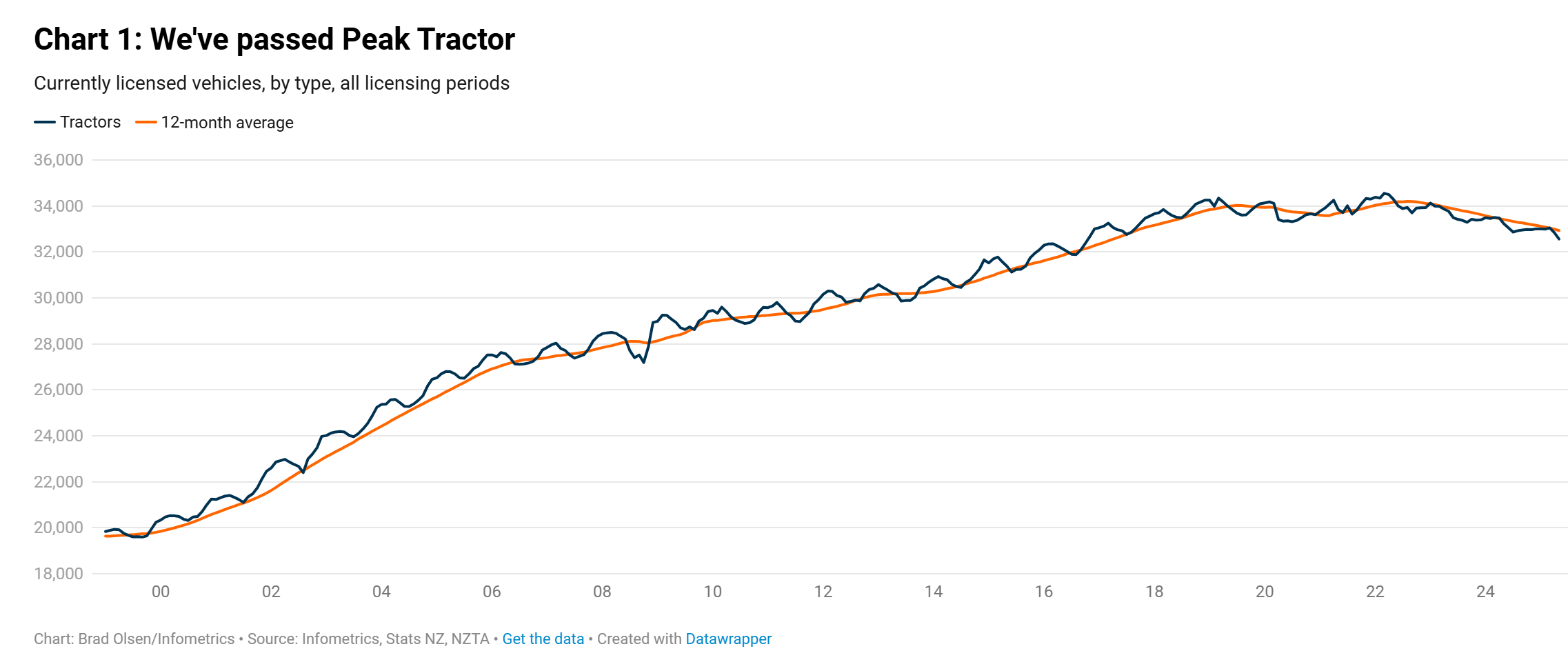

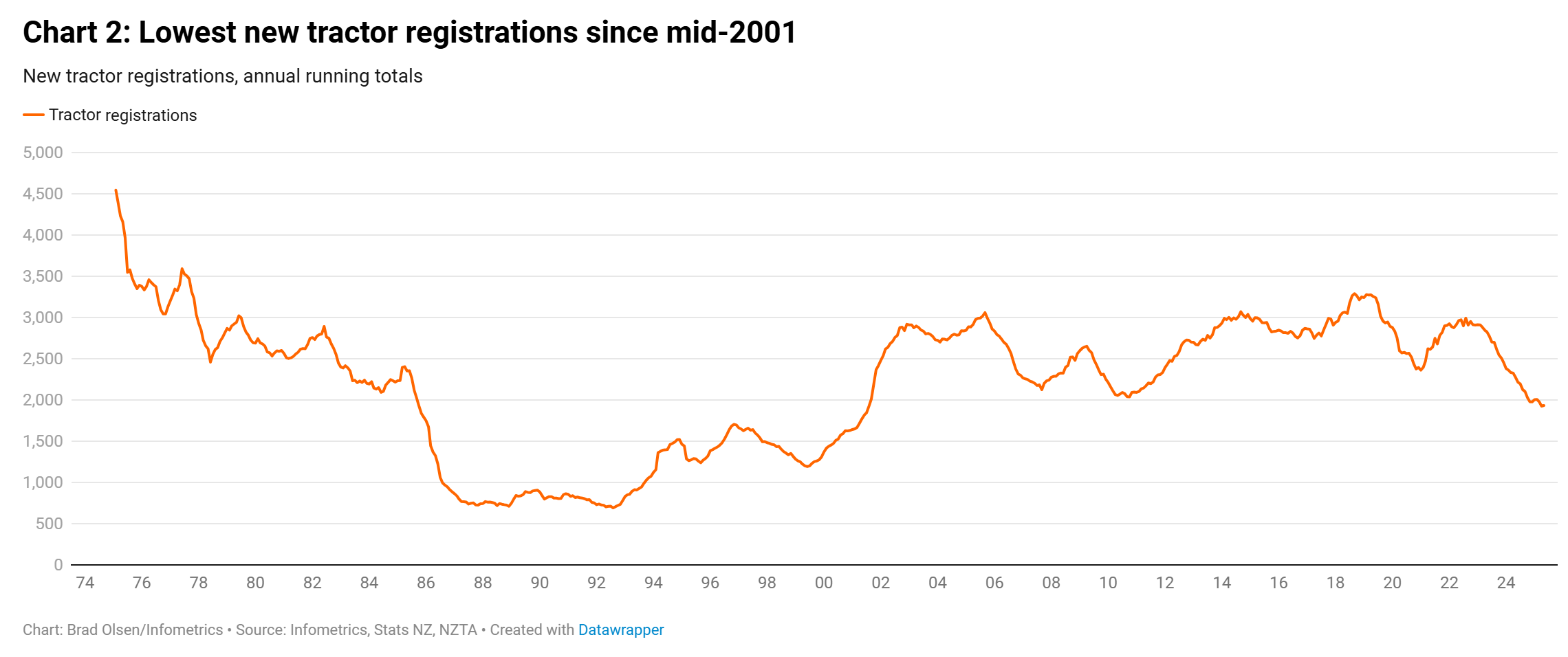

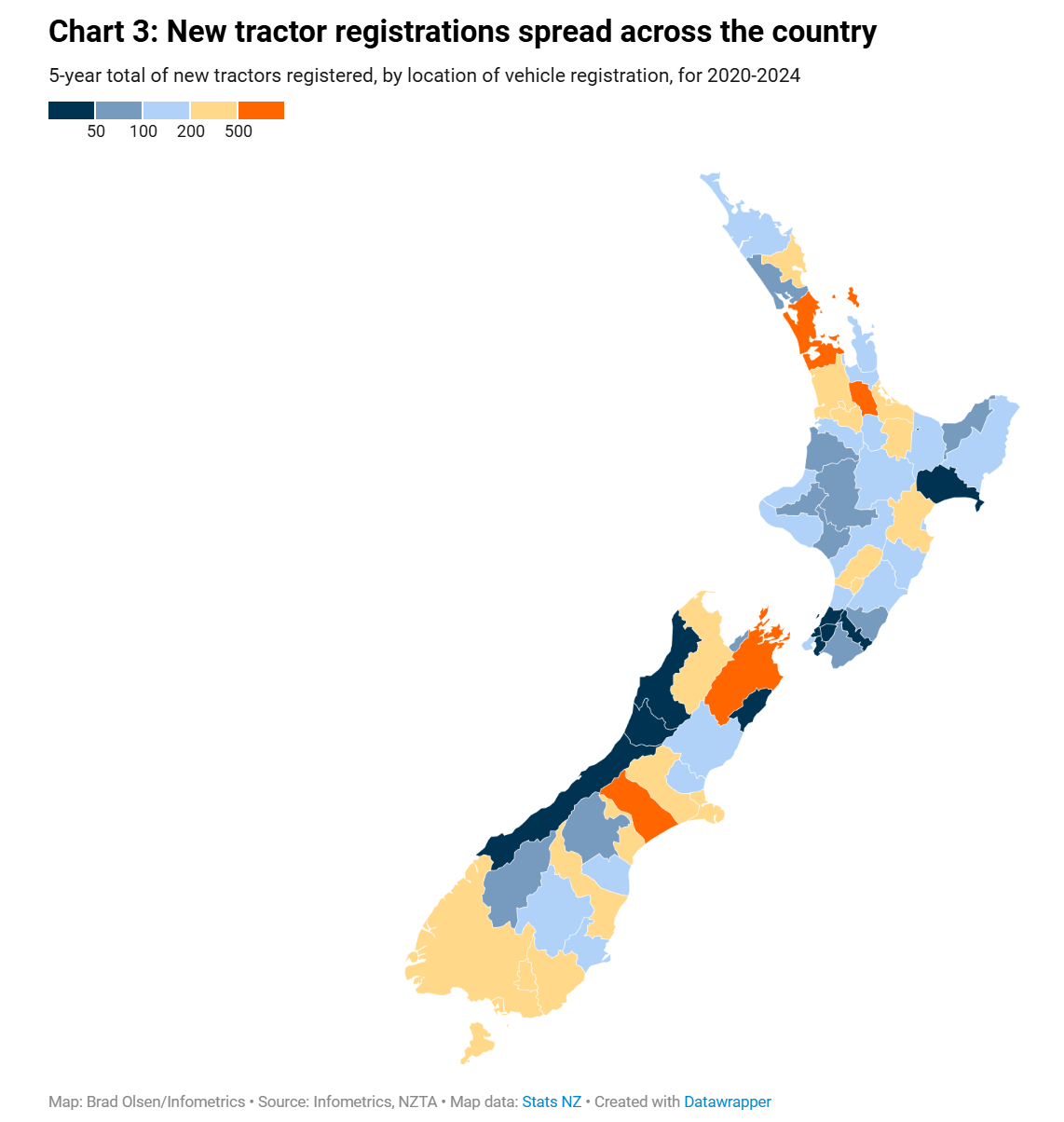

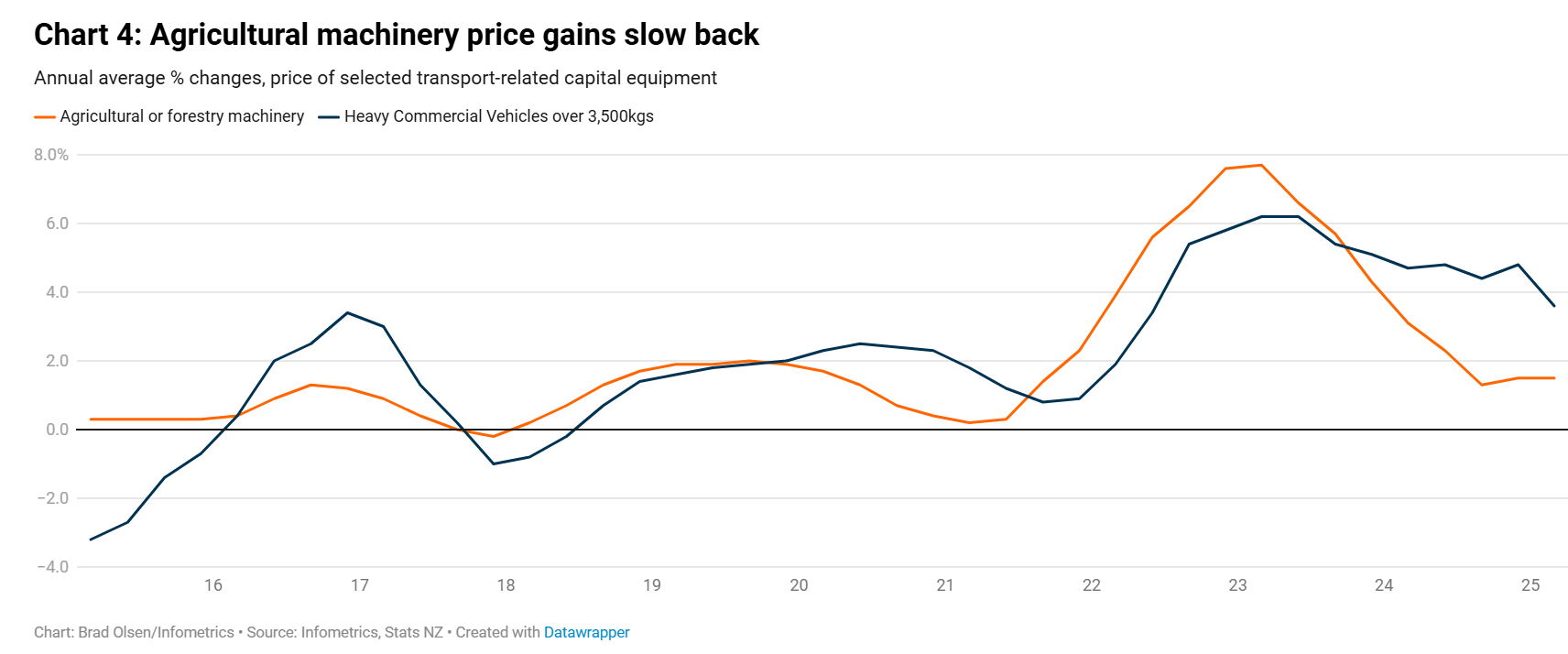

By Brad Olsen* Tractors are often seen as a key piece of farm equipment, and long have been thought of as a good economic indicator of farm spending and investment. Despite the continued focus on tractors in New Zealand, and how they can act as a bellwether for the primary sector, in reality, things are shifting. Infometrics analysis shows that New Zealand passed peak tractor back in 2022, and they are likely become a less important indicator of primary sector activity as the sector shifts to different and more varied technology. Tractor numbers have dropped the last three years Infometrics analysis of Stats NZ and NZTA data shows that New Zealand passed Peak Tractor in 2022, and that overall tractor numbers have been trending down. In March 2022, a total of 34,549 tractors were active and registered in New Zealand. By March 2025, this figure had dropped back to 33,044, a 4.4% drop. Both the actual number of registered tractors, and the 12-month moving average, have now fallen below 33,000, the first time tractor numbers have been beneath this threshold since 2017. Falling tractor numbers are a significant change in trend, although growth has clearly been slowing. The total number of tractors registered in New Zealand had increased substantially over the first five years of the new Millennium, with an annual average increase of 5.5% over the five years to the end of 2005. Tractor numbers grew slower but more consistently after that, up 1.7%pa on average over the five years to 2010, 1.5%pa on average over the five years to 2015, and 1.3%pa on average over the five years to 2020. Then, since 2022, tractor numbers have been declining. Falling new registrations contribute to the decline The decline in tractor numbers is apparent in the low number of new tractor registrations over time. Over the 12 months to April 2025, there were 1,925 new tractors registered in New Zealand, down 17%pa from a year ago and the smallest annual total since mid-2001! The fall in new registrations – and the outright drop in tractor numbers – is likely driven by a number of trends. Some of the downturn will likely relate to more challenging primary sector setting in recent years, with large increases in on-farm costs, in particular fuel, fertiliser, and finance costs. Higher interest rates, plus higher operating costs, will have squeezed revenue and the potential for investment. Assets like tractors may have been run longer than usual, to eek out as much value from the capital expended as possible. A level of continued concertation in farms across the country into larger farm operations may have also contributed to a rationalisation of tractor assets nationally. A smaller number of farms, operating at a larger scale, may be able to operate with fewer tractors overall, with enough tractors for the smaller number of farms around. Increasingly, some farm operations may also have shifted towards more of a contractor model, where farmers have (say) a primary tractor they use, but then for larger operations they now outsource and contract out work to operators with their own tractors. Contractors with their own tractors would lower total tractor numbers over time, as there wouldn’t need to be as many tractors available on each farm being underutilised. Instead, contractors would have a more limited number of tractors, but they would be utilised more often, by moving from farm-to-farm depending on where work is. Tractors could also be getting larger, or more effective or efficient. In that case, farmers would need fewer tractors overall, as a bigger or more efficient or effective tractor could do the work that was previously done by more than one tractor. New tractors spread across the country Although tractors are clearly agricultural in nature and use, where new tractors have been registered isn’t as easy to pick as people might expect. Part of the more unusual pattern of tractor registration is likely to be that tractors are registered in one area to a business or entity, but used elsewhere. That’s particularly likely for Auckland, which had the largest proportion of new tractor registrations over the five years to the end of 2024, with 9.6% of the national total. Key agricultural centres appear next on the Top Tractor list, although it’s still a variety of places. Ashburton come out in second place, with 5.5% of new tractor registrations, followed by Matamata-Piako District (4.4%). Marlborough is fourth, at 4.2%, then Southland District with 3.7%. he North Island had 60% of new tractor registrations over the five years to the end of 2024, with the South Island taking the 40% balance. If the price is right! Limited supply of machinery during the COVID-19 pandemic saw prices for vehicles and transport equipment rise considerably, with annual average agricultural equipment capital costs increasing 7.7%pa at their peak in early 2023. That rise was faster than the 6.2%pa annual average increase seen for heavy commercial vehicles at the same time. However, lower and falling demand for agricultural equipment has seen price increases slow back to 1.5%pa on average over the 12 months to March 2025, and price increases for agricultural equipment in recent times have been the slowest since 2018 (excluding the slowdown over the 2020 pandemic period). These lower price increases, coupled with lower interest rates and enhanced investment settings through the government’s Investment Boost scheme, could support a levelling out in tractor registration numbers. However, given the general and ongoing decline in total tractor numbers, we expect it’s unlikely that tractor numbers increase to any material degree. Tricky to pick the next “Tractor Index” With New Zealand having passed Peak Tractor a few years ago, tractor numbers appear to be an increasingly poor indicator of economic performance or investment into the primary sector. Having constructed and then swiftly deconstructed a Tractor Index makes us wonder, what product or investment would be best to track next to give a simple if imperfect indication of the state of primary sector spending and investment? Technology is an increasingly key focus for the primary sector, and likely making up an increasingly larger share of spending and investment. From drone to Internet of Things (IoT) devices that save time and enhance outcomes, investment in the primary sector is likely less concentrated than before. Wearables are no longer just about smart watches, they’re about tracking and managing feed, pasture cover, and fencing.

*Brad Olsen is the Chief Executive and Principal Economist at Infometrics. This article first ran here and is used with permission.

7 Comments

Or the nation’s tractor fleet being rundown because of tough times of recent years ?

This graph will be repeated many times, from here on in.

Perhaps the decline in new tractor numbers simply reflects the decline in dairy conversions.

Is tractor registration numbers really ever been a good indicator? I have driven many tractors on many different farms over the years and aren't certain of the last time I drove a registered one.

I have a little old David Brown 880 that belonged to my parents, bought September 1969, last registered in 1985. That may be the last time I drove a registered tractor.

Auckland new tractor registrations not surprising. Councils and their contractors (including road construction) seem to have new gear and not for agricultural use.

Tried to come up with an answer to the question about an agricultural bellwether however with farming so diverse now hard to think of anything we buy or use in common.

Perhaps the price of beach front houses?

That's right Wilco, around the Auckland area not only is it Councils etc but many business people have small farms and they buy heaps of new gear even though they don't really need it.

Around our area, Whanganui, most hold on to and maintain older machinery. Looking at the map it is no surprise that the arable areas are still buying new. The reality is NZ has very little arable land so our tractor requirement should be small.

The constant essential workhorse during my farming has been ATV/SxS. Really they took over the job the 880 I mentioned above used to do as a utility vehicle, while making a heap less mess.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.