This a speech the Governor of the Reserve Bank gave to delivered to Business Canterbury in Christchurch on February 20, 2026. The original is here.

It is a pleasure to be here today. I would like to thank Business Canterbury for inviting me to speak to you all. This is my first time in Christchurch, and indeed in New Zealand’s South Island. I am already impressed by your lively and scenic city. I know that Canterbury went through a very challenging period following the earthquakes. But you have rebuilt and emerged as one of the bright spots of the New Zealand economy today. I am keen to meet with you and learn more about your region and its economy.

Being Reserve Bank Governor comes with a profound sense of responsibility, because the decisions of the Reserve Bank have such wide-reaching impacts for New Zealanders. My focus as Governor will be on the Reserve Bank’s core mandates. For monetary policy our mandate is very clear: we’re tasked with keeping inflation low and stable.

Today, I want to focus on the need for monetary policy to be forward looking. This is important for three main reasons. First, it takes time for changes in the Official Cash Rate (OCR) to influence the economy and inflation. Second, economic data are often highly volatile and lagged. And third, forward-looking policy helps financial markets adjust to new information.

In practice, this means we base our monetary policy decisions on a forecast of where inflation is heading, and not on where it is today. But importantly, we learn from incoming data and adjust monetary policy as we go so that inflation converges to the target. So, being forward looking does not mean that monetary policy is on a preset course.

Our current situation is a good example of the need to stay focused on the future. With inflation slightly above our target range, how do we ensure that inflation will return sustainably to target without stifling the nascent economic recovery? But before I explain our latest decision, let me highlight why low and stable inflation is so important.

Keeping inflation low and stable is the best contribution monetary policy can make to helping New Zealanders

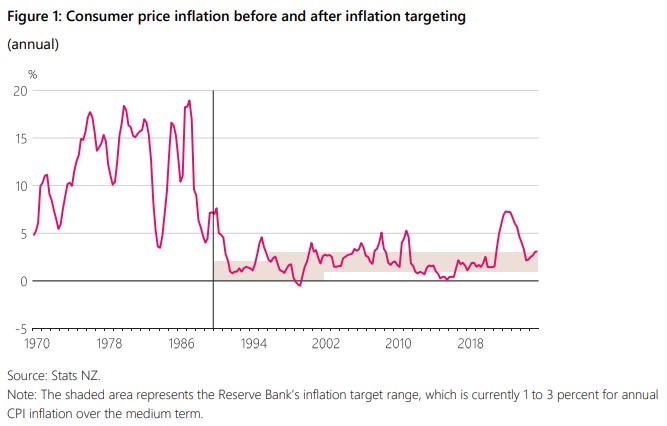

The 1970s and 1980s show us what can happen when monetary policy does not have a clear focus on price stability. Before 1990, the government could direct the Reserve Bank in setting monetary policy, with policy settings often directed at boosting growth and employment.2

What’s the problem with that? You could sometimes use monetary policy to give the economy a short-term rush. But what New Zealand got in this period was very high inflation with no enduring improvement in growth or employment (figure 1). Volatility in inflation and real incomes uncertainty for people and businesses trying to plan for their futures.3 Average weekly earnings were largely stagnant in inflation-adjusted terms over the 1980s.

In 1990 the Reserve Bank was given clear responsibility for price stability, and independence to decide New Zealand’s monetary policy. Since then, New Zealand has enjoyed much lower inflation. Of course, other factors – like globalisation – helped keep inflation low too. But having an independent central bank focused on price stability has been key.4

Low and stable inflation makes it easier for households and businesses to make decisions and plan for their futures. It helps ensure that New Zealander’s incomes and savings aren’t eroded by rapidly rising prices. And it supports healthy growth, with a strong labour market and growing real incomes.

In recent years New Zealand, like many other countries, has experienced the pain of high inflation for the first time since the 1980s. Even though inflation has fallen since the peak in 2022, many households and businesses are still feeling the effects of several years of high inflation and weak growth. How do we ensure inflation returns sustainably to target without stifling the nascent economic recovery?

Monetary policy decision: New Zealand’s economy has room to recover while inflation falls to 2 percent

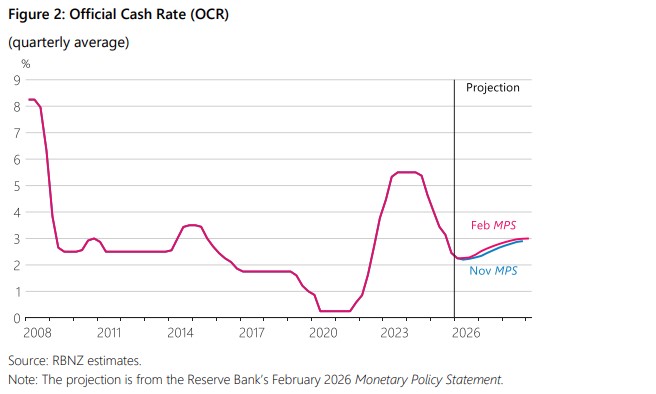

This week, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to leave the OCR unchanged at 2.25 precent (figure 2). The Committee emphasised that an economic recovery is underway, and that there are signs of it broadening across the economy. Inflation is slightly above our target range at 3.1 percent. However, we are confident that inflation will return to the target midpoint over the next 12 months. Let me explain how we used our future-focused Remit to guide our decision before I get into the details of the outlook for the New Zealand economy and inflation.

We must understand the present, but look ahead to the future

I want to stress that we are never comfortable having inflation outside our target range. But we must accept what has already happened, understand it, and then look ahead.

That’s what our Remit asks of us: that we focus on future inflation.5

This makes good sense. Let me give you three main reasons for this.

Monetary policy takes time to impact the economy

First, our monetary policy decisions take time to flow through to inflation – about 6 to 9 quarters for the peak impact.6 Increasing the OCR now would not bring inflation down immediately. But it would hamper the economic recovery. And if the recent increase in inflation proved temporary, we would risk undershooting our inflation target.

Economic data are often volatile and lagged

Second, economic data can be highly volatile.7 For example, for the first three quarters of 2025 New Zealand’s measured economic growth fluctuated between strongly positive and strongly negative.8 This volatility reflected many factors – including fluctuations in the timing of agricultural production, changes in energy supply for manufacturers, and changing seasonal patterns.

Inflation is constantly pushed around by temporary changes in the prices of global commodities and services, as well as fluctuations in domestic energy prices and the ‘one-off’ effects of some central and local government policy changes.

If we reacted to short-term economic volatility, we would simply add to it. Instead, we aim to understand what each new piece of data tells us about the fundamental drivers of inflation, and whether it represents a new trend or temporary volatility

In reality, this is challenging, particularly in times of great uncertainty.9 In such circumstances, it may be better to publish several alternative scenarios instead of a central projection. For example, in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic the Reserve Bank published three scenarios instead of a central projection. Similarly, the Bank of Canada switched to publishing multiple scenarios for a period following US announcements of higher tariffs in April 2025.

But even in more normal times, it is a challenge to stay focused on the future when our data are always behind us. Our latest inflation and unemployment data are for the last three months of last year, while our latest GDP data are even older, covering July to September of last year.

Forward-looking policy helps financial markets adjust to new information

Third, focusing on the future helps financial markets anticipate how the MPC will react to new information about inflationary pressure. This allows financial conditions to change in response to new data – in a way that helps us to achieve our mandate – even before the MPC has met to consider the new data and adjust monetary policy.

To support this, the Reserve Bank publishes a forward-looking track for the OCR, in combination with economic projections, and a discussion of the main risks to our assessment.10 Publishing alternative scenarios more regularly can be considered to further help markets understand our reaction function.11

Of course, given volatility in the economic data, financial markets can react strongly to movements in the data that turn out to reflect temporary factors, rather than fundamental changes in economic conditions.

With that said, let me go into how understanding the present but looking ahead to the future is relevant for our current monetary policy stance.

An economic recovery is underway, and there are signs it is broadening across the economy

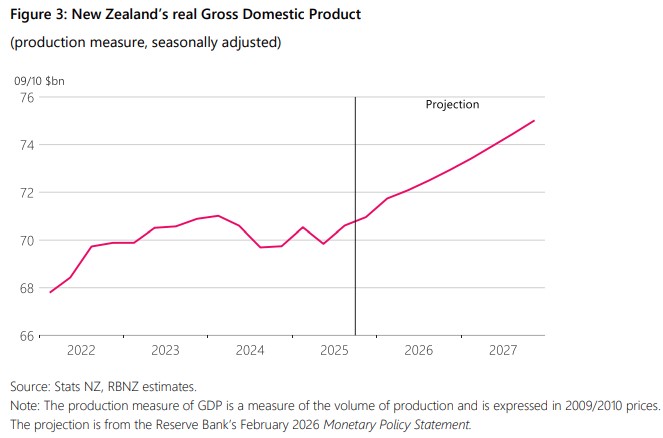

The economy is at an early stage in its recovery. With ongoing strength in commodity prices, economic activity in the agricultural sector and regional New Zealand remains strong. In response to lower interest rates, economic growth is broadening across sectors of the economy, such as manufacturing, construction and some retail. The chill from the surge in uncertainty about tariffs last year has partly abated.

New Zealand’s economy expanded in the September quarter last year, and our indicators point to an ongoing recovery into the end of 2025 and the start of 2026 (figure 3).

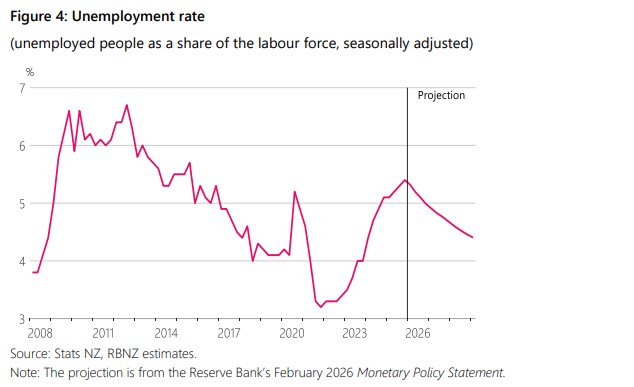

As for the labour market, unemployment remains elevated, and wage growth remains subdued (figure 4). But there are signs that the labour market is beginning to stabilise. The labour market often only improves once employers are confident business really is picking up, which we expect will happen this year.

Just like the downturn, the recovery is likely to be uneven. We have already seen stronger growth in exports, business investment, and house building, compared to relatively subdued growth in household consumption. I will hear today about how the recovery is going in Canterbury, and I’m looking forward visiting other regions to hear what’s happening there.

The path has been bumpy, but inflation is expected to return to our 2 percent target midpoint over the next 12 months

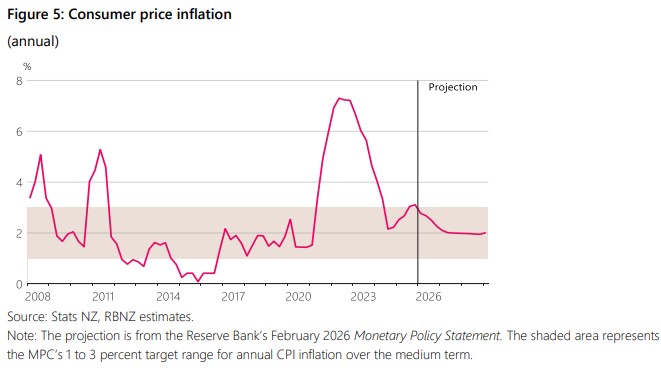

The path lower for inflation has been a bumpy one. Annual consumer price inflation fell from its post-COVID peak of 7.3 percent in mid-2022 to 2.2 percent in the second half of 2024. It increased over 2025 to 3.1 percent in the December quarter of last year, which is just outside our 1-3 percent target range. However, we expect inflation to be back in our target range now in the first quarter of this year and to return to our target midpoint over the next 12 months (figure 5).

This judgement is a critical part of the MPC’s forward-looking assessment and decision to hold the OCR at 2.25 percent. We needed to assess whether the recent increase in annual consumer price inflation is a sign of broader inflationary pressure, or just a temporary bump in inflation’s path lower.

Global factors have increased inflation for goods and services that can be traded internationally

Global factors are behind much of the recent increase in inflation in New Zealand. Many of the products New Zealand households consume can be bought on international markets. The prices we pay for these products – even the ones that are made here in New Zealand – are heavily influenced by prices in global markets.

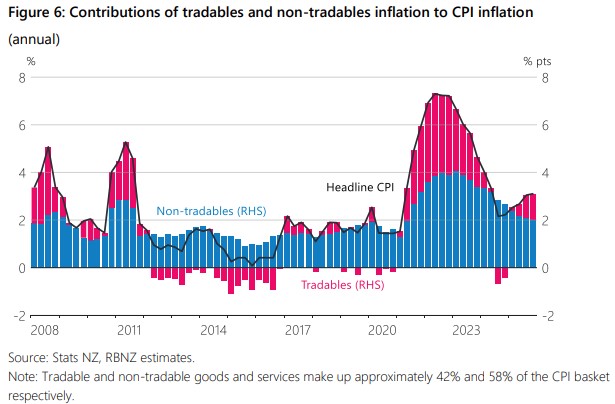

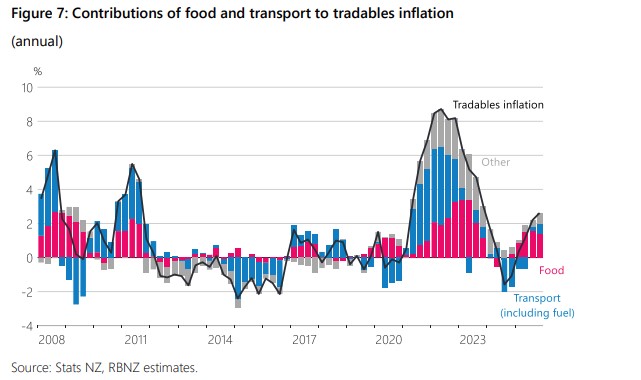

Inflation for tradables products picked up in 2025, after being negative in the second half of 2024 (figure 6). Rising inflation for tradable food and transport – which includes both fuel and airfares – explains much of this increase (figure 7).

Fluctuations in tradables inflation are common and often short-lived. Looking forward, tradables inflation is expected to fall back over the next 12 months given relatively stable import prices and some support from the recent appreciation in the New Zealand dollar.

Non-tradables inflation has been declining, but only gradually

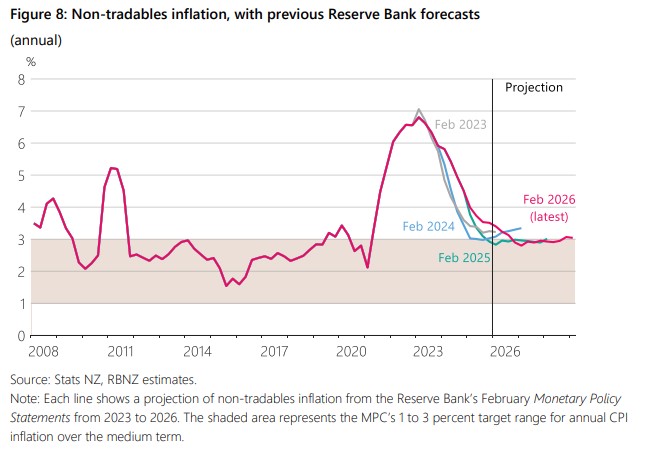

What about goods and services that aren’t exposed to global volatility – such as housing and local services? Prices for these ‘non-tradables’ are driven much more by what’s happening here at home. Non-tradables inflation has been declining since 2022, but it has been a slow grind lower, and non-tradables inflation has proven more stubborn than expected by the Monetary Policy Committee over the past few years (figure 8).

The decline in non-tradables inflation has predominantly been driven by weak demand in the economy. When demand is weak, people and businesses compete less for goods and services and productive inputs, and inflationary pressure in the economy falls.

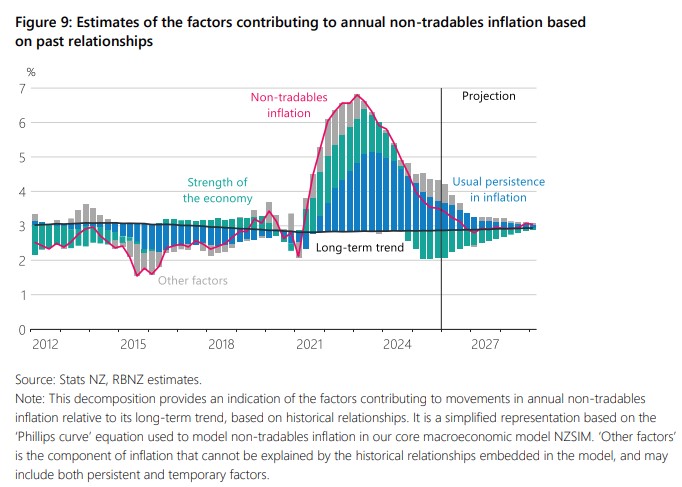

This has been the case in New Zealand over the past two years – weak demand in the economy has kept a lid on these pressures (figure 9, green bars). Weak demand is expected to continue to pull non-tradables inflation down over 2026, but by less and less as the economy recovers.

With weak demand in the economy, why hasn’t non-tradables inflation fallen faster? In other words, why has non-tradables inflation been so persistent? An important reason for this is that the pricing decisions of firms and workers have been slow to adjust back to a low inflation environment.

When inflation is high, businesses tend to increase their prices to catch up with or get ahead of rising input costs and workers try to negotiate higher pay rises, so the purchasing power of their incomes does not fall behind. These decisions add up to keep inflation higher for longer, with persistent effects that can be felt for years.

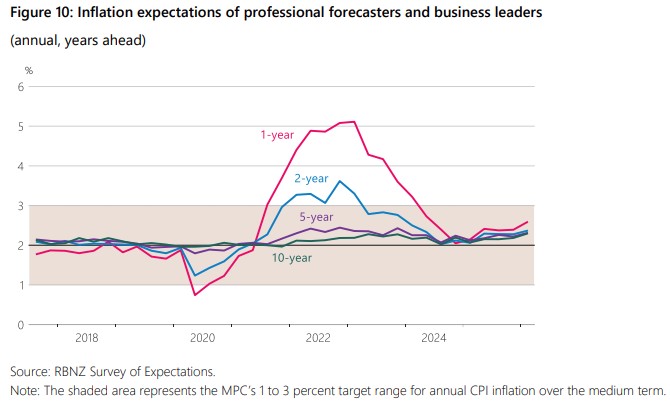

We think this process has been slowing down as headline inflation has declined, and that it will slow further as households and businesses continue to adjust back to a low-inflation environment (figure 9, blue bars). Consistent with this, expectations for future inflation are well within our inflation target band (figure 10).

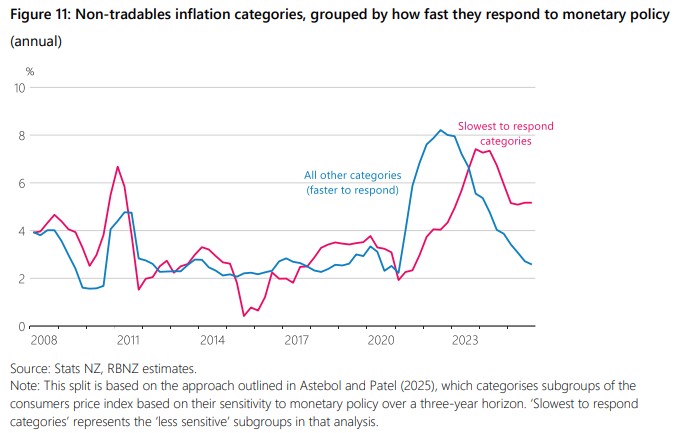

Another key reason why non-tradables inflation has been higher than expected over recent quarters is that prices for some categories of non-tradables products have continued to increase even though demand in the economy has been weak (figure 11).12 Eventually, prices for these products will respond to the lower inflation environment.

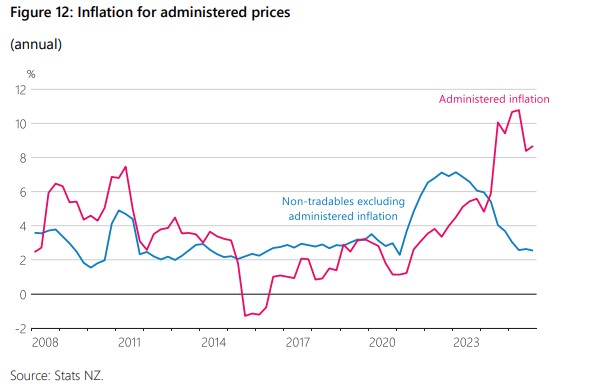

Lastly, administered prices – which are prices more directly influenced by central and local government policies – have been increasing strongly over recent quarters, adding persistence to non-tradables inflation (figure 12).

For example, council rates have been increasing more quickly than overall inflation, and it is unclear how long this will persist. But other recent drivers of administered price inflation – like those from increased electricity lines charges and changes to fees free education – are expected to exert less upward pressure on inflation over 2026.

Underlying inflationary pressures are lower than headline CPI inflation

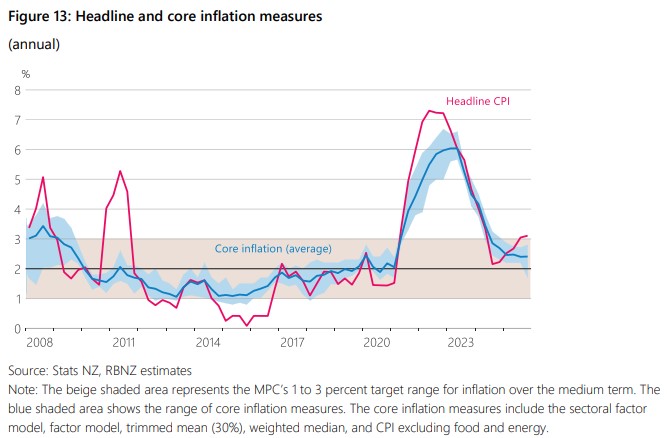

There are always various factors influencing inflation, making it harder to discern the underlying trends. We need to look into the details. We also have tools that help us to step back from the details to get a feel for underlying inflationary pressures in the economy. These tools produce measures of ‘core inflation’ that strip out or put less weight on prices that tend to be volatile. Currently, our measures of core inflation are telling us that underlying inflationary pressure in New Zealand is not as high as the headline CPI suggests (figure 13).

Core inflation being stable and within the target band is consistent with our forecast for inflation to fall over 2026.

Summary

New Zealand’s economy has room to recover while inflation heads towards 2 percent

What does all this mean for 2026? We expect declining tradables inflation to bring New Zealand’s inflation rate back within our target range, while the more persistent inflation pressures continue on their gradual path lower. This will provide the New Zealand economy with room to further recover, without a lift-off in inflation.

That is a positive outlook for 2026. But it doesn’t mean we can put our feet up. Forecasting inflation is never easy – we have thought of many ways in which we might be wrong. And today’s volatile world only promises to deliver more curve balls. You only have to look at the growth in artificial intelligence and the major shifts in geopolitical relationships to know that the world is changing. The transition is unlikely to be a smooth one. Eyes on the horizon: Looking ahead in a volatile world 13

Risks to the inflation outlook are balanced, but monetary policy is not on a preset course

Importantly, being forward focused, as I’ve discussed, does not imply that monetary policy is on a pre-set course. We will adjust our plans as we get new information, and always with a focus on the future.

I recently learned a Māori whakataukī: Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua. It’s about looking back and reflecting so you can move forward. And that’s exactly what we do. Our experience of the past – of economic cycles, of unexpected shocks, and of volatility in the data – helps us to understand what each new piece of data might tell us about the future.

We know that the economy will never evolve exactly as we expect. But we should strive to set policy for the future, to stay focused on the goal, and to not overreact to volatility in the data.

The Monetary Policy Committee has a clear mandate, to guide inflation back to target in all sorts of conditions. We will continue to look ahead and respond to what the world delivers.

Thank you.

Notes for this speech are in the original, which is here.

9 Comments

I am hopeful the diary sector will spend more money this year if export prices hold up along with payout from the consumer business sale. With the recent buoyancy in their incomes, I would assume they have strong balance sheets.

I think the dairy farmers are fed up with being blamed for climate change, water pollution etc. They realize the next political cycle will make them the scapegoat again. We forget they rescued our economy in 2009 and will forget this time as well. Bank risk profiles have been unfairly weighted against rural by the reserve bank. Hence rightly being very cautioua about spending.

100 % correct

Being fed up won't make the problems of climate change and water pollution go away. Dairy farming causes massive pollution of water ways and farmers need to work hard on changing their practices to reduce pollution e.g precision fertilizer application at times when heavy rain won't wash nutrients into waterways, lower stocking rates, and many incremental changes that move the both the dial and demonstrate improvements.

"Lastly, administered prices – which are prices more directly influenced by central and local government policies – have been increasing strongly over recent quarters, adding persistence to non-tradables inflation (figure 12).

For example, council rates have been increasing more quickly than overall inflation, and it is unclear how long this will persist. But other recent drivers of administered price inflation – like those from increased electricity lines charges and changes to fees free education – are expected to exert less upward pressure on inflation over 2026"

Was this said with a straight face? (given the recently released Infrastructure report)

Tokyo spends USD174 million a year to operate about 400 libraries.

NYC spend about USD500 million to operate 200 libraries.

Mamdani on Aug. 5, 2025 said: "As Mayor, I'll end this absurd budget dance that keeps our beloved libraries in limbo year after year."

On Feb. 17, Mamdani proposes $29.5 million in cuts for library budgets.

https://nypost.com/2026/02/20/us-news/mamdani-reverses-campaign-promise…

The positive spin from NZ economists is all about "looking through' the ongoing forecast stagnation in the NZ economy in 2026. But this from Breman pulls back the curtain just a little bit - "Weak demand is expected to continue to pull non-tradables inflation down over 2026". Unemployment is - now - expected to recover by mid 2027. That is a long, long time away.

Exactly. It keeps being pushed out each time they get it wrong.

Having read her speech my assessment is that Breman is astute and highly competent with top level analytical and communication skills which are definitely needed in increasingly uncertain times ahead. She is earning her salary and NZ is fortunate so far with her appointment.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.