Last week I discussed the Green Party’s wealth tax proposals, and commented about how what makes New Zealand an outlier in world tax terms is not so much that we don't have a capital gains tax, but we also don't have an estate tax, gift tax, land taxes (other than rates), stamp duties and taxes on wealth or wealth transfers, which exist in many other jurisdictions.

This prompted reader kiwikidsnz to respond as follows

It's a really interesting comment and thank you for that, because it gets to the heart of the issue around tax and how it changes people's behaviour. Tax is regarded in economic literature as a deadweight cost. Any tax is therefore distortionary, but we have taxes because they pay for things that people like, such as roads, schools, hospitals, infrastructure and pensions, and a whole heap of other services. Accordingly, a key purpose of taxation is to raise the maximum amount of revenue without producing too many distortions and disincentives.

International Monetary Fund on productivity “a significant challenge”

kiwikidsnz’s comments coincided with a report issued by the International Monetary Fund (the IMF) on New Zealand's productivity challenge. This paper was prepared following the IMF’s visit here in late February and early March as part of their annual review of the New Zealand economy and it does not make for good reading.

As the paper’s opening paragraph notes:

“Weak productivity growth poses a significant challenge for New Zealand's long-term prospects. Low productivity growth partly reflects structural factors, including New Zealand's remote geography and small markets, as well as the relatively large role of the tourism and agricultural sectors. However, it also reflects costs and incentives for investment and innovation, which are in turn shaped by features of the business environment and limited financing options.”

Tax is a part of the business environment and as mentioned above the question arises about the distortionary effect of tax. Now the report, and I recommend reading it, is relatively short, but it's very thorough. But as I said, it's pretty grim reading because

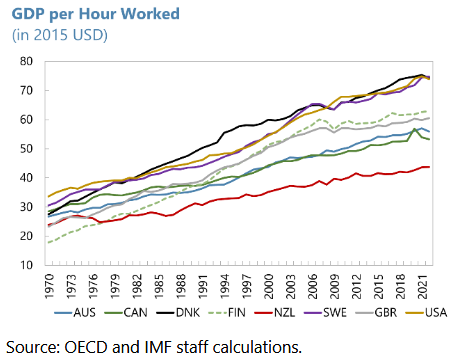

“Over the past five decades, labor productivity growth in New Zealand has lagged that in peer advanced economies, resulting in a widening gap between New Zealand’s GDP per hour worked and that in peers. As a result, by 2022, GDP per hour worked was well below levels in comparable economies.”

A productivity growth challenge across the economy

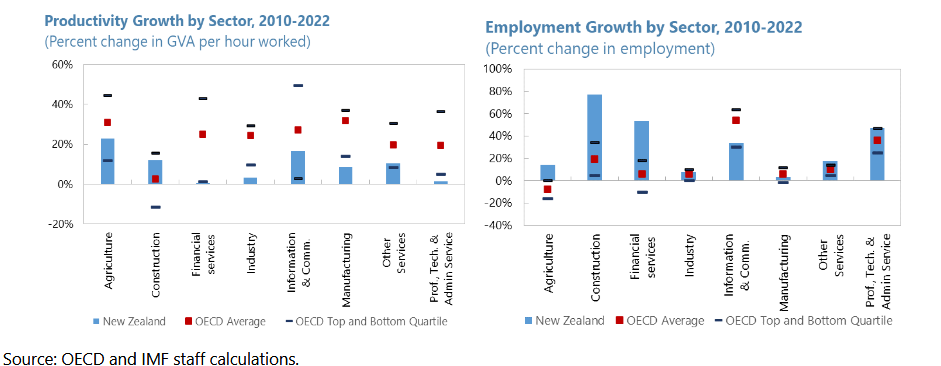

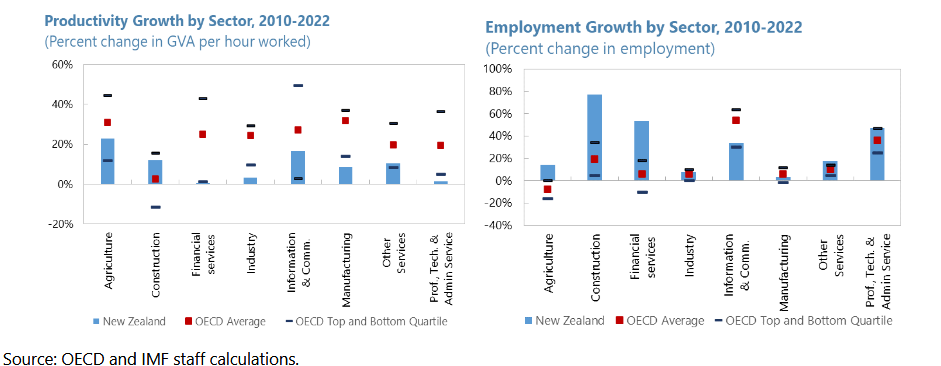

The paper examines this why this has happened and it's not good reading. A part of the paper that really jumped out at me was paragraph 8 Productivity at the Sector Level. According to the paper labour productivity growth from 2010 to 2022 was below the OECD peer average in agriculture, information and communication (ICT) and some service sectors. In fact

“Productivity growth in New Zealand was in the bottom quartile among OECD peers for financial services, industry, manufacturing and professional and technical service sectors over the same period. The only sector where productivity growth in New Zealand was above the OECD average over this period was the construction sector. New Zealand's productivity growth challenge thus does not appear to be confined to a few sectors, but to reflect broader issues across the economy.”

Basically, it appears our high immigration has been masking the low GDP per capita growth. ”New Zealand’s workforce has not witnessed the same efficiency gains as workforces in AE [advanced economy] peers (has not been ‘working smarter’), but it has compensated for this with adding more workers at a faster pace.”

Not enough gazelles and too many in the wrong sectors

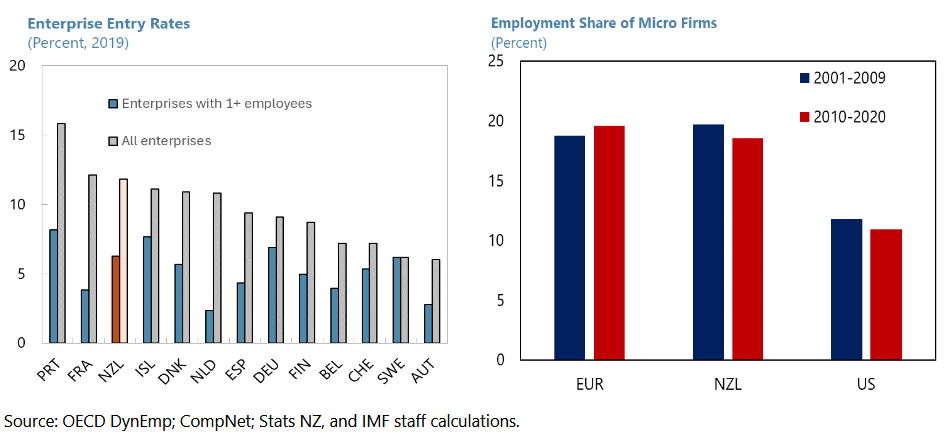

Another damning part of the report is Section B In Search of New Zealand’s Gazelles. Gazelles are young high growth firms that see 20% growth in sales over at least one three-year period when they are under 10 years, from a base of at least USD100,000. Basically, we don’t have enough:

“Since the Global Financial Crisis, birth rates of gazelles in New Zealand, as a share of all new firms established, have been below the median observed in peer advanced economies. At around 13% gazelle birth rates in New Zealand were below levels observed in Australia, Finland or Sweden, but above levels observed in the Netherlands or Denmark.”

Paragraph 14 of the report I think, gets to where the real problems within our economy have arisen, and where tax may have played a very significant part. It notes young, high growth firms in New Zealand have been concentrated in a few sectors:

“Over 2008 to 2018 new gazelles in New Zealand were primarily concentrated in the financial and real estate sectors. The share of new gazelles in this sector was higher in New Zealand than in most peers, even as the sector saw lower overall productivity growth. At that same time, the share of new gazelles in ICT and professional and technical services, which include hi-tech product, high-productivity sectors dependent on innovation, has been lower in New Zealand than in peers. These trends suggest investment and innovation incentives may be misaligned between sectors in New Zealand. Trends could also be a symptom of the high propensity to save in real estate.”

This is where I think the issue of our lack of capital gains tax and a general lack of capital taxation comes home to roost. The incentives to invest in businesses have been trumped by the investment and lending practises in real estate. I think it was a particularly telling comment here about how those new gazelles, which are a very important part of productivity growth, are primarily concentrated in the financial and real estate sectors.

Replacing one set of disincentives with another

To pick up the issue that kiwikidsnz raised, economic efficiencies do arise from tax policies. Removing incentives such as 66% tax rates and a whole pile of distortionary tax incentives that are given because a government is trying to promote particular behaviour is a good move. But there's also the disincentives to divert capital if you do not tax something, and it’s is becoming clearer and clearer to me that this is the biggest single problem with not taxing capital gains comprehensively. Coupled with bank lending practices what has happened is we've diverted resources into real estate resulting in lower productivity growth and less efficient use of our limited capital. That's a policy issue that all parties need to consider.

The Australian counter-example

It's worth talking about the long run implications of the Rogernomics reforms that happened starting in 1984. In October 1985 Australia was also going through its reform period but taking a more measured approach. One of the things it did was to introduce a comprehensive capital gains tax with effect from October 1985. We actually therefore have 40 years of examples to look at what happened around productivity.

Now productivity growth in Western advanced economies has been an issue, but Australia has seen higher productivity over the past 40 years. It has a capital gains tax. We have had lower capital productivity growth, and we don't have a capital gains tax. Now, correlation is not causation, but there's 40 years of examples there to make everyone think very hard that maybe in this case correlation does equal causation.

Interestingly, around the whole question of the 1980s idea of supply side economics and cutting taxes to generate economic growth, generally now seems to have run its course, and it probably was always going to do that. Simply because if you're starting in the 1980s, individual tax rates were then at 60-70% and even more, in some cases. If you're cutting rates down to 30-40% that’s a significant move and you're bound to see something happen. But once rates get down to 30%-40%, the impact of tax cuts is less clear.

Meanwhile, in America, maybe not such a Big Beautiful Bill?

What's really interesting is at the same time as the IMF report came out over the United States) someone who's been described as the MAGA movement's top economic guru, Oren Cass, has come out and been very critical of the latest President Trump backed tax cuts included in the Big Beautiful Bill (yes, it really is called that). Mr. Cass is the chief economist for the right leaning American think tank American Compass. He remains the leading proponent of conservative economic populism amongst allies of President Trump.

In talking about the Big Beautiful Bill and the tax cuts that have been included in that, Oren Cass has basically said that the ideas around the Laffer Curve and supply-side theories which have dominated tax policy thinking for the last 40 years have essentially run their race. After commenting “There's much less confidence in the 1980s-style supply-side tax cutting” he went on

“The reality is we are not going to solve our economic problems if we do not get serious about the fiscal push and fiscal picture and actively reduce the deficit that's going to require both reduced spending and raising revenue. If you're not willing to do that, then I don't think you can credibly say you're addressing our economic problems.

…Whereas in the past you would have just said, “Well, this thing pays for itself,” This time there is a recognition that it does not pay for itself, — and we have a fiscal crisis — so we also need to explain how we’re at least partly going to pay for it.”

This is an absolutely astonishing admission to hear from a right wing think tank, and particularly in America, which is the home of the supply-side theory.

The thing to keep in mind about taxes, as I said last week, it's all about politics. But taxes reflect economies and economies change. kiwikidsnz was right to make the comments that there were inefficiencies in our tax system in the 1980s and they were ripe for reform. But it is not a question of set and forget and that's it, job done, we never have to change again. The dynamics of tax and economies change all the time. And our thinking around that needs to change and reflect that. As a few people pointed out in response to kiwikidsnz we may not have a capital gains tax but other countries do and they have also inheritance taxes, stamp duties, etc and in most cases those peers are wealthier than us. There is 40 years of evidence to suggest that non taxation of capital isn't actually the economic Nirvana you might think, and it has distorted our economy, particularly our productivity as the IMF notes.

Dr Rod Carr on markets: “myopic, reckless and selfish”

On a related point there was a really interesting leader opinion piece by Dr Rod Carr in the Sunday Star-Times on 1st June. Dr Carr has had a hugely impressive career. He's been previously chair of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, worked at Treasury in the 1980s during the Rogernomics reforms and was the inaugural chair of the Climate Change Commission. In summary he has a vast wealth of knowledge about economic policy development in New Zealand over the past 40 years.

His topic was the role and influence of markets. Looking back, after completing an MBA in Columbia University in the mid-1980s, there was little doubt then that markets could allocate financial capital more efficiently than politicians and technocrats and corporate conglomerates. And he believes markets are still, “ruthlessly efficient at allocating privately scarce resources with a price.”

However, he continues markets are “myopic, reckless and selfish,” and understate future benefits and exclude or understate future costs. This results in

“…underinvestment in long-life infrastructure, the degradation of natural ecosystems and under investment in public health and education markets. Markets are reckless because we have created an asymmetry that sees profit accrue to those with private property, while costs are left to lie with the general public.”

He concluded “Markets should be a tool to enable us, not a mantra to enslave us.”

After 40 years, time to think again?

If you combine what Dr Carr said with the comments of Oren Cass and the IMF report on productivity, we’ve now had 40 years of results to look back at how our tax system has evolved and worked in relation to taxation and capital. In my view the long and the short of it is, it hasn't gone according to plan. Maybe it's time to look at the script all over again and rethink how we want to have our capital used if we want to start growing a few more gazelles, lift productivity and our living standards.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā.

8 Comments

It's quite encouraging to see that Terry reads the comments...

However I will point out that my comment did not refer to CGTs and I am on the record in this forum years ago supporting their introduction for realised gains in investment property & business sales (on the increase in the goodwill component of a business). Not including family homes.

Business pay tax every profit step of the way unlike housing investors and employ most people working in NZ. Why should they get a CGT as well...?

Simple. A land tax. Target lazy tax free speculation in land with offset reduction in income tax. With a side order of lower house prices and people motivated to work a lot of issues are solved.

Speculators will take a hit as will Bank profit. There's the problem...

I wonder if anyone has quantified the degree of land-banking (i.e., idle land that could be put to better use). LVT proposals all tend to want to avoid taxing the land under the family home. Given we've just come off a bit of a building boom of new subdivisions and row townhouses, I just wonder how much a land tax (should it exclude the family home and working farms/agricultural land) would bring in.

Also very interesting the recent census stats on 65+ income/wealth;

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/thousands-of-over-65s-earn-more-than-2000…

No matter what we do on tax - It seems to me we do need to modernise/design for current conditions as Terry suggests.

I'd agree with everything noted, but wonder whether, over the 40 year period referred to, haven't we missed the boat with CGT (on residential RE, that is). I assume (perhaps wrongly), that the gains are calculated from the time the new tax is introduced. Can't see that being of much use for at least the next 10 years or so.

Which is why I find inheritance taxes more equitable as they more appropriately capture that part of the boat that has sailed.

Agree the boat has missed bus. That's why Land tax is so good. It's simple, unavoidable, and forces productive use of land. Let's face it pretty much every rental fails a return on capital test. Only really works after the rest of society is screwed by a decade of inflation.

And what exemptions would you propose to a land tax?

Combine the low productivity side of things with the significant social issues our love of housing has created (child poverty, health issues, homelessness etc etc) and it is clear to me we need to change.

But the flipside to this is that a whole generation has been told "work hard, buy a house, pay off the mortgage" so it will take bipartisan support to change anything. And good luck with telling a politician not to be selfish...

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.