It has been a long time between drinks for our Top 5 column. A very long time, actually, given the last one was published on July 3 last year!

We haven't forgotten about it and a quiet Friday afternoon has given me impetus to resurrect it. (At least this once!).

And as always, we welcome readers' thoughts in the comments below. If you're interested in contributing a guest Top 5 yourself, let us know; Reach out either to david.chaston@interest.co.nz or me; gareth.vaughan@interest.co.nz.

1) Adapting inflation targeting (IT).

New Zealand, via our Reserve Bank, was an inflation targeting pioneer in 1990. The high inflation that swept the globe in 2022, peaking in NZ with Statistics NZ's Consumers Price Index hitting a 32-year high of 7.3%, has proven a robust challenge to inflation targeting central banks.

A recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) working paper takes a look at how inflation targeting regimes stood up to this challenge in comparison with non-inflation targeting regimes. For some context for this pointy headed analysis, I've included the authors' list of inflation targeting (IT) and non-inflation targeting countries below.

The paper, Navigating the 2022 Inflation Surge: A Comparative Analysis of IT and Non-IT Central Banks, was authored by Patrick A. Imam and Tigran Poghosyan.

In their conclusion they say;

This paper examines how IT central banks performed during the global supply shock compared to non-IT peers. The results are mixed. Inflation outcomes were not consistently better in IT countries, and long-term inflation expectations remained broadly anchored across both groups, particularly at longer horizons. The disinflation that began in 2023 came with similar output costs across regimes. While IT central banks, on average, tightened monetary policy more swiftly and decisively, these efforts did not achieve clearly superior results.

Notably, several non-IT central banks have managed to bring inflation under control quickly, despite lacking a formal inflation target. This raises the question of whether credibility depends on the existence of a formal IT framework, or simply on the presence of a credible nominal anchor, regardless of its specific form. Similarly, central bank independence, while critical, also did not consistently predict better outcomes. This underscores the complexity of the tradeoff between credibility and responsiveness.

That's not exactly a ringing endorsement of inflation targeting. However, Imam and Poghosyan aren't advocating throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

They say the global inflation surge of 2022 was a shock primarily driven by big adverse supply side disruptions following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. The resilience of inflation targeting regimes in the face of such supply shocks was relatively untested, given the previous comparable episode, the 1970s oil price shocks, predated the widespread adoption of inflation targeting as we know it today.

Imam and Poghosyan say;

Overall, central banks today operate in a more complex and uncertain environment than during the earlier decades of IT. While the IT framework continues to offer important benefits, its application may need to adapt to the growing challenges posed by more frequent, global, and persistent supply-side shocks.

And;

Credibility in the next era will require contingent strategies that are robust to regime switches, persistent supply disturbances, and unanchored expectations.

They raise three questions for future research;

▪ What anchors inflation expectations when there is no formal target? Understanding how expectations are formed during supply-driven inflation episodes, and the role of central bank communication, as well as credibility, is essential.

▪ How should monetary policy respond to inflation driven by supply shocks rather than demand excess? The 2022 experience suggests that front-loaded tightening does not guarantee improved inflation outcomes, raising questions about the appropriate pace and scale of response.

▪ What frameworks are best suited for a world shaped by persistent supply shocks? Shocks related to climate change, geopolitical fragmentation, and trade realignments may require a more adaptive and robust approach to monetary policy.

The IMF notes the views expressed in its working papers are those of the authors and don't necessarily represent the views of the IMF.

2) Why the Trump administration is obsessed with Venezuela.

Venezuela may not make the news in New Zealand very often. However, it is doing so at the moment. That's because there's a decent chunk of the US Navy parked up nearby, with US forces seizing an oil tanker off the Venezuelan coast this week. This is, of course, on the heels of US strikes targeting "narco-terrorists" allegedly transporting drugs from the region.

In an article published by The Conversation, Juan Zahir Naranjo Cáceres and Shannon Brincat explain why the US is so interested in Venezuela. Yes, there's the drugs and the obvious economic reason; Venezuela has the world's largest proven oil reserves. But is there more to it than that?

The Trump administration's new National Security Strategy harks back to the Monroe Doctrine named after former US President James Monroe, which saw numerous US interventions in Latin America over decades. In 2013 then-Secretary of State John Kerry may have announced an end to the Monroe Doctrine era, but it's now very much back on.

In typical hubristic fashion, the document openly announces a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, elevating the Western Hemisphere as the top US international priority. The days when the Middle East dominated American foreign policy are “thankfully over”, it says.

The document also ties US security and prosperity directly to maintaining US preeminence in Latin America. For example, it aims to deny China and other powers access to key strategic assets in the region, such as military installations, ports, critical minerals and cyber communications networks.

Crucially, it fuses the Trump administration’s harsh rhetoric on “narco-terrorists” with the US-China great power competition.

It frames a more robust US military presence and diplomatic pressure as necessary to confront Latin American drug cartels and protect sea lanes, ports and critical infrastructure from Chinese influence.

Sanctioned by the US, Venezuela has signed energy and mining deals with China, Iran and Russia.

For Beijing, in particular, Venezuela is both an energy source and a foothold in the hemisphere.

The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy makes clear this is unacceptable to the United States. Although Venezuela is not named anywhere in the document, the strategy alludes to the fact China has made inroads with like-minded leaders in the region:

Some foreign influence will be hard to reverse, given the political alignments between certain Latin American governments and certain foreign actors.

The regime of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro is corrupt, repressive and authoritarian. Meanwhile, the US has seemingly thrown its lot in with Venezuelan opposition leader, María Corina Machado, winner of the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize coveted by Trump. This past week she appeared in Oslo having escaped Venezuela, where she has been in hiding, with US help. So what does Machado offer the US? She;

is pitching a post‑Maduro future to US investors, describing a “US$1.7 trillion opportunity” to privatise Venezuela’s oil, gas and infrastructure.

For US and European corporations, the message is clear: regime change could unlock vast wealth.

3) Every previous bubble rolled into one.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been a hot topic this year. Whether it has been stratospheric share market valuations for AI related companies, or AI's influence in our daily lives, it has been hard to avoid.

Concerns and debate about an AI bubble have mounted. In a recent episode of Bloomberg's Odd Lots podcast, guest Paul Kedrosky of US venture capital firm SK Ventures, nails his colours to the mast. He describes the AI bubble, dramatically, as being like every previous bubble rolled into one. There's a real estate aspect through energy and water sucking data centres, obviously a technology aspect, exotic financing structures, and geopolitical competition raising talk of potential government bailouts.

So the reason why it's going to be historically important is because, for the first time, we combine all the major ingredients of every historical bubble in a single bubble. We have a metabubble no pun intended for Meta. We have real estate. You guys just talked about this, right, Some of the largest bubbles in US history had some relationship to real estate. We have a great technology story. Almost all the large modern bubbles has something to do with technology.

We have loose credit. Most of the major bubbles in some sense have a loose credit aspect. And one of the other exacerbating pieces that some of the largest bubbles, thinking about even the financial crisis, is some kind of notional government backstop. You know, think about the role in terms of broadening home ownership in the context of the real estate bubble, and the role that Fanny and Freddie played and loosening credit standards and all of those things. This is the first bubble that has all of that. It's like, we said, you know what would be great, let's create a bubble that takes everything that ever worked and put it all in one. And this is what we've done.

It's an interesting, albeit alarming, listen.

4) APRA and the Aussie housing bubble.

Speaking of bubbles, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority's recent announcement about limiting high debt-to-income (DTI) home lending "to pre-emptively contain a build-up of housing-related vulnerabilities in the financial system," caught the eye.

Ian Verrender, the ABC's chief business correspondent, weighed in with an explanation for APRA's attempt to take the hottest air out of Aussie housing. He describes it as a bubble;

that's been taking in oxygen for almost three decades, ever since our banks decided entrepreneurs were way too risky.

Given Australia and New Zealand's close economic relationship, and the parents of our big four banks being Australian, APRA's efforts are certainly of interest.

Affordable housing. It's a topic almost as popular as bubble mania.

But for all the talk, Australian housing seems to be on a never-ending trajectory of price gains. Affordability has never been worse and it's unlikely to change.

It's the very definition of a bubble, fuelled by overly generous tax concessions, huge population growth and a banking system that has engaged in a symbiotic relationship with real estate.

Higher prices require more debt. Bigger loans deliver bigger bank profits. Even during the most torrid round of interest rate hikes in history just two years ago, housing prices, after an initial fall, barely skipped a beat.

Governments invariably make the situation worse by throwing money at first home buyers, which only ever benefits first home sellers as prices rise.

For a country with a tiny population and an abundance of land, Australian real estate is amongst the world's most expensive, now valued at more than $11.6 trillion.

Underpinning it is debt at close to $2.6 trillion. It represents far and away the biggest component of our four big banks' combined lending portfolios, in turn creating a potential threat to our banking system if it were to suddenly unravel.

And that explains the sudden interest from our monetary regulators, APRA and the Reserve Bank of Australia.

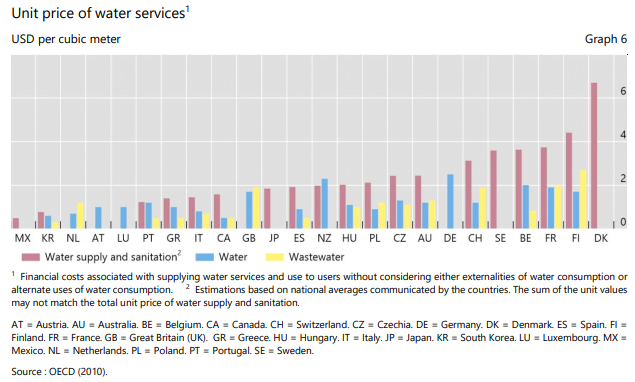

5) Water and the obvious economics.

In something of a no s**t Sherlock moment, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) appears to have discovered the importance of water, and water's economic importance. This may be a bit of an unfair assessment, however a working paper from the central banks' bank, The economics of water scarcity, does somewhat point out the obvious.

The abstract of the paper, by Jon Frost, Carlos Madeira and Serafín Martínez Jaramillo, says;

In many countries around the world, water scarcity could become a macroeconomically relevant concern. As a key input into production processes (agriculture, power generation and industrial use) and a common good, water resources risk being overexploited. Regressions with panel data for 169 countries between 1990 and 2020 show that, while water use is positively correlated with output, higher water scarcity is associated with lower gross domestic product growth and investment, and higher inflation. In contrast, water use efficiency is associated with higher gross domestic product growth and lower inflation. Climate scenarios show risks of much more severe water shortages in the future, threatening its sustainable use. This could impose higher costs on individual sectors and on the economy, reducing output and pushing up prices. Water availability and use could thus become an area for economists and central banks to monitor in the context of climate change, economic forecasting and monetary policy.

I would've thought water scarcity was already "a macroeconomically relevant concern" in numerous parts of the world, including in parts of New Zealand. However, I guess it doesn't hurt to have boffins notice this, and publish it under the auspices of the BIS. (They do acknowledge "current and future" water scarcity later in the paper).

As with IMF working papers, BIS ones are said to express the views of the authors and don't necessarily reflect the views of the BIS or its member central banks which include our own Reserve Bank.

9 Comments

My understanding of the Aussie housing bubble is that the family home doesn’t count towards superannuation asset testing. So it makes sense to invest every cent you own in your house. If we get something similar in NZ then I certainly would do that too.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been a hot topic this year. Whether it has been stratospheric share market valuations for AI related companies, or AI's influence in our daily lives, it has been hard to avoid

Some heat has already come out of the speculative shares. IREN down 30% in a month and 50% off ATH in Nov. Could be just the start of the reckoning.

Michael Burry (of the former Scion Investments, who made around 800 million USD from correctly assessing the US property market risks in 2008) made extensive investments in water-related entities and instruments for some years. I wonder which way he was betting?

Oh. And he's also been warning about the risks of AI: not reassuring.

Although the US is listed here as not having an inflation target, in fact the FED has been explicit since 2012 that the target is 2% per annum. Before that, the FED also had a target of 2% but it was not explicit. One difference between NZ and the US is that in NZ the target and range is set by the Government whereas in the US it appears to be set by consensus among the Board members. So things could change once the Board gets a new chief next year.

Those countries that do not have an explicit target are nearly all developing countries. The exceptions are China and Switzerland, but those two countries stand out for consistently achieving very low inflation. This very low inflation in Switzerland and China does not occur by chance.

Switzerland probably has low inflation as it couldn’t possibly be any more expensive

Keith, FYI, this is the authors' explanation regarding the US;

In some cases, classification is not clear-cut between the AREAER and the actual policy framework. The United States is not classified as an IT country, but the Federal Reserve was operating under a flexible inflation-targeting framework until August 2020, when it adopted flexible average inflation targeting. Therefore, we include the U.S. in the IT group as a robustness check. The Swiss National Bank does not describe its framework as formal inflation targeting, but its medium-term definition of price stability (0–2 percent inflation) and reliance on conditional forecasts align closely with IT practices; it is therefore tested as part of the IT group for robustness check purposes. By contrast, while some view the Monetary Authority of Singapore as an inflation-targeting central bank, its framework is centered on managing the exchange rate, and it is therefore classified as part of the non-IT group and tested as part of the IT group for robustness check purposes.

The IT regimes were taken from the AREAER report of the IMF, 2023 vintage. It is important to mention that the AREAER definition is based on the de jure classification of monetary policy regimes.

Thanks Gareth

In my opinion, one way or another nearly all countries target inflation using interest rates. But some countries do it more successfully than others. Also in my opinion, the RBNZ in the last five years has become one of the less successful executors of this interest rate policy, being too late to see the turning points and using too much brake and accelerator. Investors and home buyers cannot afford to respond when the cycles are short and sharp.

Investors and home buyers cannot afford to respond when the cycles are short and sharp.

We could Keith, if we had a competitive floating rate as Australia does, however we are at the behest of their banks to give us the grace to do so, which will never happen as they are there to make profit, not for the goodwill of the people. I find it astonishing personally that we use interest rates to change spending behaviour, knowing full well the delay in the effect of this, and that the delay in behavioural change is due to the big banks who, in turn, create money and profit from the extensive data they have on spending and saving behaviour. Gives me the idea that the RBNZ can posture how they wish, but the banks are more in the drivers seat.

With the advent of cheap solar power, the last chokepoint that has frustrated global desalination efforts is finally loosening. The cost of the energy used by desalination plants over time dwarfs the initial cost of their construction, so the availability of cheap solar power greatly increases their viability. The ease with which countries can store water also means that solar power’s chief drawback, intermittency, may be much less of a problem here than in other uses.

...One way to reduce the costs involved in reverse osmosis would be to make the process more efficient by only treating seawater to the point that it can be mixed with the water the nation already has access to. Water produced by reverse osmosis is typically much purer than is needed, and is often intentionally remineralized. Allowing a certain amount of dilution with groundwater, for example, would be less costly while still producing water that is safe to drink.

https://worksinprogress.co/issue/rivers-are-now-battlefields/

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.