Halfway through the Year of Economic Growth, New Zealand’s ‘green shoots’ have yet to bloom and lower interest rates may not be enough to change that.

The Reserve Bank has cut its benchmark interest rate by 225 basis points over the past year, from 5.5% to 3.25%, but the main impact has been a lift in business confidence. Real activity remains weak across most sectors, with agriculture the exception thanks to strong commodity prices.

New Zealand appears to be undergoing what ANZ economists call an “underwhelming economic recovery”, and BNZ describes as “a mid-year wobble”. Recent surveys and labour data show little sign of momentum.

“There was a clear wobble in a whole range of indicators in May. But none more so than the Performance of Services & Manufacturing Indices. Their deeper decline into contractionary territory was not in ‘the recovery’ script,” BNZ wrote in a note.

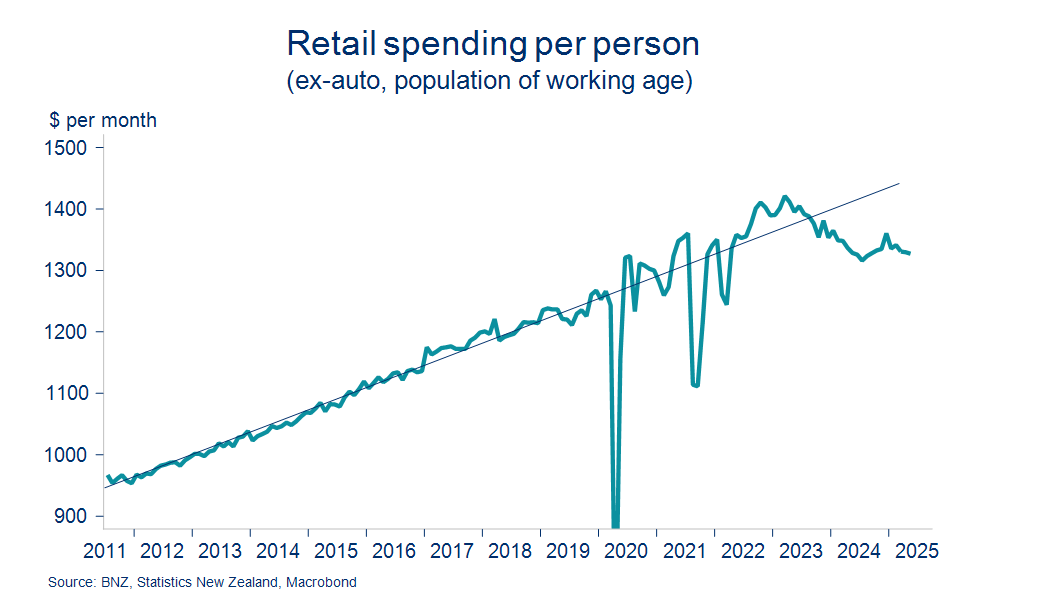

“The failure of retail spending to fire has a lot to do with the stuttering nature of the recovery … to even say spending is flat may be overstating the case.”

Card spending in May was no higher than in September 2022 and remained 6% below its 2023 peak on a per-person basis. Lower interest rates and improving confidence have yet to translate into stronger spending or consumer demand.

Stephen Toplis, head of market research at BNZ, says experimental Stats NZ data released on Thursday sheds light on why: overall, households are not better off with lower interest rates — in fact, they are worse off.

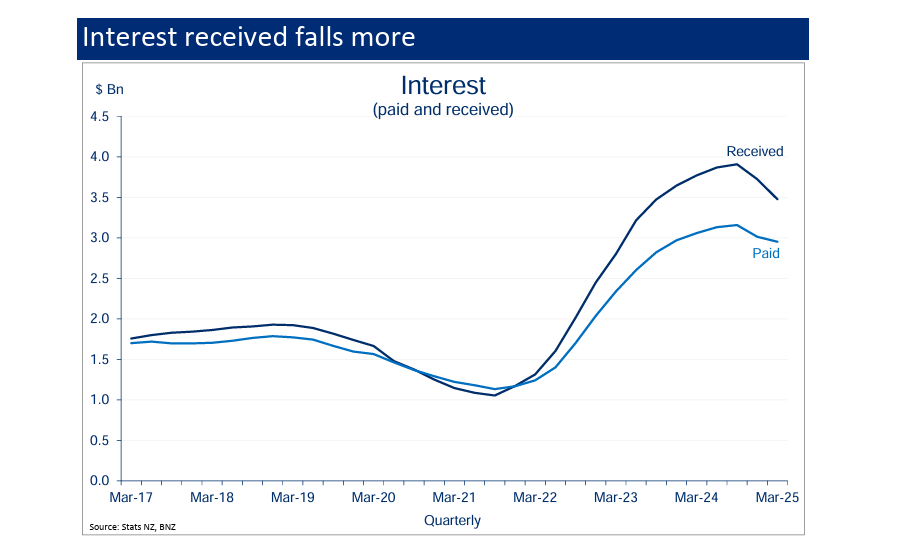

Falling mortgage rates are easing pressure on households with debt. Interest paid in the March quarter was down 3.5% on the same period a year earlier.

“But one shouldn’t forget there is a significant chunk of the population that doesn’t have any debt, many of whom rely on interest income for their day-to-day spending. Believe it or not, the income accruing to these folk has dropped by more than the reduction in the amount paid,” Toplis wrote in a note.

Lower rates aren’t always better

The net effect of falling mortgage and yield rates has been a drop in the total amount of money available for household spending, at least according to this data set.

Lower interest rates don’t automatically boost household spending, as they reduce income for those, particularly retirees, who rely on savings returns.

Toplis says households benefiting from lower interest rates are likely younger and more inclined to spend the extra cash, so the net effect on consumption may still be positive.

“[But] one should not necessarily assume falling interest rates will be sufficient to boost spending in the current environment,” he wrote.

Even if mortgage repayments drop, households may hesitate to spend the extra money while the labour market remains uncertain and asset prices stay flat.

Asset prices are one of the key channels through which monetary policy reaches the real economy. As values rise, households feel wealthier and are more willing to borrow and spend.

While property prices appear to have stabilised as rates have fallen, they show little sign of recovery. CoreLogic NZ said hedonic values rose just 0.2% in June, after twin 0.1% falls in April and May.

“With asset prices going nowhere fast it shouldn’t be a great surprise that household spending is doing likewise,” Toplis wrote.

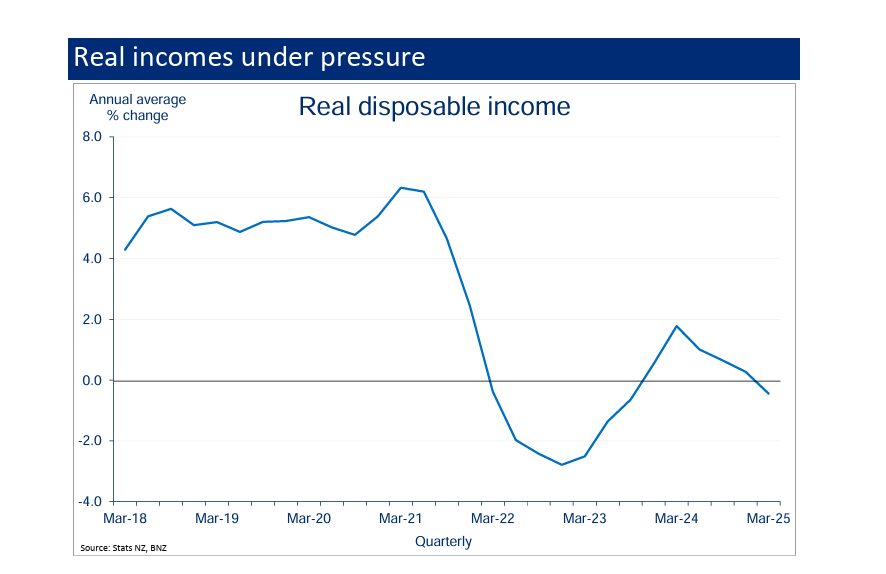

Stats NZ data shows household net wealth and real disposable incomes are flat or falling, and most of the excess savings built up during the pandemic have now been spent.

“Putting all this together, it becomes increasingly apparent just why the retail sector has been struggling … Monetary easing and the strong income gains accruing to New Zealand’s primary sector will support retail spending but these data are a salient reminder that we shouldn’t expect a resurgence in activity any time soon.”

Voter frustration

New Zealanders appear to be losing patience with the governing Coalition, which promised a stronger economy and cost-of-living relief. Inflation is under control and mortgage rates are falling, but households don’t seem to feel the benefit yet.

A research note by Infometrics said consumer prices are still rising, and now from a higher base. Prices in the March 2025 quarter were 23% higher than five years earlier.

Supermarkets selling 500 grams of butter for $8 to $10 does little to ease public concern about inflation, even if official data shows only modest price growth overall.

Add to that a sense of job insecurity, and many households don’t feel the economy is improving at all. Business confidence is surging, but employment confidence has hovered near Covid-lockdown lows all year.

Job site Seek said its Advertised Salary Index showed annual wage growth of just 2.3% in the year to June. That’s a little below the RBNZ’s inflation forecast of 2.6% over the same period.

If the Reserve Bank pauses rate cuts next week, it may frustrate households who feel the recovery hasn’t started yet. Economists still predict a strong recovery in the second half of the year, but rate cuts alone may not be enough to make that wish come true.

11 Comments

Interesting - I was thinking about a year ago and mentioned it in the comment section - especially noting the behaviours of many parties is been interacting with the past 5-10 years.

These people, with no mortgage debt, were reducing spending in the economy when rates fell, but then felt more optimistic and willing to spend as interest rates went up or were higher in the 22/23/24 time period. Now rates are dropping again they are cutting discretionary spending.

And my theory from that was that dropping rates may not actually stimulate the economy much - it may help those with excessive debt but what proportion of the economy is that? And should economic settings always be favoured towards those holding excessive debt? What about the many who have no debt but only savings? And who if you give them and adequate return for their savings are willing to spend that money on things other than more mortgage debt?

And my theory from that was that dropping rates may not actually stimulate the economy much - it may help those with excessive debt but what proportion of the economy is that? And should economic settings always be favoured towards those holding excessive debt? What about the many who have no debt but only savings?

It seems to be an assumption that given the opportunity, people will gorge on debt. And I personally think that's a fair assumption - it's consistent with what most people think as the 'right thing to do.' I'm personally interested in the whole appetite for debt. Given that most debt is issued for the Ponzi and consumption, at what point is that appetite satiated? Perhaps we just keep going up to a Minsky moment.

High levels of private debt accumulation are a central feature leading up to a Minsky moment as follows:

-

Extended periods of stability and optimism, encouraging more borrowing and risk-taking

-

Investors and firms increasingly rely on debt to finance speculative investments, expecting asset prices to keep rising

-

As private sector debt accumulates, the financial system becomes more fragile and vulnerable to shock

Well put. Let the system clear it self. Yes the rick takers will be bankrupt, but that was always included in the options.

Even second hand goods seem to achieving a lower % of new price then they did a while back, I am not sure its really increased depreciation or technical obsolescence, its a less competitive market for the item

People have pulled there heads in.

No kidding!

Anecdote 1: in May, I was doing due diligence on a potential business purchase, visiting Auckland's CBD on a number of occasions (not something I usually do). I recall a balmy late autumn Thursday evening where the streets, bars, restaurants were pumping and heaving with people. Not at all what I expected, but I was pleasantly surprised. Though there were scattered homeless people to walk around, here and there.

Anecdote/example 2: a business serving the domestic economy, purchased mid-2022. 60% growth over 15 months to end Q3 2023. Excellent, we're geniuses! Followed by 20% fall to end 2024. Oh, f@$k! A pick-up again, 10% growth Jan-Apr 2025, yes, we've turned the corner! Followed by flat/decline in May & Jun 2025. Oh, b$gg#r again.

Things are pretty mixed out there, middling, insipid.

Ohhh poor boomers... 🎻😢

We have to remember that 2008 was the last financial hiccup int he housing ponzi where prices actually went down. For many, the last couple of years goes against everything they were told their whole lives and we are not seeing the standard cycle play out as previously for a recovery given the deglobalisation, share market roller coaster, and high price of goods and services. Many, even boomers included, see uncertainty as there is too much at play currently to be able to feel comfortable predicting a recovery trajectory and making decisions accordingly. Until there is greater certainty, I can't say we will see much change. We will recover economically of course, but the timeline is shaky at best when factoring in historical downturns.

Business confidence is surging, but employment confidence has hovered near Covid-lockdown lows all year.

I work in the wholesale/B2B space and not one of my customers has given any indication of surging business confidence. Most are struggling with demand based on needs spending and nothing more. Business confidence surveys are no better than political polls.

As I have said many times on here, households have been net beneficiaries of higher rates. Also, the actual amount of interest paid on mortgages is still sky high because the effective mortgage rates has been very slow to come down and households have carried on taking on bigger mortgages.

I need to take issue with the paragraph on the housing 'wealth effect' though Dan. When total mortgages outstanding increase, this creates real new cash for sellers (and debt for mortgagors). In the last year, totalmortgages outstanding have increased by $17bn. That is $17bn of freshly created money in the accounts of sellers. Our economy is fuelled by that credit, not by vibes.

You are right, it is spending/borrowing which drives activity. The wealth effect just encourages people to do more of those things.

I've had to do grocery and fresh vege shopping in the last two weeks. The last time I did that was the previous year. I have the perception that prices have gone up at least 25% over the year. Less disposable income for the nice to haves.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.