In trying to think of a title that captured the essence of 2025, the expression that stuck to me and wouldn't leave me alone was: 'The Year of Blurrrgh'.

And, no that's not very eloquent. But it does seem to fit.

You may or may not recall, but in the run-up to this year, a number of economists and commentator-types championed the phrase "survive to 25" - meaning that if we could all get through the tribulations of a difficult 2024 then we would enjoy better things in the next year, IE 2025.

But as ANZ chief economist Sharon Zollner recently quipped, "survive to 25 just turned into survive 25", which neatly describes how the year now nearly finished didn't quite live up to the expectations of some.

It's probably fair to say a reasonable number of economists and commentators were expecting that those wildly over-referenced 'green shoots' would by now be giving way to flowers. Instead we are all still rummaging around in our gardens looking for the shoots and some of us think we can see them coming now. Just don't tread on them.

What exactly happened this year?

Well, in my preview of 2025, I said, among many things, this:

Normally recessions come from some naturally occurring blow to the economy. The recession we’ve just had was engineered by the Reserve Bank (RBNZ). Does that mean it’s easier to fix?

The psychological impact of the interest rate reductions so far has seen a big improvement in the mood of the country. Business and consumer surveys are showing much greater confidence.

However, I think a still unanswered question is how much lasting damage has been done by the high interest rates. A concern throughout the 2021-23 Official Cash Rate (OCR) hiking cycle was always that people may have been doing it tougher than they let on.

It’s still possible therefore that the RBNZ ‘overcooked’ the rate hikes and the damage is greater than we might like to think.

Confidence can be brittle and easily knocked. So, it is still by no means clear that the upticks we are seeing in intended activity - as expressed, for example in business surveys - will convert to actual activity as 2025 progresses.

In trying to explain just what has happened in 2025 I'm certainly standing by those comments I made a year ago.

To highlight the main points in the economy in the past year, I give you some cold, hard, data, by quarter and including figures from the end of last year if those figures were announced during the course of 2025.

Here's the economic big three:

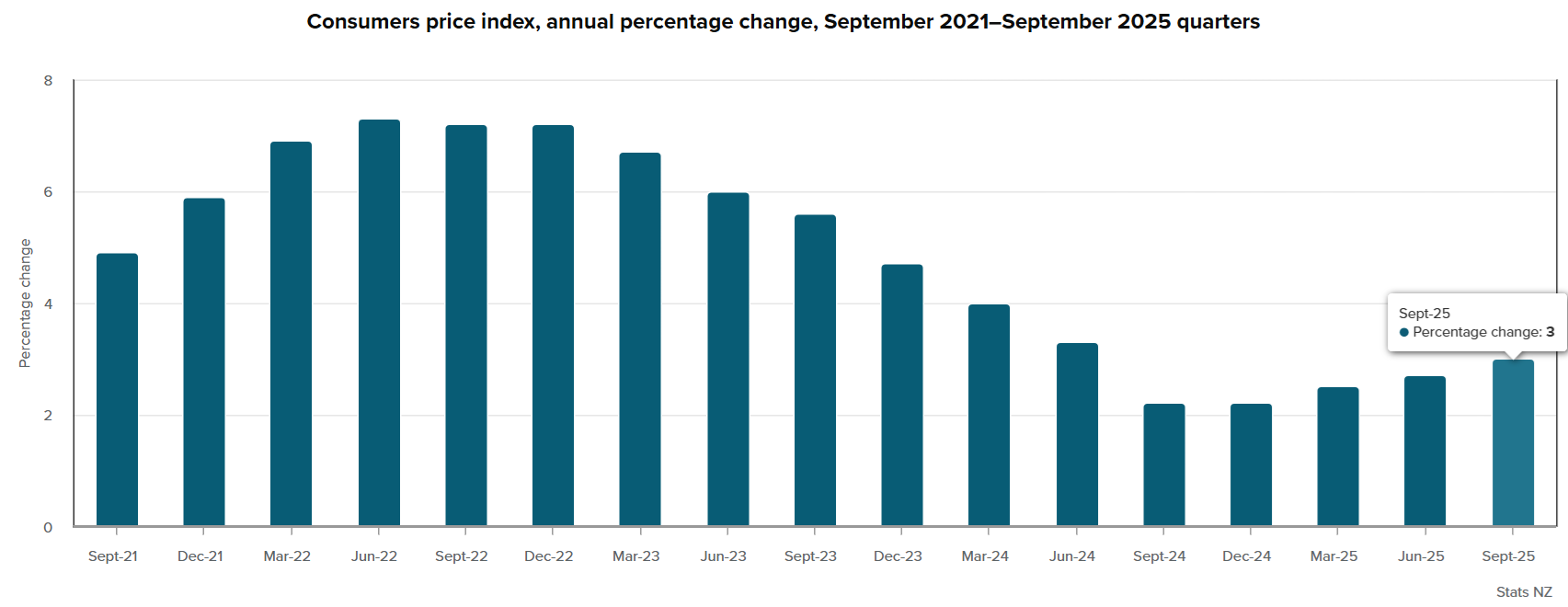

•The annual rate of inflation as measured by the Consumers Price Index (CPI) was 2.2% as of the December 2024 quarter, rising to 2.5%, in the March 2025 quarter, 2.7% in the June quarter and 3.0% in the September quarter.

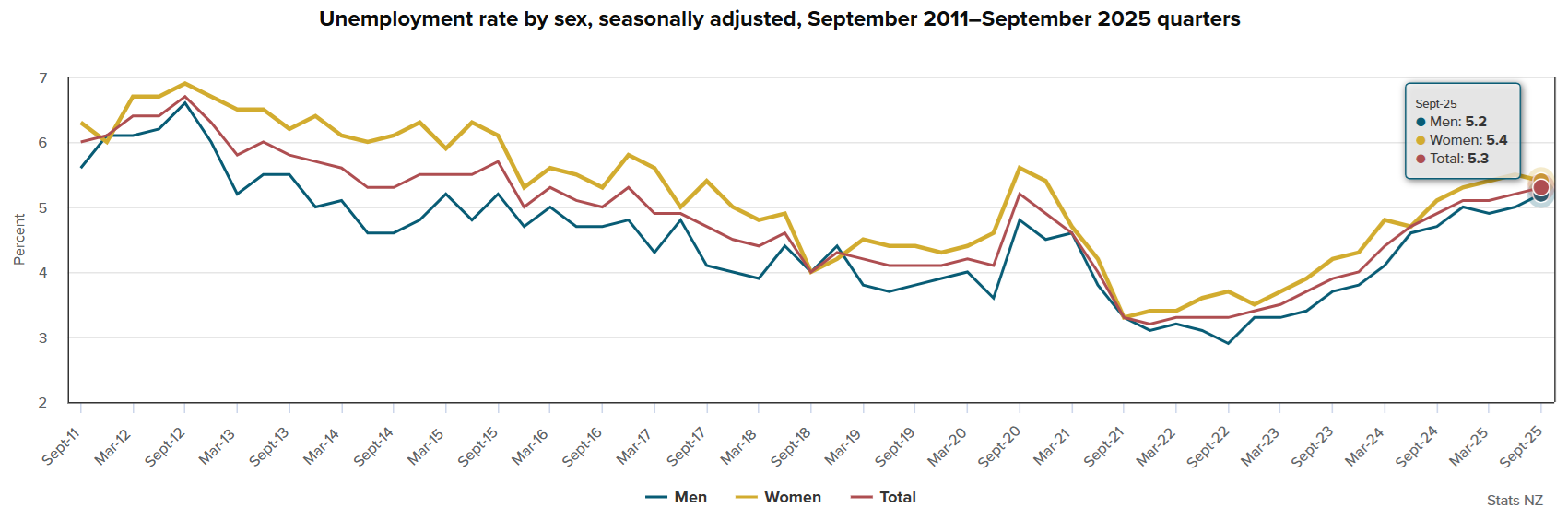

•Unemployment stood at 5.1% in the December 2024 quarter and stayed there in March 2025, before rising again to 5.2% in June and 5.3% in the September quarter.

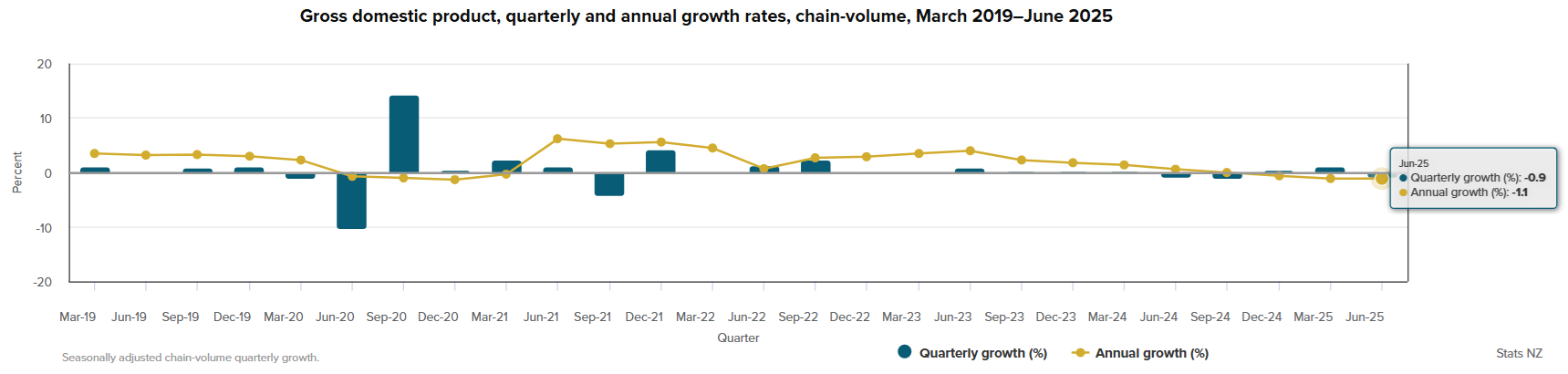

•Our economy, as measured by GDP, grew 0.4% in the December 2024 quarter, then 0.9% in the March 2025 quarter and then jumped off the cliff again with a 0.9% fall in the June quarter. We must wait till December 18 to see what happened in the September quarter.

For those who prefer to absorb their data visually, here's the same three things in graph form:

Well, what do we make of all that? Inflation was a disappointment given what we've gone through to get it down back well within the 1% to 3% target range, only to see it almost back out of the top again. And for all that the talk is that this will be short run, well, let's see. If our currency stays as weak as it is at the moment the anticipated fall back down of inflation to comfortably sit around 2% - which is what's expected - might not be quite such a shoo in.

In its November 2024 Monetary Policy Statement, the RBNZ, was spot on in forecasting unemployment rising to 5.1% in December 2024. But the central bank went early with its pick of the peak, saying that the rate would hit 5.2% in March 2025 (it was still 5.1%) and then falling to 5.0% by September. In the event, it was still going up in September (5.3%), with some hopeful signs that might be the peak - if the economy now starts to pick up.

And, yeah, well, what the hell did happen with the economy? To be honest, I think we have been let down badly with the calculation of our GDP figures this year. I recommend anybody who hasn't seen it to have a read of Westpac senior economist Michael Gordon's dissertation on our GDP figures and his conclusion, (in my layperson's terms) that the aftermath of closure of the Marsden Point oil refinery distorted the calculation of GDP by making it much more 'seasonal' in nature. Gordon estimated that our GDP might have risen 0.2% in the December 2024 quarter (0.4% was the reported figure), then 0.4% in March (0.9% reported) and then a fall of 0.1% (fall of 0.9%) in the June quarter.

These figures sound about 'right' to me based on how New Zealand has 'felt' this year. What such figures would mean is that the apparent strong-ish pick up early in the year didn't really happen and the big mid-year slump was more of a stumble. So, blurrrgh, in other words.

Therefore it's looking more and more to me as if the rises to the OCR in 2021-23, and therefore subsequent increases in mortgage rates, were indeed overcooked. People for the most part coped with the increasing interest rate burden, but even though rates are now in retreat, financial buffers have been eroded and so, crucially, has confidence.

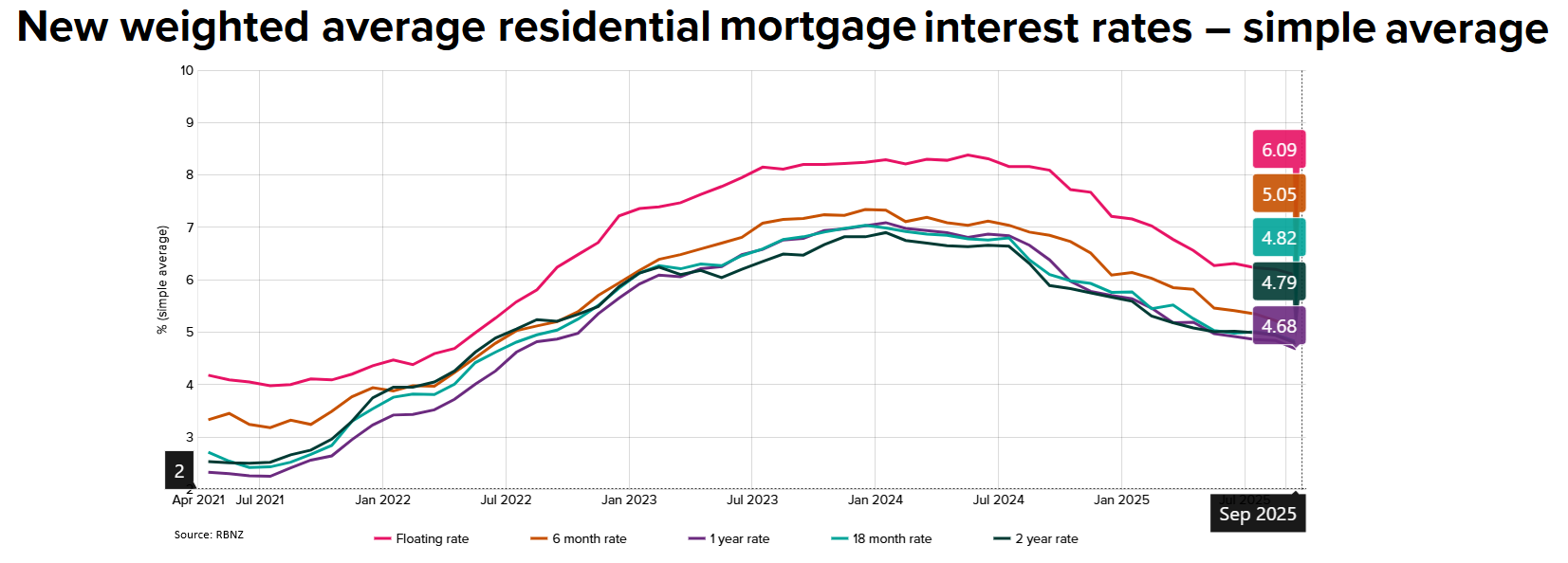

We end 2025 with the OCR at 2.25%, down from the 5.50% peak as of August 2024 and from 4.25% at the start of this calendar year. Now, there are those arguing that the OCR should have been dropped more quickly. But regardless of the size of the cuts, the reductions do take time to feed through into mortgage rates.

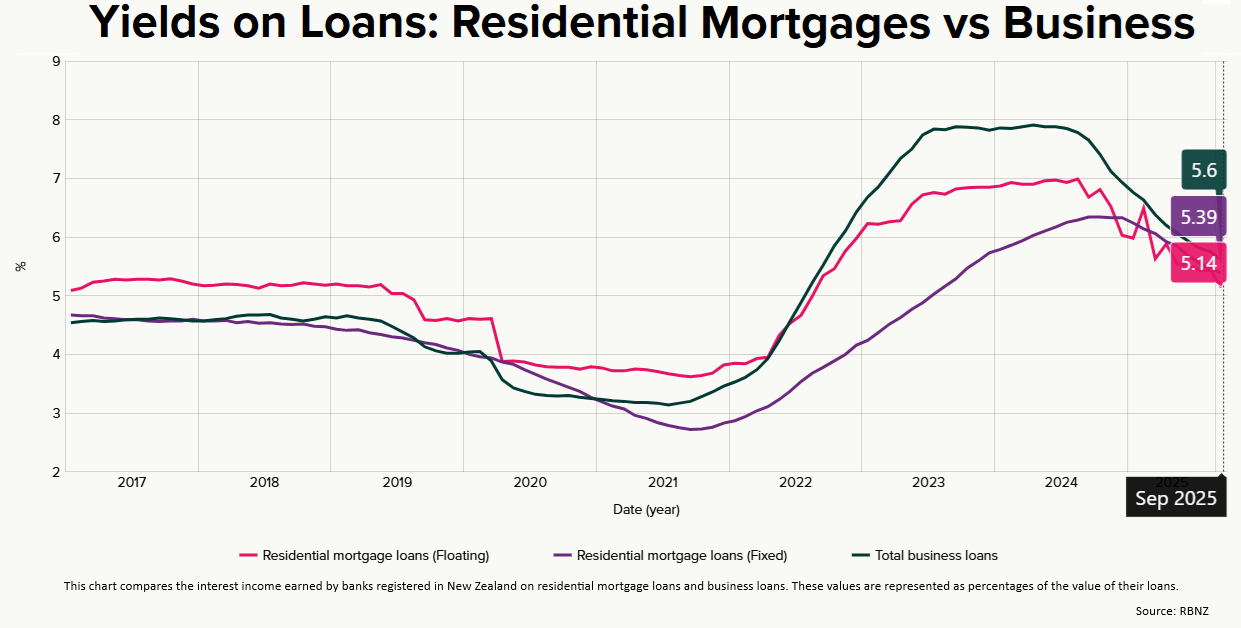

The two graphs below highlight, firstly, the weighted average rates for new mortgages taken up, and secondly the yields the banks are getting from their entire mortgage books.

Across their entire books, the banks were yielding just 2.83% on mortgages (that figure includes both fixed and floating) at the low point of the cycle, which was September 2021. The subsequent rise was substantial and didn't actually peak till October 2024, at 6.39% - AFTER the OCR was already on the way down. As of September 2025 the yield had dropped to 5.36%.

And now, fresh from the horse's mouth and the newly minted November Monetary Policy Statement, the RBNZ says with close to 40% of fixed rate mortgages due to reprice over the December and March quarters, the average mortgage yield is expected to fall further, to 4.7% by September 2026 based on current market pricing.

So, it is gradually dropping, but is still way, way higher than a few years ago.

Regardless of how quickly or otherwise the OCR was cut, people were going to need time to adjust to lower rates. Those who had become accustomed to not spending were going to take time to get comfortable with the idea of spending again. It's not just like turning on a switch.

On top of all this, the uncertainty around tariffs would likely have been a big contributing factor to the stall that was seen in the economy in the June quarter. Businesses hate uncertainty more than anything else. And if they are faced with uncertainty they quickly go into a holding pattern. Which is what I think happened.

And whether we like it or not, we seem as a nation to derive a lot of our confidence - or lack of - from the condition of the housing market.

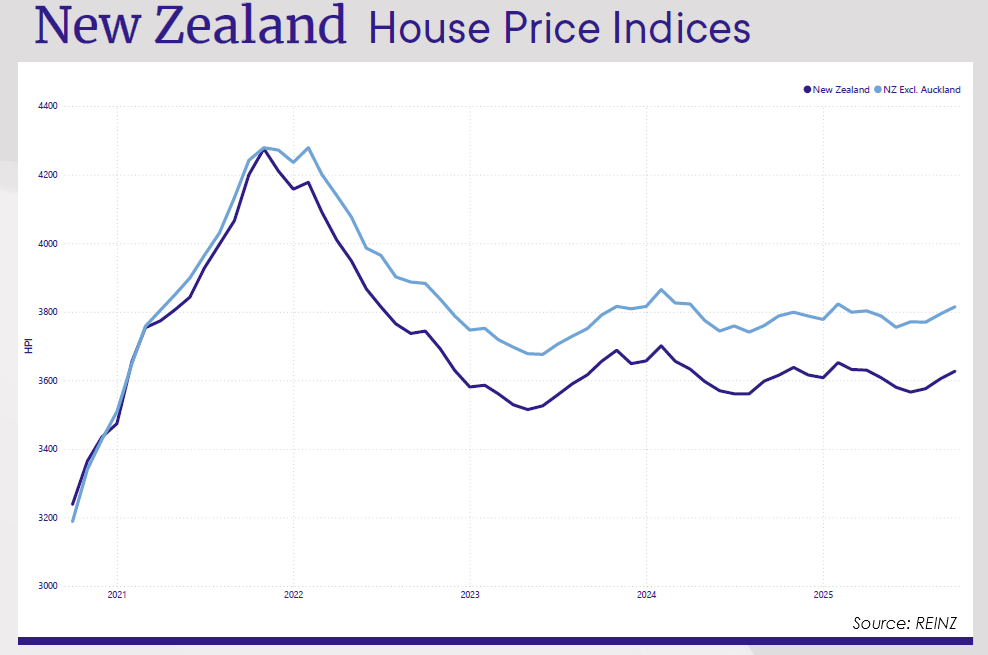

In the run-up to both 2024 and 2025 economists and the RBNZ were predicting pick-ups in house prices that didn't materialise. In its November 2023 Monetary Policy Statement (MPS) the RBNZ forecast that house prices would rise over 5% in calendar year 2024. They dropped over 1%. In the November 2024 MPS the RBNZ forecast an over 7% rise for the 2025 calendar year. That hasn't happened either and it'll be touch and go whether the final outcome for this year is either a very marginal rise or another small fall. I think the smart money is on a marginal rise, but it will literally be something like 1%. In fact the RBNZ's latest cut at it in the November 2025 MPS is for a 0.2% rise in the 2025 calendar year and then 3.8% in 2026.

Why has the market remained flat? Well, by most assessments our market was by no means 'cheap' back in 2019. And then came 2020 and the pandemic and then we had a period in which we added around 40% to prices that weren't cheap in the first place. And then we had big rises in interest rates just at a time when mortgages (due to the price rises) were becoming truly monumental-sized and leaving people fully exposed.

While the non-performing loan ratios have blipped up, it's not been to anything like the degree seen after the Global Financial Crisis. People have managed real well. But managing doesn't mean 'comfortable'. And it could just be that more people than we really know about have ended up in situations either with their own homes or with investment properties that are not ideal for them. And it could be that a lot of people would like to sort out the situation they are in before going forth again with new acquisitions. And remember, it does go against the grain in New Zealand to sell a house for less than we paid for it.

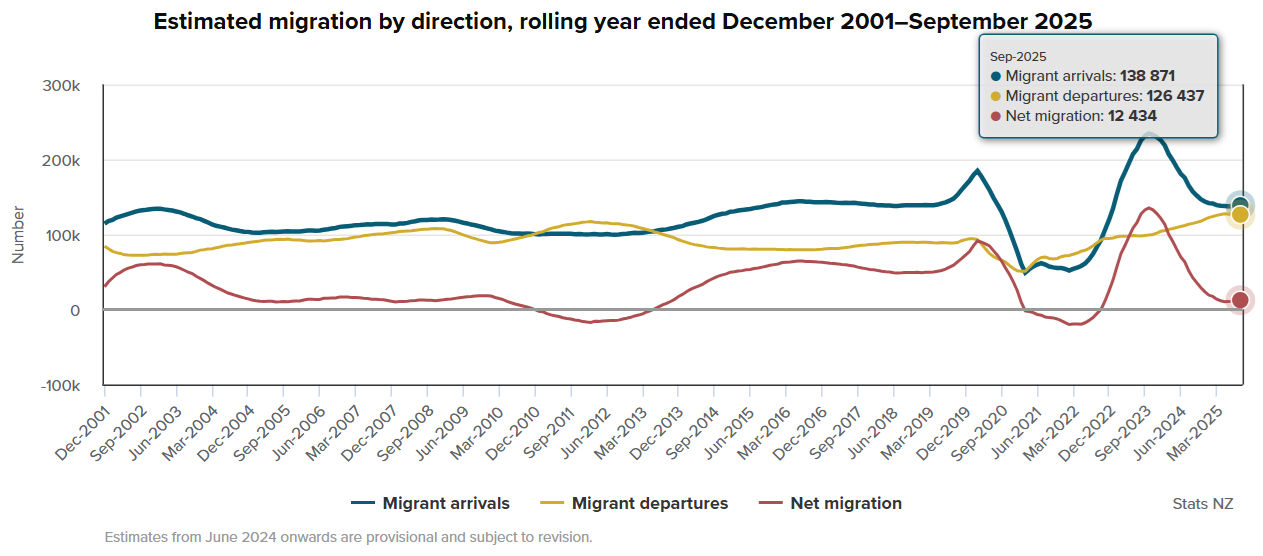

The housing market hasn't been getting the usual sort of support from net migration levels either. Rents have been flat in the past year, which won't have been of great encouragement to investors. In the 12 months to September, the country had a provisional net migration gain of 12,400, down from a 42,400 gain in the 12 months to September 2024 and a 132,700 gain in the year to September 2023.

So, we have a strange stand-still with the housing market at the moment.

And really, that's been a bit how New Zealand has been this year.

I think the clear lesson to draw from it is that our economy takes more time than we might want to think to pick up from the impact of a Reserve Bank-induced recession. We don't just bounce back from a period of high interest rates. And it's worth bearing that in mind for the future. We can certainly have the debate about whether the RBNZ would have been better served by simply dropping the OCR like a brick and getting it down to the levels that it is now early this year. But that would have carried its own risks too.

As for how we end the year, well, there is talk that the economic recovery is finally moving into view. So, will 2026 be better? Well, as usual, I'm not making predictions, as such. But I will, in another article, have a go at pointing out some of the key things to be looking out for. Watch out for that in a few days' time.

*This article was first published in our email for paying subscribers early on Friday morning. See here for more details and how to subscribe.

38 Comments

I think the other thing that may have been holding us back, and that will continue to hold us back next year, is the level of indebtedness, as described in Greg's article yesterday, detailing the high prices being paid by first home buyers, and the high number and percentage of low equity mortgages required to purchase said houses. I think houses prices are still too high relative to incomes, meaning the levels of indebtedness are too high, and that combo is, and will be, a brake on discretionary spending by those with mortgages.

That seems logical to me but many people consider that so long as individually the houses are considered "affordable" then it's all ok. But what may be affordable on an individual level may not be affordable on a national level.

That's an excellent observation - the level of private sector debt in NZ is one of the highest in the world. We may be at the peak of the debt cycle and NZ - at the aggregate - is probably getting close to it's limit. At this point government will need to step in to grow the money supply through fiscal policy.

Not this coalition

Do you mean more money printing, or, just lowering the OCR (underway) so Banks can create more money from nowhere to push to new debtor slaves?

Both options are inflationary and just bail out the stupidly in debt.

As long as there is 'spare capacity' - high unemployment and under-utilization rates - then government deficit spending is unlikely to be inflationary. Deficits are not a liability in the private sector - they are income and savings. Government debt - as bonds - is private sector savings - not bank loans or 'debt'. The liabilities of the government are assets in the private sector - not debt. Government liabilities sit on the opposite side of the ledger to private sector liabilities.

Government debt - as bonds - is private sector savings - not bank loans or 'debt'. The liabilities of the government are assets in the private sector.

Which misses an important question: why does the pvte sector want to to own govt bonds? While they may be attractive to institutions, at the end of the day, they're suboptimal for most people because they "have to" underperform inflation. There is a case for capital preservation and guaranteed principal when deposit rates are near zero.

Tell me how bonds actually help the younger generations? They don't.

I'm not an expert but my understanding is that bonds are used to manage reserves and the private sector money supply. Where reserves are the record of government created money and used for interbank transactions. I believe commercial banks are required to hold reserves and also government bonds.

After bonds are issued by the RBNZ with a specific yield and transferred to commercial banks in the 'primary market'. The commercial banks then sell these to to the private sector on the secondary market. These bonds are considered a safe harbor asset in any savings or investment portfolio - in other words the government is acting as a deposit taker - they aren't 'borrowing' money. From the private sector perspective bonds are a term deposit - not a loan.

The yield on bonds helps set the floor on market interest rates and other return rates which means the OCR flows through the financial sector. Bonds also help to manage inflation by withdrawing money - temporarily - from circulation.

That doesn't answer my question. While govt bonds may offer some value of protection of the preservation of wealth and value of labor, that only really applies to people with substantial assets. It doesn't really apply to younger generations who're screwed by the inflation mechanism. Govt bonds are central to how inflation works, because they sit at the intersection of fiscal policy, monetary policy, and expectations about future prices.

Government debt (or bonds) offer a source of credit creation that does not rely upon short term return. If the only source of credit that was available was private debt then we would face the problem (in aggregate) that NZ is currently experiencing....insufficient return to encourage investment and increasing risk of default as the debt issued increasingly pools in asset values that can no longer provide the needed servicing return.

The government may issue debt (it dosnt have to be bonds but thats the mechanism we use) to enable the return to maintain a level that does not require default (in toto) and maintain a functioning money system.

Unfortunately although this is financially (mathematically) sensible and workable it does not account for real resources and the fact there are multiple monies (currencies) valuing and competing for those disparate and unequally distributed resources.....and then there is force.

Government deficit spending - reduces indebtedness in the private sector because government deficits lower costs and increase demand in the private sector. It's a balance that needs to be maintained between public and private sector debt to ensure the private sector is not overburdened with costs or unserviceable levels of debt.

Do you mean more money printing, or, just lowering the OCR (underway) so Banks can create more money from nowhere to push to new debtor slaves?

Most people struggle with the idea that banks create money from nowhere. They usually default back to the idea of fractional reserve - which doesn't explain it.

Critics accept that banks create money as they lend but argue that describing this as “out of thin air” is misleading, since loans are backed by borrowers’ assets and future income, and banks are constrained by capital, regulation, and risk of insolvency.

Levels of indebtedness are too high

That is 100% the issue. It generally means little to no equity. When the housing bubble deflates the indebted take a hiding so they hunker down smoking hopium that it will all be ok. Banks allow extend and pretend in terms of interest only, payment holiday etc etc. Anything to keep the patient from coding on the table.

Negative leverage is a real thing.

Bank profits are at record levels. They can’t have many repayment holidays and non performing loans.

Its actually mainly because the net interest margin is so high.

Sadly, most of the NZ economic commentariat don't know how the economy works, so we get forecasts based on vibes rather than facts. My forecasts for 2025 were spot on (almost) because I take the flows of money seriously and look at the actual numbers. Fair play to David here for recognising the importance of the effective mortgage rate and its long, long lag. If only RBNZ had done the same in 2023. It was obvious in 2022 that we were heading for recession as credit flows turned sharply negative while RBNZ hiked rates and Govt sought to rein in spending. It was only the burst of immigration in 2023 that slowed the descent.

The 'almost' above relates to my incorrect forecast that we would see house price growth this year. I did not expect the collapse in Labour Force Participation or the exodus of people permitted to buy houses.

I think there's a difference between knowing how the economy works and how we'd like it to work.

For instance, at great effort and much contemplation you attempt to map out how to run it without much if any pain or distruption. But the base assumption is that's what's actually trying to be achieved.

You were not alone in that. Some NZ banks were predicting house price growth of 7% in 2025 and economic growth well above zero. One factor that is completely overlooked is the level of private sector debt in NZ - it is or was recently close to 160% of GDP. Exceptionally high by global standards. So households and businesses may not be able to service higher levels of debt - especially in a stagnant economy with rising unemployment and a deflating housing market.

Then there is the never mentioned fiscal contraction in 2024 which was seen as 'fiscally neutral' because of tax cuts. This completely under estimates the impact of government deficit spending in underpinning private sector demand. The coalition gave the NZ economy a demand shock so fast and hard it still hasn't recovered.

Even if we can afford more debt, we may not want it. I reckon a lot of people have been put off by the RBNZ dramatically yanking the OCR lever back and forward.

We are going to pay our mortgage off ASAP then probably won’t have debt ever again. Will be interesting times ahead for the economy, probably better in the long run.

We've dropped a decent chunk of private debt as a % of gdp, and borrowing is picking up strongly. Expect another little cycle of credit fuelled 'growth' in 26/27.

We've dropped a decent chunk of private debt as a % of gdp, and borrowing is picking up strongly. Expect another little cycle of credit fuelled 'growth' in 26/27.

It's a good punt. By default, we're going to have to follow the lead of the U.S. and everything is pointing to a significant credit-driven expansion starting by Q2 at the latest.

Place your bets accordingly.

"Expect another little cycle of (private) credit fuelled 'growth' in 26/27".....

If enough are convinced (fooled).

Well done. A thorough and detailed article covering many aspects of the NZ economy - except fiscal policy. Whatever you do - if you're a NZ commentator - do not mention fiscal policy.

2026 will be a repeat of 2025 for the same economic reason - contractionary fiscal policy.

I get that fiscal policy influences an economy.

What I don't get, is how people think a really broad tool, like a fiscal policy, will manage to provide the societal improvements that something like socialism fails to do.

Socialism has not failed - our public health system, our universal pensions scheme and free education are all socialist. In a true free market economy all of these things would be paid for by the private sector and would only be provided to those that could afford them.

This is how it was in the 1930's before WW2 but since WW2 nearly all economies are mixed-model - some things we leave to the private sector but other things we don't because the private sector can't deliver non-profitable services whereas the government can.

If it's a mixed model, it's not really socialism then, is it? Socialism more commonly implies state socialism, where you have a planned economy and state controlled production - in order to prevent the issues arising from private industry.

We have a social democracy, with some socialized services. Already underfunded.

Then, we need some more funding, for future infrastructure and other current obligations.

Then we have to find a way where we retain or even improve our financial prospects in light of there being much newer and cheaper industry bases to compete with.

And we also probably should address the issues we face with advanced capitalism, proliferated ownership of most of the core producers of the things we need, that sort of thing. Big players are deemed more efficient and new entrants lack the resources to compete with them.

And fiscal policy somehow can resolve these problems to any considerable degree.

I think we’re at the limit of what the taxpayer is prepared to put into the pot. Once you pay up to 39% tax and 15% GST, half your income is gone. For someone like myself - hardly ever use healthcare, don’t get any benefits, probably won’t get super - it’s already feeling like an absolute ripoff.

It didn't stop many many people from flocking to become engineers, doctors, surgeons, lawyers, and other high paid professions post WWII when the top tax rate was 6%. People still paid their tax and still had more in the pocket at the end of every week compared to others, and with this we build much of the country's core infrastructure. At the heart of it, I see it as everyone wants what their parents had, but those opportunities are no longer available to most due to lack of resources, public funding, quality leadership and most importantly - a united country who are willing to forego something to help each other out.

2026 will be a repeat of 2025 for the same economic reason - contractionary fiscal policy.

Uncertain about this as the current govt have to pull finger to bring tangible results people can see or they'll get voted out as not delivering. This usually required opening the purse strings.

It was the year OCR cuts were supposed to kickstart the economy

There we go yet again,. 2025 is the year the OCR dropped, the improvement in the economy will FOLLOW with a lag of about 18 months. Why don't more people understand this?

Exactly

Labour cannot help themselves...ignoring basic economics.

https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/580428/labour-announces-low-intere…

It’s a good vote winner, even though it probably won’t achieve anything.

Trumps saying he’s going to increase tariffs to replace income tax. So it could be another crazy year ahead.

“Nice country you have here, be a shame if anything happened to it”

https://www.stuff.co.nz/world-news/360903544/trump-says-airlines-should…

In the 12 months to September, the country had a provisional net migration gain of 12,400, down from a 42,400 gain in the 12 months to September 2024 and a 132,700 gain in the year to September 2023.

This is going to be a significant handbrake on economic growth. There's no alternative on the table for this country to grow without major immigration and the associated property boom. The government will begin to panic next year as the growth figures don't come through as expected and their constituents aren't getting their 20% house inflation they've been raised to believe they deserve.

There's no alternative on the table for this country to grow without major immigration and the associated property boom

Those two activities usually occur after we have some economic growth, not before. As in, we attract more migrants after a period of growth, and people also lean into spending more on property after some growth.

I paid a large chunk off my mortgage as I got ready to say farewell to 2.99% in March. Hopefully banks are still competing with each other and I can refinance then and get a nice cashback to call it a cycle. Not long to go now.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.