The recent discussion around land use and what can be considered suitable land use in New Zealand got me curious to look at how sectors other than livestock systems are faring.

As one thing I am well aware of is the changing nature of land use when different economics and technologies appear. A classic case in my memory banks is what has happened to the Tairawhiti/Poverty Bay flats over the years. In my early years my recollection was large areas of maize being grown with maize drying racks scattered over the landscape. (When I returned to Gisborne in the mid-1990’s I spent some time with staff dismantling these and salvaging timber etc for other uses). Along with the maize, lamb finishing also took up a large amount of space.

At that time Gisborne also had a reasonably successful dairy industry. It had started as a butter based system (our then family farm was converted from butter dairy to sheep and beef in 1960) and moved into milk processing for ‘town supply’ with the surplus ‘going through the gorge’ to the Opotiki Dairy Company and beyond. However, by the 1990’s numbers of farms had declined and by 2013 closed, with the blame laid at the requirement for Fonterra to supply ‘cheap’ milk to competitors which undercut their market and by then also the number of dairy farms had greatly declined with the land going into intensive horticulture, as did much of the arable and lamb finishing land.

Even the horticulture had cycles of vineyards to kiwifruit back to vineyards with a combination of varying crops grown there now.

Of the 17,880 hectares of flat land surveyed in a Gisborne District Council 2016/17 (January data) report there are nine different land uses highlighted with pasture still making up the largest percent followed by maize and corn.

- Pasture 5,600 ha

- Maize and Corn 4,800 ha

- Grapes 1,700 ha

- Squash 1,480 ha

- Citrus 1,471 ha

- Kiwifruit 433 ha

- Pip and Stone-fruit 466 ha (these range from avocado to apples to persimmon to pomegranate and most things in between)

- Tomatoes 207 ha (there was nearly 700 ha not long ago)

- Fodder crops (chicory, plantain kale, lucerne, etc.) 488 ha

- Minor crops (melons, strawberries, feijoas, etc.) 200 ha (estimate)

- Nurseries 60 ha

- Processing vegetables 154 ha

Unfortunately, I cannot provide data of what was on the flats prior to the, lets say, 1980’s when land use change there really picked up, but my recollection is it was during the 80’s when lots of different crops were tried, often out of desperation to find something that would pay the bills (we had Nashi at Matawai until wiped out by a heavy hail storm, which probably saved us from a lot of later wasted effort).

My point here is there are no sacred cows when it comes to land use and also it doesn’t pay to be too fixed in your view about what can and cannot work as a productive income stream because things change.

Canterbury and Southland over the last two decades have obviously experienced widespread land use change and while they have largely remained in pasture, cows have replaced much of the sheep. However, as regulations have belatedly started to catchup with the development the expansion of dairying has not only stopped but begun to decrease.

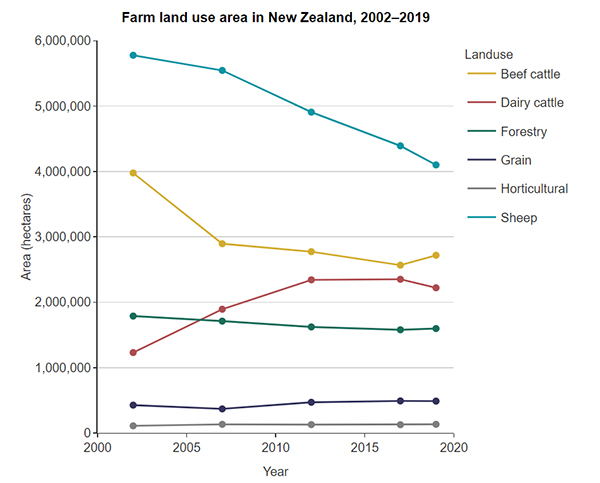

At the national level land under dairy farming is now at a similar level to what it was 10-12 years ago. Most of the decrease in my mind is due to the increased pressure regional councils have applied over water use and runoff but also as farmers find other land uses. Taranaki was the only province to show an expansion in dairying land area.

Source: https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/agricultural-and-horticultural-land-use (2021)

The other provinces generally have similar profiles to the national model shown above. Given that livestock systems have not had to ‘pay’ for their greenhouse gas emissions, the rate of change on land suitable will only speed up as and if these costs increase.

Many farmers will feel that any payment is unjust especially as most other countries do not have pay for their livestock emissions, and they have a point in my mind. The US despite signing up to reduce methane by 30% by 2030 appear to be not including livestock among those targeted to make the reductions. European countries also appear to have little in the way of policies directed to reducing livestock emissions. Having said that Ireland has a similar problem to New Zealand with 37% of its GHG emissions coming from agriculture and having also signed up to 30% reduction by 2030. It has been calculated they would need to reduce their 6.5 million cattle numbers by 1.3 million.

The quandary livestock farmers face here is that it appears any real mitigation or reduction techniques (not trees) are probably 10 years away for major reductions and the imposition of cost starts in 3 years.

So, do farmers hang in there hoping for the silver bullet (which may or not come) or perhaps a change in policy, although most of the major political parties have signed up to the reductions agreements?

Or, do they start to look at diversification options now?

Coming back to the South Island, remembering while wheat and barley are not natural to New Zealand, farmers here have managed to achieve world record production despite this. (Wheat: Eric Watson 17.4 tonnes per ha) and while the UK hold the current barley record it has also been held in New Zealand several times also.

This of course doesn’t mean there will be a wholesale switch to arable farming but the options are out there when the economics start to change and it does look as though that is on the horizon. Remembering also it was only a handful of years back when dairying was suffering from poor returns and rumours of the banks foreclosing on farms was rife.

P2 Steer

Select chart tabs

13 Comments

Imagine what NZ would look like if there was no cattle, sheep or chickens.

I'm not sure why people take it to the extreme , no one is talking about no livestock at all , seems a 30% reduction would be the worst case.

Takes me back to my school c geography studies in the late 70 's, though how up to date the books we were studying then were , I do not know . Coming form a pastoral farming area , i was surprised to learn how much arable crops were grown in NZ. Back then there were a lot of grains grown around Marton , as well as Canterbury .

I still think tree cropping for forage and other crops, is a method that could provide some benefit , if they allow the carbon in the trunk and roots to be counted. I also think it fair that city, industry and landfill waste be processed for Methane, already done in some places , but should be everywhere.

Agreed there has been considerable change in land use over the decades , I was involved in the development of the kiwifruit industry in the BOP in the eighties and it was an exciting time, as you say land use pretty much followed the money . This also occurred during the Muldoon era with the stock subsidies increasing land development and livestock numbers. With the onset coming of various carbon taxes and agriculture being responsible for in excess of 50% of our national emissions, but by a small percentage of the population this is going to be a difficult sell for the politicians. While carbon taxes impact the majority of people having their incomes and lifestyle impacted while a small segment of the population have their income and lifestyle unaffected as they are effectively exempt.

One notable feature of the Tairawhiti/Poverty Bay Flats, with these flats being modest in area, is that less than one third is in pasture. Some of that will have various cropping constraints relating to soils and flood risk. That illustrates that there is only modest scope for further cropping endeavours on land converted from pasture. Most recent crop development has been substituting one crop for another. History has also shown that it is not easy to make a lot of money out of cropping in this area.

Similarly, the history of Canterbury farming in recent decades has been of dairy replacing sheep on soils that have major cropping limitations. In contrast, the deeper soils have been used for mixed cropping for the last 100 years but there has been little appetite for cropping endeavours on the Lismore and Eyre soils. which are the dominant shallow stony soil types with low inherent fertility. With irrigation and lots of fertiliser, it is possible to grow crops on these soils, but the environmental challenges of crop-dominant systems are daunting.

KeithW

Doesn't dairy also require lots of fertiliser and irrigation on the same soils?

Yes, you are correct. But one should not assume that a shift to cropping on typical Canterbury soils will reduce leaching. Indeed crops such as potatoes typically leach considerably more N than does. dairying. And with dairying we are developing technologies and systems to greatly reduce the leaching.

KeithW

Yes, the competing sheds etc, are the way we need to move too.

I guess these soils are alluvial, I would think I increasing the carbon content would be advantageous, regardless of what is been grown/grazed.

Most Canterbury soils are loessial (wind blown silt) rather than alluvial. Most soils would have been low carbon in their natural state but would have built up under pastoral farming. Most of Canterbury was stark barren land prior to European settlement. There was no water for stock until the water races were built.

KeithW

Is there a particular volume of dairy you reckon Canterbury could sustain while still having clean waterways, drinking water, and sustainable aquifer levels for all users? Honest question.

Mmmm! That is tricky one. But I think it is technically possible to reduce N leaching to well under 10 kg per hectare on most soil types with composting structures, pivot irrigators, duration-controlled grazing, permanent pasture and no cropping. Would require using silage rather than fodder beet for winter feed. In other words, reducing N leaching by something over 75%.

KeithW

Keith

Composting barn benefits the environment has been well documented to the Ag sector yet to uptake is very low, this despite regulation that pushes farmers in that direction.

So it must be economics or work load that holding this tech back ?

Any thoughts ?

I was at a composting barn field day a couple of weeks ago with around 80 attendees. So there is interest.

One mainstream bank is keen but the others are still struggling with the concept.

Most dairy farmers are currently focusing on debt repayment.

I ran into one of my former students over the weekend. He is now dairying. We talked about the prices in his district being paid for dairy land compared to runoffs with significant leaching consents that dairy farmers can buy for wintering their cows. Runoffs with high leaching consents are now selling for more than developed farms. In contrast, runoffs without such consents are selling for less than half of those prices. It's a crazy world, but it illustrates that N leaching rules, albeit illogical, are starting to bite.

Coming back to the composting shelters and mootels, I am somewhat concerned that some of the structures are inherently flawed.

KeithW

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.