As US President Donald Trump proceeded to upend the world economy after his return to the White House in January, Nobel laureate economist Paul Krugman recalled Charles P. Kindleberger’s adage: “Anyone who spends too much time thinking about international money goes mad.” Fortunately, amid the Trump-induced chaos in the currency, bond, and stock markets, Yale University Press has recently published two complementary guides to a key aspect of international finance: the primacy of the US dollar.

Paul Blustein’s King Dollar and Kenneth Rogoff’s Our Dollar, Your Problem lead readers through recent economic history to assess the dollar’s current status and prospects. Both books were published after Trump’s re-election and, in Blustein’s case, before the opening salvos and subsequent escalation of his assault on the global economy. The timing is an opportunity to reflect on the past five months, in which – to paraphrase Vladimir Lenin – decades seem to have happened.

Full disclosure: Rogoff and I have co-authored more than 20 papers and a graduate textbook since 1983. Our intellectual collaboration began even earlier, when we were doctoral students at MIT in the 1970s. There, we encountered a very sane Kindleberger, as well as the young Krugman.

One thing we learned at MIT is that in macroeconomics, everything is connected. In international macroeconomics, those connections are global in scope. Understanding the dollar’s dominance today – and the likelihood that it will endure – requires a wide-ranging review of global economic and political developments, from the rise of payment technologies to the evolution of economic theory to shifting great-power relationships.

Accordingly, these highly readable books cover a wide range of issues. Blustein – a former Wall Street Journal and Washington Post journalist and the author of several acclaimed books on international financial crises – brings a seasoned reporter’s sensibility to the subject. Rogoff, for his part, draws on his experience as a world-class scholar and former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. He skillfully blends personal narrative with a compelling account of advances in international macroeconomics, a field he has helped define.

America’s Currency, Everyone’s Problem

The US dollar’s unique status today spans its roles as the leading reserve currency, investment and funding vehicle, and trade invoicing medium. As Blustein and Rogoff recount, the dollar’s postwar preeminence began with the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, which established the IMF and the World Bank. The special role of the dollar in the final agreement was apparently a last-minute change engineered by the United States – and a surprise even to most of the British delegation led by John Maynard Keynes. Still, given America’s military and economic dominance after World War II, dollar supremacy was inevitable.

The Bretton Woods system was a cornerstone of the postwar order. As economies recovered, international trade expanded under a framework of fixed exchange rates supported by generally prudent macroeconomic policies. Most countries pegged their currencies to the dollar, which served as the system’s anchor. The US, in turn, committed to redeeming dollar reserves held by foreign central banks for gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce.

In practice, this arrangement constrained other countries’ economic policies: lower interest rates than those of the US could lead to foreign-exchange reserve losses and pressure to devalue against the dollar, while higher interest rates could attract capital inflows and stoke inflation.

The US was far less constrained. It had broad latitude in setting monetary policy, provided it honored its gold commitment. But that required acting with conscious restraint, since instability at the system’s core would destabilise the entire global order.

Another significant asymmetry involved reserve holdings: most countries outside of the legacy sterling zone held a mix of gold and dollar-denominated reserves, while the US, as the issuer of the world’s leading reserve currency, held gold but had little need for foreign-currency reserves.

By the late 1960s, America’s role as the system’s responsible steward was becoming increasingly untenable. Rising fiscal pressures fueled inflation, eroded a once-commanding trade advantage, and strained gold reserves. While most countries could devalue their currencies, the US, as the system’s anchor, had to persuade its trading partners to revalue their currencies against the dollar. For then-President Richard Nixon, “persuasion” came in the form of a 10% import surcharge – to be removed once revaluation had been negotiated – and a unilateral withdrawal from the US gold commitment.

It was during the so-called “Nixon Shock” that Treasury Secretary John Connally famously told his G10 counterparts, “The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.” Connally’s candor was startling at the time, but, as both Blustein and Rogoff point out, there was nothing new about the US promoting its own interests by exploiting the dollar’s reserve-currency status. Blustein devotes several chapters to an illuminating account of how the US has leveraged the dollar’s global hegemony and the centrality of its banking system to impose crippling extraterritorial sanctions.

Within 18 turbulent months of the Nixon Shock, the world’s major economies had begun floating their currencies against the dollar – a system that remains in place today. Many predicted that the shift would mark the end of the dollar’s dominance and usher in a more balanced exchange-rate regime, where each country enjoyed independent monetary policies and no single currency prevailed.

In theory, such a system could eliminate the need for dollar reserves to manage exchange rates, yet countries continued to hold them as a ready source of international liquidity. After Nixon abandoned the gold standard, Kindleberger declared that the dollar “is finished as international money.” He was emphatically wrong.

Challengers to the Throne

The path forward was anything but smooth. As US inflation spiraled out of control in the 1970s, America’s trading partners chafed at holding their international reserves in depreciating dollars. The problem was that no viable alternative existed.

In 1979, the IMF’s leadership floated the idea of a “substitution account” that would allow member countries to exchange their dollar reserves for IMF liabilities denominated in special drawing rights (SDRs), a synthetic reserve asset valued based on a basket of major currencies. Created in 1969 to supplement the dollar in global reserves, SDRs have recently been distributed only during international crises, where they have been deployed effectively as an indirect way of helping poorer countries – a practice Rogoff criticises for lacking transparency, though some technocrats view that as a feature, not a bug.

The substitution account aimed to help countries diversify their foreign-exchange reserves while elevating SDRs to the status of “principal reserve asset in the international monetary system,” a goal enshrined in the IMF’s revised Articles of Agreement in 1978. But one major sticking point was determining who would cover losses if the dollar continued to depreciate, leaving the IMF holding the bag. Understandably, holders of dollar reserves wanted the US to absorb any losses caused by its weakening currency; not unreasonably, the US refused. The substitution account scheme subsequently collapsed. Our dollar, your problem.

What cemented the dollar’s dominance was a series of developments, starting with Paul Volcker’s appointment as chair of the Federal Reserve in August 1979. Volcker defeated inflation, establishing the Fed’s credibility by showing the central bank’s willingness – and political capacity – to engineer a deep recession to bring down prices. As Rogoff notes, central-bank independence became the dollar’s “bulwark of currency dominance.”

Next, financial deregulation laid the groundwork for US financialisation and reinforced the dollar’s primacy in international capital markets, which expanded rapidly as other countries – notably those in Europe and Japan – lifted capital controls. Finally, unprecedented current-account deficits attracted foreign capital to the US, while unusually high budget deficits supercharged the dollar’s foreign value and provided the world with an ample supply of relatively safe US Treasuries.

As global financial markets expanded, so did the need for a reliable medium of exchange and a safe asset. The dollar was uniquely positioned to serve both roles. Despite the large budget deficits of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, the US debt-to-GDP ratio was just over 40% when he left office – a level we can only dream of today. His successor, George H.W. Bush, eventually felt compelled to raise taxes, a decision that cost him a second term. By the end of his presidency, Bill Clinton achieved a budget surplus and left office with a debt-to-GDP ratio below 35%.

This brief period of fiscal probity solidified the dollar’s leading position. Worried that a weakening dollar could reduce global demand for US Treasuries and drive up the government’s borrowing costs, Clinton’s Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin introduced a “strong dollar” policy in 1995, causing the greenback to soar to the point where some commentators (including Rogoff and I) feared it might crash. While the dollar eventually declined significantly, the process was gradual, coinciding with a widening US current-account deficit. These developments culminated in the global financial crisis of 2008-09, which – though traumatic – proved to be another false alarm about the dollar’s impending demise.

The euro, introduced in 1999 and initially seen as a potential claimant to the dollar’s throne, remained a distant second throughout the 2000s as countries around the world continued to bulk up on dollar reserves. The 2009-12 eurozone crisis underscored the greenback’s seemingly unassailable advantages.

As both Blustein and Rogoff observe, potential challengers to the dollar have consistently come up short. The renminbi is no exception, despite China’s progress on its central bank digital currency (CBDC), the e-CNY. Rogoff’s exceptionally detailed analysis of the contenders even covers the Soviet Union, whose remarkable postwar growth made it an economic and military superpower into the 1960s.

Rogoff highlights a crucial point: greater exchange-rate flexibility is a prerequisite for the renminbi to mount a serious challenge to the dollar. But such flexibility must be accompanied by broader reforms in China’s financial markets and monetary policy framework. Although some exchange-rate adjustment may be underway in response to Trump’s exorbitant tariffs on Chinese imports – 124.1% as of April 12 – the prospect of a more open capital account appears increasingly distant.

Hegemony in Retreat?

The dollar’s international dominance is reinforced by powerful network effects: everyone uses it because everyone else does. Krugman modeled this dynamic decades ago, just as the dollar was solidifying its global status. As international financial markets and trade expanded, stronger reinforcement mechanisms emerged to drive demand for dollar-based currency trading.

The growth in currency trading has been dramatic. According to the Bank for International Settlements’ latest triennial survey, over-the-counter foreign-exchange turnover reached $7.5 trillion per day in April 2022, with the US dollar on one side of 88% of all trades. By contrast, the BIS’s April 1989 survey recorded a daily turnover of just $500 billion (though fewer central banks were polled at the time). Despite the strong network effects implied by such vast markets, however, economic models suggest that a single dominant currency is not the only possible outcome; scenarios involving multiple leading currencies also remain plausible. What Ernest Hemingway said about bankruptcy and MIT professor Rudi Dornbusch said about financial crises applies here too: change is likely to come gradually, then suddenly.

Blustein and Rogoff agree that several factors underpin the current equilibrium, in which the dollar remains the world’s only true international currency. These include America’s deep and open financial markets, openness to trade, a strong commitment to the rule of law, an efficient court system that protects even foreign creditors’ rights, a track record of price stability, and a robust supply of relatively safe benchmark assets. Another important factor is sheer economic size: the US economy accounts for roughly one-quarter of global GDP at current exchange rates, well ahead of China, the second-largest economy.

Rogoff emphasises the importance of America’s military and geopolitical reach in sustaining the dollar’s dominance. One could add soft power, which reflects the country’s willingness to provide global public goods. Issuers of potential rival currencies have repeatedly fallen short in one or more of these areas. That said, the bar for becoming a regional international currency is lower.

Listing the dollar’s strengths also underscores its potential vulnerabilities. Both Blustein and Rogoff worry about America’s fiscal dysfunction and the long-term implications for macroeconomic stability. They rightly argue that higher real interest rates, which may persist or even rise in the coming years, increase the risk of budget pressures. That, in turn, could undermine confidence in the safety of US government liabilities or trigger a policy shift toward financial repression.

More alarming still, the days when the US took its fiscal deficits seriously appear to be over. We can no longer assume that Congress will rein in deficits without the pressure of a financial crisis. As Alan J. Auerbach and Danny Yagan have shown, until the early 2000s, Congress typically responded to projected deficit increases by cutting spending, but that is no longer the case.

Despite many caveats and qualms, Blustein remains largely upbeat about the dollar’s future – or at least he did as of late 2024. “Whether you approve of dollar dominance or not,” he writes, “doubts about its durability should be put to rest.”

Rogoff, by contrast, is more open to the prospect of a regime shift. In his view, the dollar’s dominance has long depended on a considerable amount of luck, and luck has a way of running out. “There are many reasons to believe the Pax Dollar era has peaked,” he writes, observing that “the greatest dangers” to the dollar’s supremacy “come from within.”

Both authors penned final reflections as their books went to press in the wake of the 2024 US presidential election. Rogoff observed that asset markets appeared incongruously complacent despite mounting risks – no surprise to the author (with Carmen M. Reinhart) of the celebrated 2009 book This Time Is Different. Meanwhile, Blustein highlighted the growing danger to America of self-inflicted wounds, warning that if those risks materialize, “dollar dominance will be lost or diminished,” which “will be the least of our worries.”

Trump’s War on the World Economy

What, then, is the outlook for the dollar in 2025? As the title of Rogoff’s book suggests, the US has long pursued its own agenda. But it has typically done so within a broader conception of self-interest that recognized its own stake in an ordered, somewhat cooperative multilateral economic system. In 1993, political scientist G. John Ikenberry described the traditional American approach to postwar multilateralism:

“American officials realized that building the international economic order on a coercive basis would be costly and ultimately counterproductive. This is not to say that the United States did not exercise hegemonic power; it is to say that there were real limits to the coercive pursuit of the American postwar agenda.”

Such self-restraint is notably absent from Trump’s grievance-laden worldview. It seems fair to say that the sweeping radicalism of his administration’s policies has gone beyond even what Blustein and Rogoff could have foreseen in December 2024.

Trump’s policies are steadily undermining the foundations of the dollar’s global dominance. His withdrawal from international organizations and agreements, cuts to foreign aid, and transactional approach to US security commitments have unsettled allies and rivals alike. Domestically, his pressure on the Fed, weaponization of the Justice Department, efforts to gut the federal workforce at the cost of key governmental functions, and incursions on the institutional fabric of American society – from universities to judges to the legal profession – have further eroded confidence. Then there’s his trade war, unprecedented in its scale, capriciousness, and economic illiteracy.

At the same time, fiscal dysfunction has reached new heights. Congressional Republicans, encouraged by the White House, are preparing to increase the deficit by bypassing the traditional reconciliation process and relying on uncertain tariff revenues. This, too, signals deepening institutional decay – and markets are taking notice.

One area of concern is international collaboration on financial oversight. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the Financial Stability Board are essential to cross-border regulatory cooperation, but global regulators now worry that the US will approach these forums through the same zero-sum lens it has applied elsewhere – or withdraw from them altogether. Others have raised concerns about the reliability of the Fed’s dollar swap lines, a central pillar of dollar dominance that Rogoff explores in detail.

Eroding trust could accelerate the fragmentation of international capital markets, putting the dollar’s global standing at even greater risk. International regulatory cooperation is also critical to realizing the potential of decentralized finance to improve payment infrastructure – especially cross-border systems, which remain slow and costly. Without harmonized standards, diverging national approaches would severely limit interoperability and any resulting efficiency gains.

But the Trump administration’s embrace of untethered cryptocurrencies, resistance to oversight of crypto-related payment platforms, and executive order banning “any action to establish, issue, or promote CBDCs within the jurisdiction of the United States or abroad” risk isolating the US from advances in global payment infrastructure. This is a formula for undermining US integration with the global financial ecosystem – to the dollar’s detriment.

Perhaps, despite his protestations and threats, downgrading the dollar’s status is the real goal. Stephen Miran, chair of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers, has argued that the dollar’s global role “has placed undue burdens on our firms and workers,” making American goods and labour “uncompetitive on the global stage and forcing a decline of our manufacturing workforce by over a third since its peak.” As I have written elsewhere, this view far overstates the net “exorbitant cost” of providing the world’s reserve currency, while ignoring the considerable benefits to America’s global influence that Blustein documents at length.

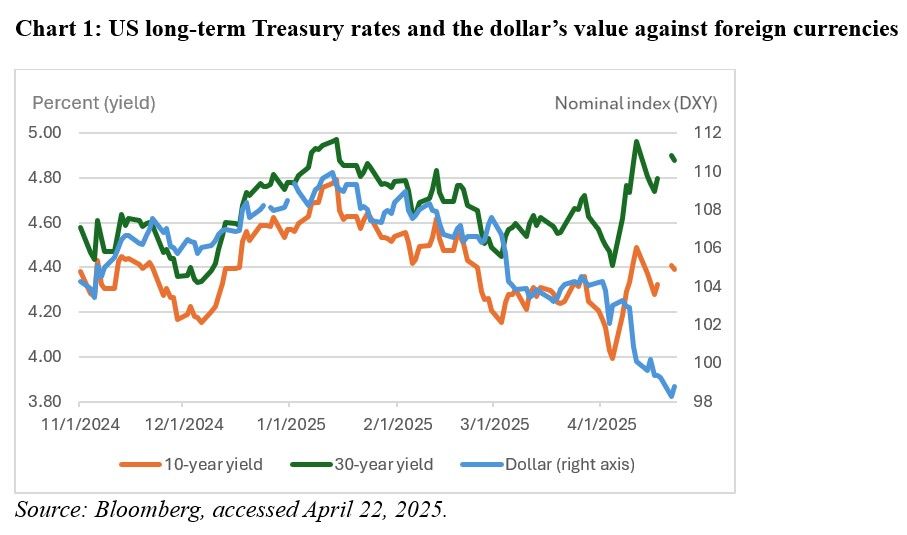

Since the escalation of Trump’s trade war with his April 2 “Liberation Day” tariffs, bond and foreign-exchange markets have been flashing warning signs. Chart 1 tracks ten-year and 30-year US Treasury yields alongside the dollar’s nominal effective exchange rate since just before the 2024 election. Through early March, both behaved as they do in normal times: higher yields attracted foreign capital, strengthening the dollar. But then, amid daily tariff announcements and partial reversals, the dollar fell sharply, recovering only slightly in the following weeks.

The greenback took another hit soon after Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs. Treasury yields spiked and the currency fell, signaling a global selloff of US government bonds due to reduced investor confidence in the quality of dollar assets. Trump’s reactive postponement of his so-called “reciprocal” tariffs briefly stopped the bleeding in equity markets, but markets and the dollar have fallen further in the face of Trump’s fulminations against Fed chair Jerome Powell.

The drama of recent weeks calls to mind the famous opening line of T.S. Eliot’s 1922 masterpiece The Waste Land: “April is the cruelest month.” As it happens, Eliot’s poem appeared during a particularly turbulent moment in international currency history – between the end of World War I and the brief, ill-fated return to the gold standard. The economic upheavals of the interwar era ultimately helped spur the creation of the US-led postwar system of global trade that Trump is now determined to dismantle.

To be sure, the dollar’s story is still unfolding. But the momentous events of this April may well signal a fundamental shift in the global trade order – and with it, the dollar’s ultimate dethronement. If that is the case, we may be headed for a future of currency fragmentation and diminished global prosperity, with no clear successor ready to take the dollar’s place.

*Maurice Obstfeld, a former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, is Senior Fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Professor of Economics Emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2025, published here with permission.

3 Comments

Great read. It's a lot to get your head around.

This is most important;

But the Trump administration’s embrace of untethered cryptocurrencies, resistance to oversight of crypto-related payment platforms, and executive order banning “any action to establish, issue, or promote CBDCs within the jurisdiction of the United States or abroad” risk isolating the US from advances in global payment infrastructure. This is a formula for undermining US integration with the global financial ecosystem – to the dollar’s detriment.

Could it be they are planning to debase the dollar on purpose as a means to herald in a crypto/token-based means of internal exchange? End the Fed, nationalize the banks and the Treasury controls all token issuance. They are all quite mad, you know.

Crypto may be a way for insiders to gain at the masses' expense.

As happened here in '84, with the instant devaluation which only some knew about.

But the bigger problem is the one Peter Shiff identified on the surface (but failed to identify the underwrite) in 'How an Economy Grow, and...". The US dollar hegemony is over - with massive ramifications for everyone in the First World, who placed digital forward bets on the assumption that they were underwritten...

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.