The news front the last week has been eventful; the Queen ‘passing on’, Ukraine kicking the Russians butts at least for now, and we have moved into a major ‘post pandemic’ stage with masks no longer mandatory in many situations.

However, since the positive turnaround of the last GDT not a lot has happened to highlight in the rural sector. So, it is timely to have a look and see what is occurring with rural debt.

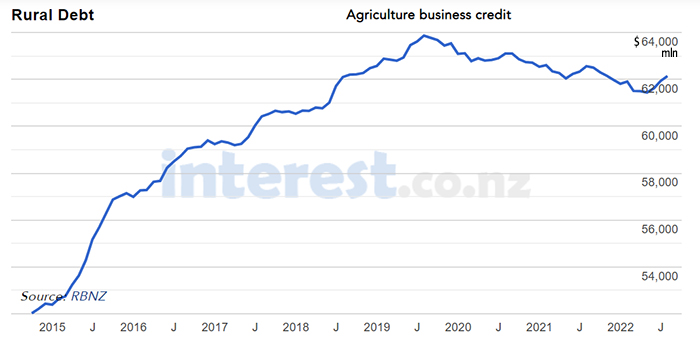

Looking at the interest.co.nz chart of Reserve Bank (RBNZ) data shows the trend over all agricultural sectors for the last seven years (and beyond) and for the last couple of years we can see a gentle decline (last 6 months it has reversed again).

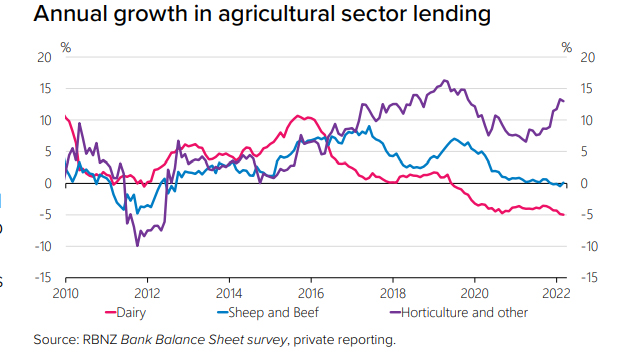

Looking at the RBNZ summary of the nation's debt and at the specific agricultural sectors makes a bit more interesting viewing, bearing in mind the graph here dates back to April numbers. It shows that while all agriculture has reduced borrowing in the last 3-plus years, the lift in the last 6 months is confined to the horticultural sector with dairy actually leading sheep and beef in their reduction in bank borrowing.

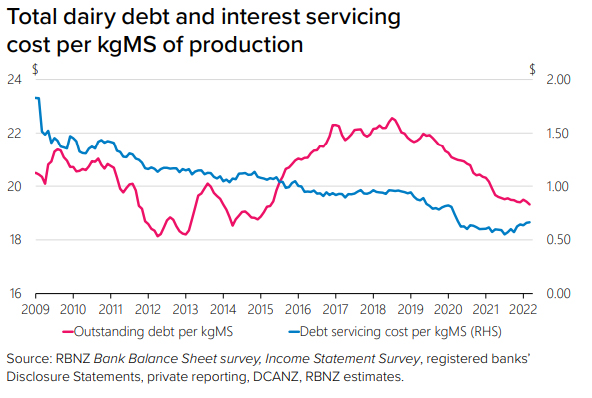

Two reasons why dairy borrowing and subsequent debt have reduced for dairy are:

- The greatly reduced number of dairy conversions that have occurred in the last 5 to 6 years due the constraints/regulations with water and nitrate emissions that are in place in many regions. Cow numbers have reduced by approximately 300,000 since ‘peak cow’ and the number of herds (farms) have also reduced with a reduction in the number of herds by 193 between the 2018/19 season and the 2019/20 season (farm size per hectare has increased from 139ha in 2010 to 155 in 2012 so amalgamations have been taking place although there was no change in the last couple of years.

- The second reason that lending has decreased is the better cashflow situation most dairy farmers have found themselves in with the lift in farmgate MS prices. An observation, now that costs per MS are now said to be running at about $8.18 how dairy farmers managed to stay profitable in the past either says something about the constraints they put on themselves then or how the purse strings have loosened up now (increases in interest rates aside), probably a bit of both.

| $/kgMS |

$4.65 |

$4.30 |

$6.52 |

$6.79 |

$6.35 |

$7.19 |

$7.74 |

$9.50 |

|

Year |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

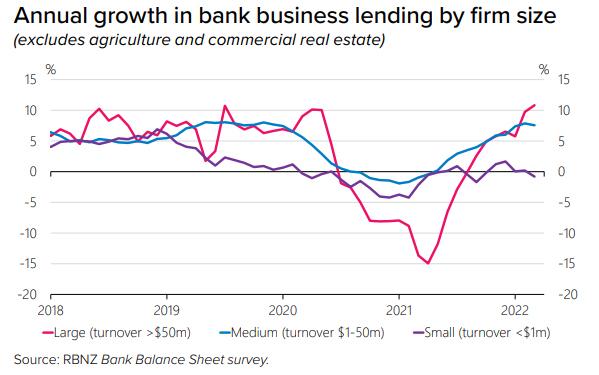

When comparing the above graphs to what is happening in the non-agricultural sectors the impact of the pandemic on the non-ag sector becomes glaringly obvious. Firms look to have retrenched initially to try and ride out the impacts and then perhaps when it became obvious the pandemic was not going to be an overnight phenomenon made up for lost time with a steep return back to more normal patterns.

The lack of any real movement either way by the SME’s (<$1m turnover) perhaps reflects the difficulty this sector can have in getting loans and also shows why productivity for this segment of the economy has been very low, for a supposed lack of investment in new technologies - perhaps showing a business would rather fold with a small debt than a large one.

Sheep and beef farming have been generally reducing debt with a similar pattern to dairy but at lesser levels, which given the record prices being achieved for most red meat products is perhaps a little surprising it hasn’t been at greater levels. It may reflect the poor contribution wool continues to make to the farm balance sheet and the fact that at any one time there is often a region affected by drought.

There is generally a greater financial conservatism in the sheep and beef industry and also the older age of farm owners may also be a contributing factor. I.e. less time left in the industry to enjoy the fruits of new investments.

Looking to the future it may be that climate extremes are what are going to have as the greatest impact upon all sectors profitability and debt levels.

Product prices are likely to remain firm-to-good, but the great unknown will be the impact of climate. NIWA have been predicting a La Nina pattern for this coming summer. In my experience of East Coast farming this has been preferable to a El Nino pattern, with less chance of drought (except for the western and southern South Island) but of late it has been bringing with it heavy rain events and plenty of infrastructure damage requiring essential spending be-it by insurance companies, local and national government and the private individual, in this case farmers.

This could also mean that for consumers, vegetables and perhaps some fruit production may be affected, and prices may not enjoy the seasonal drop-off in prices that normally would be expected in the warmer months.

MPI obviously had some concerns in the pandemic about farm debt as the “Farm Debt Mediation Scheme” was introduced in July 2020 “designed to help financially distressed farmers by providing an independent, constructive and timely process for them to work through debt problems”. Farmers who decide to access the service share the costs with the finance provider(s) but only up to a $2,000 share with the maximum expected cost of mediation topped at $6,000. Given the financial strength of the rural economy at the moment it is not expected that there are many farmers using the scheme. However, even in good times financial woes can occur especially when climate extremes take place.

18 Comments

First - I struggle to see mine or my neighbour's costs being anywhere near $8, even with interest rates approaching 6%, if they were my bank manager would be pretty nervous and so would I.

There is a level of pessimism among many farmers, maybe a reflection of getter older or a lack of realistic succession opportunities? The paperwork is getting more and more onerous, political and public criticism of farming don't help.

Surprising that beef and sheep debt hasn't fallen faster considering how many farms have been sold to forestry. Maybe will show up over the next couple of years or the farms being sold have been held longer and have less debt.

My advisor say despite record milk, beef and lamb prices that farm values, other than for forestry, will be similar to last season and the banks are supportive but not exuberant..

Wilco I think your comments are on the button , the view from my client base is “”why am I continuing to work so hard and trying to cope with endless new regulation while producing cheap food for an ungrateful populous””

I think it was Rabobank , from memory , had an average cost of around $ 5.20 , quite recently.

Average costs quoted vary depending on what is included, the $5.20 number would probably be before tax, interest, capital expense, depreciation and drawings, add those and most are heading for $8.00

Many hill country farms struggle with succession. Some have no one really interested in taking over and others have problems with financing one person as the siblings want their cut and mum and dad need funds for their retirement.

It becomes a vicious circle of debt from one generation to the next.

Sadly, there is a lot of ungrateful people in our culture these days, and by far the worst of them are the poor people who have no idea just how lucky they really are.

Wrong,

"Sadly, there is a lot of ungrateful people in our culture these days, and by far the worst of them are the poor people who have no idea just how lucky they really are."

I would like to think that there is a heavy dose of irony in there, but I'm not convinced there is.

Were they ungrateful, disenfranchised or something else?

I recently listened to a wealth factory owner describing his staff as slaves and wondered how they would describe the situation they find themselves in

Its interesting how people's expectations and experiences change the way they act and talk about these situations

It's not rocket science that lending is lowering . Dairy was the only show in town , and now that outside forces have stopped this there's not much else happening . Sheep beef and even cropping just aren't bankable at land values on average around $2000/su (Southland) . We are entering a period of stagnation . Farm succession is only viable if all of the family really want it to happen.

I'm guessing hort borrowing was driven by the kiwi fruit fomo , pretty sure this has run its course.

A few investors/buyers of cherry orchards in the last few years, may be rueing they ever invested/bought. Very difficult to have made money in the last few years unless you were managing the orchard yourself. I heard recently of an intergenerational orchard been sold after 3/4 tough years. There's a wall of cherries coming on in the next few years due to some very large syndicates getting in to the industry - assuming they can get the staff they need to pick it. It's all very well talking of export prices but the reality is that you don't get an export only crop - and the domestic market can only take so many, before the weight of sheer volume coming on to it is likely to collapse it. Meanwhile Chile is getting better at logistics and quality...Almost time to get out the popcorn.......

Dairy farms have the ability to repay debt under most situations. Sheep and beef on the other hand struggle. It all comes down to profitability. A large % of sheep/beef farms carry low debt ( maybe older farmers or well established generational family farms), and probably have little benifit in reducing a small mortgage. The new entrants in sheep may have more borrowed, but even at "record meat prices" struggle to make substantial profits or reduce debt.

Fact of the matter is dairy in an average season will far outstrip "record returns" for sheep/beef for profit margins. Especially when you look at ROI

Your comment is a bit general yet generally it would be true. The top 20% sheep and beef farmers are doing quite well for themselves achieving ROI of 8-10%. I wonder if it has more to do with higher age of farmers and not the pathways into sheep and beef like the dairy industry.

Ever increasing land prices only encourages old farmers to sit on the land and live off the capital gains rather than efficient production of meat.

A good example is most of sheep and beef farmers haven’t even adopted rotational grazing yet

Re rotational grazing I find your comment a little hard to believe. I wonder if you mistake this for set stocking during lambing and calving. Or large hill country properties where sheep fencing is prohibitive so larger paddocks are the norm.

Having recently got back into breeding stock from solely fattening, one has to give up the rotation at times. I have lambed ewes finding their way through electric fences to all parts of the farm right now. Calved cows needing space, so I am looking at set stocking those. The danger of cows going into high feed levels from low one day to the next and inducing scours amongst calves from excess milk is too high. It also helps to have them spread out and not passing on bugs. Been there. Also bloat can be a major. If there is no water reticulation, no way of getting bloat oil into cattle, having ewes and lambs everywhere cleaning up the clover can save lives.

All very well to dis the set stocking but its an important management tool. Old farmers arent necessarily fools or lazy. Just smart.

That's right Belle, it is better to work smarter than harder. In fact we are pulling down fences on our hill country as the replacement costs are huge. In the end many are just mustering aids and most of the year the gates are open.

Over the years with experimenting different grazing systems we have adopted a shuffle system which involves shutting gates to clean up rank growth at certain times. The other thing I have learnt is to leave the stock alone as much as possible. It seems the bottom line stays the same and even better the less you interfere with breeding stock.

Thank you Hans. Its interesting what you are doing. I see Colin Armer is experimenting with deferred grazing. He leaves a large area ungrazed from roughly november to march/april, I spoke with one of his managers about it (65) he thought it worked well, but he felt the younger managers were really thrown by Colins whole low input system. With what is ahead of us, high input costs, and difficulties with replacement parts, finding ways to cope will have us all experimenting with lower inputs out of necessity.

Belle

These is nothing new about Deferred Grazing it’s been we’ll proven over time, just that most farmers like tractors and can’t resist mowing grass for some reason

Theres the thing, we all have our reasons for doing what we do and a dairy farmer would say topping and mowing makes for a better quality feed that will produce more milk solids. I would say it leads to pastures getting exhausted and having to regrass. But dairy can cover that cost. Or can it still? What we face going forward is bringing back many old school ways. Of which the discussion seems well under way. How do we pay our mortgages when our input costs are untenable. How do the highly geared manoevre their way through this big change? Are we worried about nothing? Will all this settle after a year or two such as in 2008? What will land prices be going forward? It is an unsettling time.

Yes agree on the age thing, although we are seeing in our area those people exiting now with the higher land prices. Pathways into dairy occur through it being more profitable. I dont know too many sheep and beef farmers that dont rotationally graze, except for lambing where ewes are set stocked to lamb in a natural way. Most sheep farmers do pretty well to extract as much out of thier systems as possible. Im not sure what the answer is to increasing our pasture based red meat production. It seems it has just been a steady refinement of the good systems developed in the 80's.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.