By Chris Trotter*

Those who enter politics for idealistic reasons are generally disappointed. With a dispiriting consistency the ordinary voter remains stubbornly indifferent to great causes and grand schemes. The key democratic motivator: the maker and breaker of left- and right-wing governments alike; is whether the politicians have made it easier, or harder, for the ordinary voter to get by.

If the research of the American psychologist Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) is to be believed, humanity’s interest in great causes and grand schemes becomes politically decisive only after its individual members enter the upper stages of his famous “hierarchy of needs”. Employ these individuals, pay them well, give them a house to live in, keep the prices of basic household items and services affordable, and ensure the ready availability of quality health and education services. Only then: only when these basic material needs have been satisfied should politicians start pitching big ideas to the electorate. Who knows, with the basics taken care of, the ordinary voter might even be ready to listen.

Clearly, just moving most citizens off the two lowest of Maslow’s five levels would be an extraordinary accomplishment for any political movement. By the time most of us feel confident that friendship, family and sexual intimacy are set to remain permanent aspects of our lives, then a fairly large chunk of any government’s work should probably be considered done.

If a large number of citizens remain trapped on Levels 1 and 2, however, no government should feel secure. When basic physical needs – food, shelter – are not met. Where personal safety and a sense of belonging are lacking. These are the circumstances in which democratic governments struggle to retain office.

The National-Act-NZ First Coalition Government seems to be aware of this need to respond to the electorate’s basic needs, but adamantly opposed to adopting any of the measures most likely to meet them. Over the last 40 years huge ideological roadblocks have been erected in the path of measures which have, historically, proved remarkably effective at lowering the cost of living. Neoliberal economics, the reigning paradigm in both Labour and National since the mid-1980s, has anathematised direct government intervention for the purposes of keeping prices in check.

Let’s begin with basic food items: milk, butter, cheese, bread, meat, and vegetables. The prices of these staples have soared over the past twelve months. Bringing those prices down by government decree would, of course, play havoc with the profitability of New Zealand’s agricultural producers. Why should a farmer make food available to domestic consumers for less than he could receive from foreign buyers? On the other hand, why shouldn’t the state purchase enough foodstuffs to satisfy the domestic market at the international price, and then make it available to consumers at a price they can afford? Why not subsidise food?

Subsidies played an important economic role in the immediate post-war period in many countries – New Zealand included. The exigencies of wartime had elevated the basic needs of the working population to a point where it seemed both ethically and politically risky to downgrade either of them. Nation states wore the losses incurred by subsidisation because the notion of placing the profitability of private actors ahead of the public’s ability to feed itself at a reasonable price was dismissed as unacceptably extreme. The passage of 30 years was required before the doctrine of putting profits before people could be presented as reasonable.

Of course the New Zealand economy of 2025 still features a significant amount of subsidisation. Employers are excused from paying their workers a wage commensurate with their basic needs by the state support made available to employees via the Working For Families scheme. Landlords are similarly subsidised by the Accommodation Supplement – a state provided top-up payment for tenants unable to pay their rent on account of either inadequate wages or meagre social welfare benefits.

The alternative to subsidisation – prior to the triumph of “market forces” – was direct price control. Indeed, when the free-market revolution got underway in late-1984 New Zealand was still enmeshed in the wages and prices “freeze” imposed upon the entire New Zealand economy by the National Party Prime Minister (and Finance Minister) Rob Muldoon in June 1982.

Conceived as a means of keeping consumer goods affordable, and breaking the wage-price spiral which continuing high inflation made inevitable, the Freeze was at least partially successful. Inflation, running at an eye-watering16.1 percent in 1982, had plummeted to just 6.1 percent in 1984 – an inconvenient truth buried deep beneath the rubble of “Muldoonism” by generations of Neoliberal myth-makers. Four years of monetary mayhem and a stockmarket crash would be required to bring the rate of inflation back to the low point it reached during Muldoon’s last year.

Certainly, Muldoon’s Freeze produced a more tangible result than Labour’s “Maximum Retail Price Scheme” (MRP) of a decade earlier. Introduced in 1974 under the Labour Government of Norman Kirk, the MRP was intended to place a ceiling on retail prices and thus encourage that scourge of the capitalist profit system – competition by price. Resisted ferociously by the serried ranks of the Right (many of whom, Bob Jones in particular, were already scenting the heady possibility of a major electoral reversal courtesy of its then admired attack-dog, Rob Muldoon) and unsupported by the computer technology that would have obviated the massive bureaucracy required to administer it, the MRP was timed-out logistically, politically, and electorally.

In the struggle to contain the cost of basic consumer goods and services there is, however, one sector that offers a long and proud record of success – publicly-owned and provided insurance. In both the life and property aspects of the industry, it soon became clear to New Zealand’s political leaders of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries that affordable insurance could not be provided to ordinary New Zealanders by any other entity but the state. Government Life was established in 1869 and by 1877 was larger than all the other life insurance companies combined.

The State Fire Insurance company opened for business in 1905, and was immediately faced with a coordinated effort on the part of private insurers to drive it from the field. By 1920, however, the state-owned company had, according to Te Ara Encyclopaedia “insured more property than any other general insurance company in New Zealand.”

Naturally, faced with the extraordinary danger of a good example, the Neoliberals of the 1980s and 90s lost little time in privatising these state-owned guarantors of affordability. The names of these now private companies may stir echoes of a less ideologically hidebound age, but the ever-rising premiums currently confronting New Zealanders have yet to convince the leaders of National or Labour that the example set by their more pragmatic predecessors, if followed, might bring substantial electoral rewards.

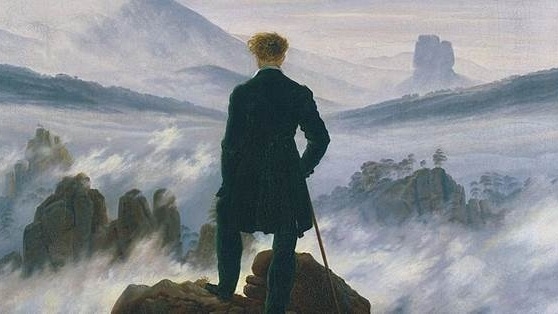

Professor Maslow was puzzled by the unwillingness of practical politicians to do all within their power to lift the mass of their voters up to the top three levels of his hierarchy of needs. There has never been any question that the capitalist system could do it. Indeed for millions around the world the “self-actualisation” for which Maslow encouraged us all to strive is there for the taking – if only they would reach for it.

Could it be that if happiness is available to all, then it’s value, as both a goad and a goal, will be diminished? Perhaps it is only possible for human-beings to enjoy the view from Maslow’s First Level by reminding themselves that there are four, increasingly unhappy levels, below them.

*Chris Trotter has been writing and commenting professionally about New Zealand politics for more than 30 years. He writes a weekly column for interest.co.nz. His work may also be found at http://bowalleyroad.blogspot.com.

34 Comments

While New Zealand's tiny, remote market makes attractive the prospect of state-run organisations to provide important goods, services and activities at a reasonable cost, those of us who were around at the time remember what heavy state control was like.

There was little apparent perception in government that the heavy centralised control of so much activity needed to be tied to an obligation to be humane and to use the public purse as efficiently and effectively as possible, while not making the bureaucracy's development an end in itself: you needed permits for everything and the default answer to change was regulation that usually said "no" to innovation..

You could say the same thing now, but the "over it" public mood then allowed the political room for the slash-and-burn changes of the Labour Government.

How do you create centrally run services without imposing inordinate amounts of sludge and crippling the ability to adapt to new circumstances?

How do you create centrally run services without imposing inordinate amounts of sludge and crippling the ability to adapt to new circumstances?

Isn't there a fair bit of sludge slurping around in Fletcher's today, a product of the neoliberal dogma? What about the rape and pillage of the rail system under privatisation? The lack of maintenance and development of the national grid for a protracted period once NZED was disestablished and transformed into ECNZ.

What about the exorbitant costs of infrastructure developments delivered by private sector contractors? Are they really more efficient in delivery of the end product than the Ministry of Works would have been? Transmission Gully comes to mind here and the traffic management crew that turned up with cones and lollipops on a gravel road that sees 20 vehicle movements on a busy day.

Sludge? All depends on how one defines the term. I reckon in the current environment, we, the common people, are close to neck deep in it while private interests that control so much of our essential infrastructure and services are laughing all the way to there private luxury bolt hole.

Yes, I agree there were inefficiencies in government departments in that highly regulated era. But there was no profit extraction. And the employee pay scales were lower than private sector because a government department job was a job for life. Now government employee remuneration is higher than comparable private sector roles. If indeed there is comparability.

You did read the third paragraph, right?

In a lot of cases we've simply swapped bureaucratic authoritarianism for commercial monopoly. A lot of the time it can be hard to tell the difference.

Subsidising can reduce purchasing-power stratification but cannot address the population vs scarcity predicament.

As this overshot human population continues to draw down the resources of this obviously-finite planet, discretionary 'spend' will continue to give way to essential 'spend'. But all the proxy in the world, doesn't conjure up a potato, or a cow. Nor does it replenish soil nutrient (currently 50% done by Haber Bosch using natural gas - a finite resource). Nor erosion. Not the other resources - particularly fossil oil - which are getting harder and harder to extract from said finite planet.

The physics of all that will continue to worsen. We levered one-off stocks of planetary parts, to overshoot ourselves. We are entering a period of repercussions. And some folk doggedly insist on accounting for our trajectory, in a way which does not account for our trajectory.

We call that accounting system 'money'.

What far too many of our politicians forget or choose to ignore is that when elected into power they represent ALL of the voters, not just those who voted for them. In any democracy it is the swing voters who decide who the government will be, and no party can be certain the majority of those who voted for them are not swing voters. So ignoring the needs of the people of the country, no matter how mean those people are, is done so at the risk of your power and influence. Even the wealthiest are impacted by crime and violence and its causes.

Some would label some of what CT is suggesting here as socialism, but in reality it is more 'democracy'. No government can afford to make unemployment more attractive than employment, and no government should be sitting idly by when those in employment are struggling to provide their own basic needs.

Significant change needs to happen. Who is going to get it done?

"Some would label some of what CT is suggesting here as socialism, but in reality it is more 'democracy'."

No it isn't. Those of us who were working & raising families in the early 1980s know that blighted era's State price, wage & rent setting is well beyond/behind any version of democracy.

Don't be an extremist KKNZ, there are limits to what governments can or should do, and the swing from the Muldoon era, through to Lange's bunch implementing the flaw 'free market' policies was a big swing with significant impacts, but it wasn't socialism by any measure. It was simply politicians whose egos got beyond their intellects. The chaos of that time was hard to endure, but we survived.

I too lived through all that, trying to get a home when interest rates peaked at over 23% and young kids. But making sure the people of the country can afford to live is common sense. Socialism is giving them a free ride off someone else's earnings.

Murray. 'ignoring the needs of the people of the country ... is done so at the risk of your power and influence'. Is it though? There are multiple examples of NZ govts making drastic change without mandate and not suffering particularly at the hands of electors. Successive Nat & Lab administrations imposed mass migration on the country without consultation. The Ardern govt forced a wave of indigenisation on institutions. You could argue the 2023 result reflected an element of push back against the latter but largely NZrs passively accept being strong-armed by the ruling elites.

And what was the outcome of the example you gave JA jumped ship before the end of her second term. To be fair though she saw the country through some extreme times that had not been seen for decades, where there was no societal memories of what was needed.

But again they tried to introduce racial division as a way to entrench their power and privilege and it didn't work.

The lobbying of government is a concern and needs at least to be transparent so the public can debate the need.

Don't you find our national obsession for strong leadership just a bit frightening?

I know I do, and I'm not sure about what it says about our national character.

CTs proposition that a state run insurer managed by govt appointed stooges could effectively compete with the likes of privately owned Tower is nostalgia invokingly quaint. The underwriting business has drastically changed since the heyday of the inefficient behemoth that was taxpayer subsidised Sate Insurance of old. Look no further than the shambolic performance of state owned insurer EQC during the ChCh EQ sequence for a reference. It's not co-incidental that its Natural Hazards Commission successor has outsourced much of its claims function to private enterprise.

really? Today's insurers are profit focussed and insurance is widely recognised as becoming increasingly unaffordable. Why wouldn't a state owned insurance company with the mandate to learn all the lessons and apply them be made to run efficiently?

You mean like our councils do

Don't understand do you. Council are local government, not a business. Big difference.

Murray. In theory yes but it rarely happens that way. One part of me would enjoy watching hapless bureaucrats have a go at taking on the market. As we saw in ChCh, get general insurance wrong and you quickly lose not just your shirt but your whole wardrobe. It's a simplistically unprovable assertion to state that eliminating the profit focus would make general insurance more affordable.

All the counter arguments tend to be on the extreme.

Why wouldn't any new insurance company established today be able to succeed?

Take for example the commercial model; your premiums have a component in that attributes to 1:1000 year risks and the likelihood of such a risk being realised this year. But if it doesn't get realised, the unpaid premium is paid out to shareholders as profit, not salted away to be built up to cope with those rare, significant risks when they do happen (such as Christchurch). Take away the demand for profit to be filtered off, and you have the potential to build a capital reserve that is genuinely capable, in time, of coping with major events.

The problem is not who owns the company but how it is run, as always, irrespective of the owner. Yes governments have a poor record of putting 'Yes men' in charge and messing with the model, but why assume that will always happen? Why not place criteria around what is required to make it succeed?

only benefit i could see would be ability at state level to issue disaster bonds.

whats an example of a great gov business to model it on?

even banks have sold their insurance business.

What insurance company model is worthy to copy? Perhaps the only one, is the one CT cites in his article which was entirely successful.

'State insurance entirely successful'. Perhaps in its early days but during the latter part of its life it was a long way from that.

what changed to make it less succesful?

Understand that and you find the answers you seem to be avoiding.

I'd have to say that it was easy to insure houses when there was plenty of native timber to plunder and rebuild them. The cost of resources are higher now, therefore the risk is higher in a mass weather event or natural disaster. How can you build like for like if your home is made of 600+year old heart Rimu?

Today there is an abundant supply of treated pine to build houses from. The insurance issue is about having to adapt to modern, available materials for the most part. If you are insuring a very old mansion with a historic rating then the risk premium would necessarily have to be higher if the requirement was to replace rimu for rimu or matai for matai, if it was even possible.

Murray. That 1:100 year catastrophe risk is largely funded by reinsurance for which retail insurers pay a yearly premium. If the cat cover is not utilised in any given year it's the reinsurers who capture the profit, not the insurer nor shareholders. Insurers can make a profit in a low claims year on the much smaller primary layer they retain to their own account below the activating trigger point for the cat layer. Part of this surplus is retained as reserves with the rest going as profit to the bottom line. It would take a very long time and a huge amount of good luck for a not for profit insurer starting from scratch to build up sufficient reserves to cover its entire (including catastrophe) exposure. Not going to happen in our tiny but high natural hazard market.

It doesn't really matter that the premiums are soaked up by the primary or secondary layer. What matters is that they are profit focussed at the expense of their customers and communities. As has been reported recently insurance company profits are growing, and it is suggested that to a lesser degree their capital reserves are too.

But it needs to start somewhere. As their capital reserves grow, they have less need for reinsurance, reducing their costs, thus increasing the rate their reserves can grow. To say it would take a long time to build the reserves is not an excuse for not doing so. As to luck - the entire industry is about balancing risk and luck.

A return to the past is not the solution...we need to develop an economy that addresses the reality that (real) growth is no longer the goal nor available.

If a large number of citizens remain trapped on Levels 1 and 2, however, no government should feel secure.

“When there is not enough to eat, people starve to death. It is better to let half of the people die so that the other half can eat their fill.”

Famines and food scarcity remain important reference points in Chinese political discourse, often cited as demonstrations of policy failures or as cautionary lessons in governance.

The March for Australia perhaps an indicator of how the hoi polloi are feeling.

You really know you made a bad policy decision when a decent % of your population starve to death. Luckily we have KFC here if you forget to complete your census forms, or are feeling peckish during NRL games....

After 2 years of total economic stagnation the Keynesians are all, belatedly, emerging from under their rocks to remind us that 'there is an alternative'. But, sadly for NZ, the full capacity of a fiat currency issuing state is never allowed to undermine the 'real' private sector economy by highlighting just how unnecessary it is.

The electricity sector is another example of a former public sector utility which now pays billions in dividends for an industry that has no physical competitive market and has to be regulated in such a way so we can make believe that it does.

Its a complete mess and we have 11 years of gas left with which to transition.

It would be wise to have a Solar and or Wind backup on your property...

Always was.

But the inevitable reduction in FF isn't just about personal electricity...

If the research of the American psychologist Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) is to be believed, humanity’s interest in great causes and grand schemes becomes politically decisive only after its individual members enter the upper stages of his famous “hierarchy of needs”.

Describes the Greens and their demographic in a nutshell. Problem is, they think (or believe) they represent the norm.

There proposed economic policy would see a transformational lift in living standards and opportunity for young people and upcoming generations - in particular. The levels of direct, large scale engagement by the government in the NZ economy would be similar to the post-WW2 growth and prosperity that enabled ordinary, working class Kiwi's to own property and raise a family with access to free education and healthcare - for the first time ever in human history.

public sector debt = private sector surplus - because the government creates new money and with it cost-free or reduced-cost services to the private sector. When the government reduces the amount of debt it carries, the private sector has to increase its debt or go without.

It's not about debt at this late stage in the game; it's about resources and the number of people competing for what's left of them.

And yet so many choose to ignore that fact.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.