef and dairy industries as well as among farmers and non-farmers.

The agri-food sector feels squeezed, which won’t stop soon

The economic explanation for the survey results is lack of flexibility. Food is a necessity, so prices are volatile and amounts consumed don’t change much. Farming requires planning and investment, so on-farm change tends to take time. When inflexible demand meets inflexible supply, the commercial fortunes of farmers can shift quickly.

In our Insight 90, NZIER found that agricultural exports (excluding forestry) went up by nearly $1 billion in 2020, compared to the same period in 2019, on the back of strong dairy exports.

The relatively negative survey results compared to actual export sales in the first half of 2020 raises questions. Did the survey attract respondents who were worried or pessimistic? Are their perceptions out of line with actual performance? Are gains and losses uneven across the agri-food sector? All these factors could be affecting the results.

People in the agri-food sector report feeling squeezed between lower prices and higher costs, which they expect to continue. If these perceptions are accurate, the sector is going to face some tough times. We may see some combination of higher consumer prices, changes in the sector and calls for government action to support the sector.

Notes:

1. NZIER. (2020). Land-based industries help see New Zealand through tough COVID times. Insight 90. Wellington. https://nzier.org.nz/static/media/filer_public/e0/2f/e02f3f0ca26f-4a0c-…

2. Ministry for Primary Industries. (2020). Economic update for the primary industries. Wellington, June. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/40808-economicupdate-for-the-primar…

3. Drew, J.M. (2018). Healthy & climate-friendly eating patterns for New Zealand. Thesis for Bachelor of Medical Science, University of Otago.

This Insight was written by Dr Bill Kaye-Blake and Prince Siddharth at NZIER and peer reviewed by Dr John Yeabsley, NZIER, September 2020. This NZIER Insight is here with permission.

5 Comments

I have not seen one farmer or one NZ company selling their products directly to Chinese consumers via DouYin (抖音, or Chinese Tik Tok).

I barely remember that A2 made an appearance on DouYin.

Hi Xingmowang-it would appear that doing buisness in China is difficult- just ask all Fonterra Shareholders who have lost the best part of 1 billion dollars since trying to form partnerships over the years-Sanlu,Beingmate,China Dairy Farms-all loss making investments,it is a serious case of once bitten trice shy

I can give you gazillions examples of foreign brands making tonnes of profit in China.

It is difficult to for anyone to do business in any foreign country per se.

The ultimate question and correct attitude is why cannot my business make a profit in China, and what is wrong with my strategy and doing?

Please start the list five at time will be fine.

Thanks

Our growth industries are still lagging behind global counterparts in tech adoption.

MYOB reported that one in five farm has not kept up with new technologies and our manufacturers are well-behind the IoT and IR4.0 curve.

The sectors, particularly manufacturing, often quote lack of investment on critical skill shortages for their failure to keep up with 'first-world' trends.

Immigration adding a lot more than 100k "skilled" workers to our population each year but we're not bringing the high-skilled messiahs who will work on low wages and help transform these struggling businesses to meet developed economy standards.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.