By Tobias Adrian, Marcello Miccoli, and Nobuyasu Sugimoto

Despite having a market capitalization of about 10 percent of Bitcoin, stablecoins are growing in influence because of the interconnections with mainstream financial markets that stem both from their structure and potential use cases. Indeed, their use and value has surged over the last two years.

Stablecoins have great potential to make international payments faster and cheaper for people and companies. But this promise comes with risks of currency substitution and countries losing control over capital flows, among others. Turning stablecoins into a force for good in the global financial system will require concerted actions by policymakers, at both the domestic and international levels. A new IMF report details the opportunities, risks, and implications.

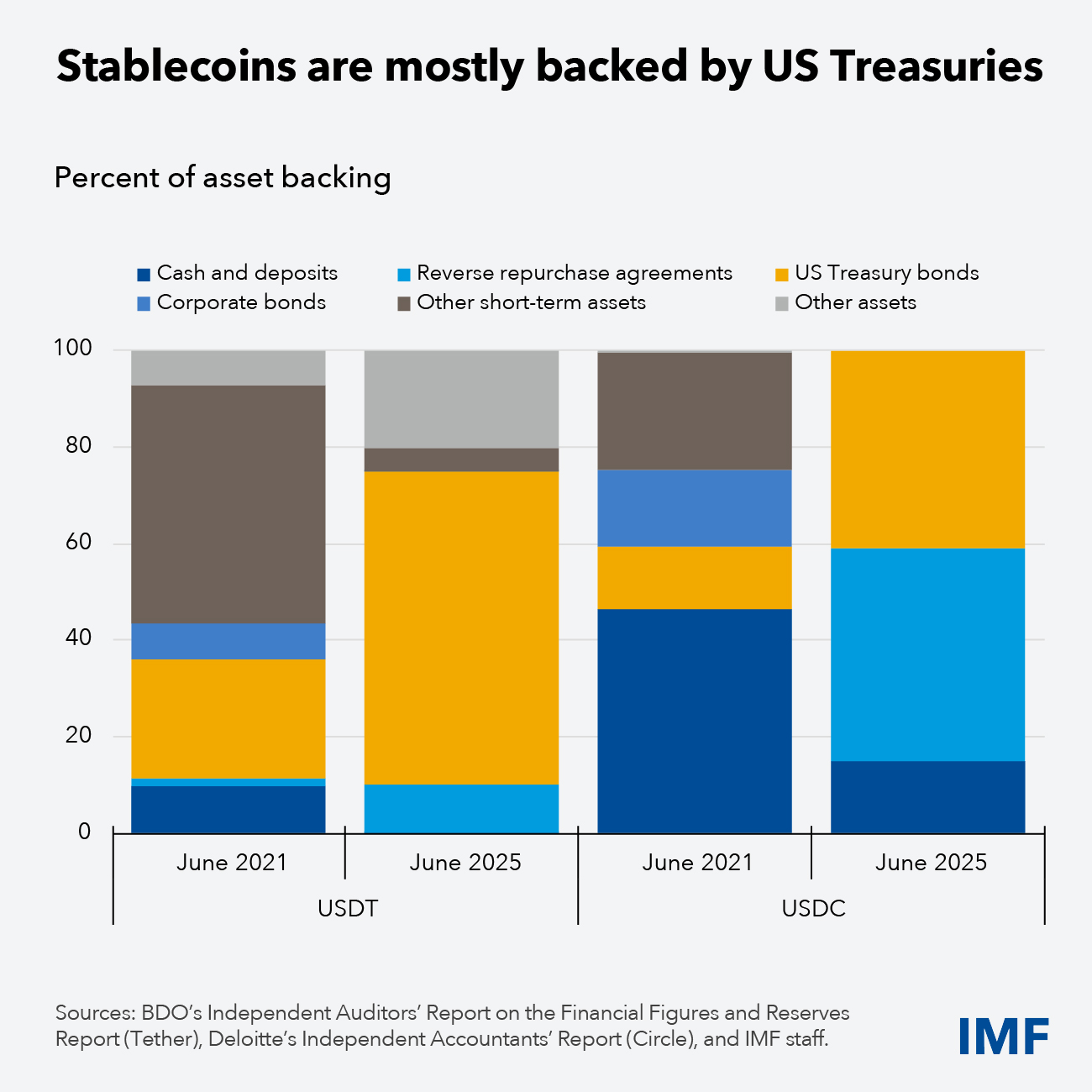

Stablecoins are designed to avoid the wild price swings of native crypto assets like Bitcoin. While both are based on distributed ledgers, the main difference is that stablecoins are centralized (meaning they are run by a specific company) and are mostly backed by conventional and liquid financial assets, like cash or government securities. Most stablecoins are denominated in US dollars and are typically backed by US Treasury bonds.

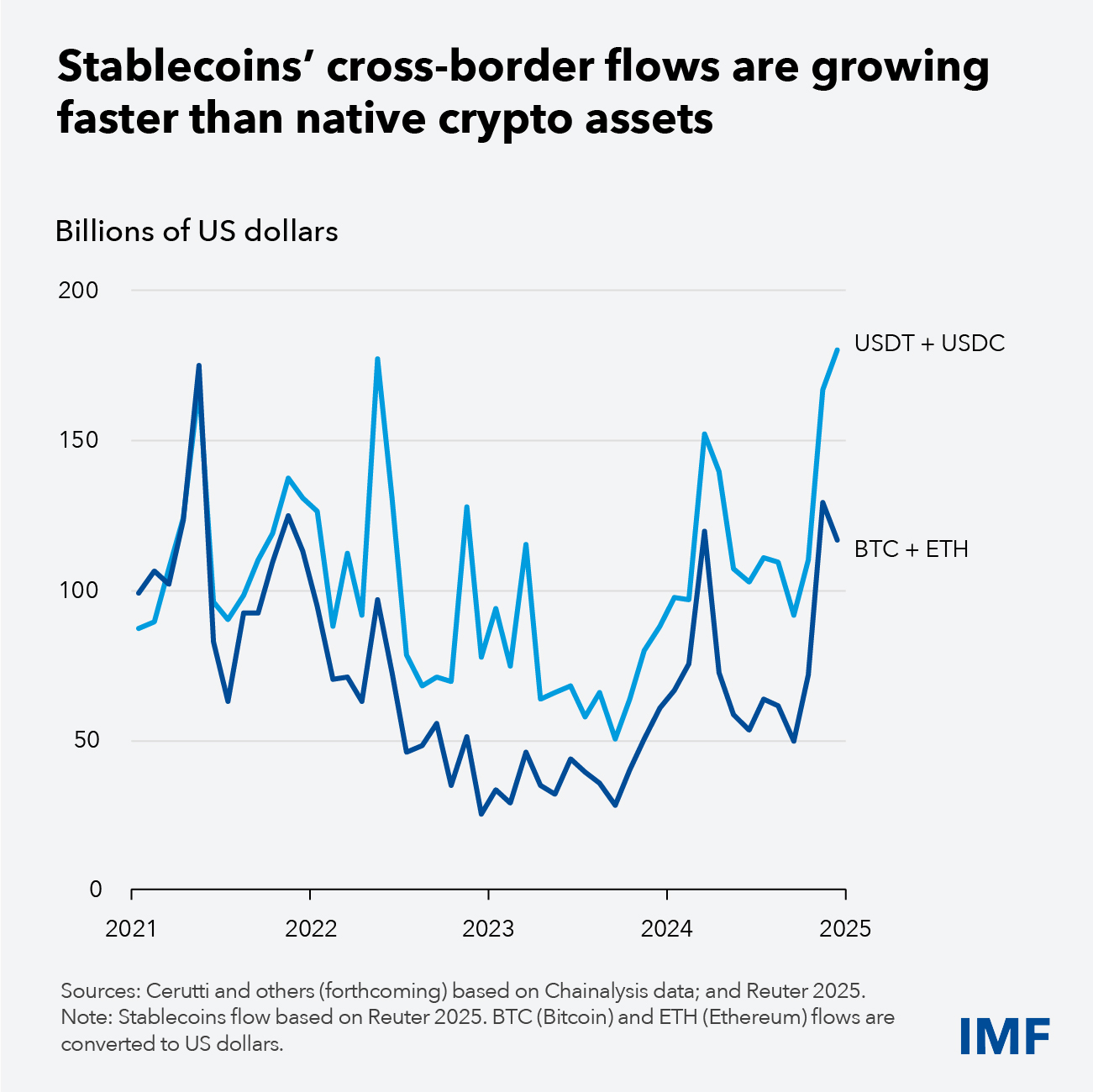

The market capitalization of the two largest stablecoins has tripled since 2023, reaching a combined $260 billion. Trading volume has increased 90 percent, amounting to $23 trillion in 2024. Asia leads with the highest volume of stablecoin activity, exceeding North America. Relative to gross domestic product, though, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America stand out. Most of the flow is from North America to other regions.

Use cases

Today, most stablecoin turnover relates to trading native crypto assets, as they are used for settlement in traditional currencies. However, stablecoins' cross border flows are growing fast.

Stablecoins could enable faster and cheaper payments, particularly across borders and for remittances, where traditional systems are often slow and costly. International payments mostly travel through networks of commercial banks that have accounts with each other, known as correspondent banking. The use of multiple data formats, long process chains, and payment systems with different operating hours results in high costs, delays and less transparency. Some remittances can cost up to 20 percent of the amount being sent. Being a single source of information, blockchains can greatly simplify the processes linked with cross-border payments and reduce costs.

Expanding financial access is another promising area. Stablecoins could drive innovation by increasing competition with established payment service providers, making retail digital payments more accessible to underserved customers. They could facilitate digital payments in areas where it is costly or not profitable for banks to serve customers. Many developing countries are already leapfrogging traditional banking with the expansion of mobile phones and different forms of digital and tokenized money. Competition with established providers could lead to lower costs and more product diversity, leveraging synergies between digital payments and other digital services.

Global risks

Despite their potential, stablecoins do carry risks. Their value can fluctuate if the underlying assets lose value or if users lose confidence in the ability to cash out. This could lead to sharp declines and even runs, triggering fire sales of the reserve assets and disrupting financial markets.

Another risk is currency substitution, when people and companies in a country forego their own national currency, due to instability or high inflation, in favor of a foreign one, most commonly US dollars or euros. This dynamic is still limited today by the need of physical cash in circulation and the fact that national governments have ways to limit access to foreign currency. Being digital and transnational, stablecoins can accelerate the process. While currency substitution could be a rational response by people and companies to an unstable national currency, it decreases a country’s central bank ability to control its monetary policy and serve as lender of last resort.

The same capacity to reduce cross-border frictions could significantly reshape capital flow and exchange rate dynamics. Stablecoins could be used to circumvent capital flow management measures, which rely on established financial intermediaries. Both dynamics are particularly sensitive for emerging markets, which are in principle more vulnerable to volatility emanating from the larger economies.

Stablecoins could also be exploited for illicit purposes like money laundering and terrorist financing, due to their pseudonymity, low transaction costs, and cross-border ease. Without proper safeguards, the use of stablecoins can undermine financial integrity.

International perspective

The implications for the broad international monetary system are also far-reaching, both as a new means of payment and as a disruptor of the existing architecture. The potential for making payments faster and cheaper could be undermined if there is a proliferation of stablecoins that lack interoperability, with various networks unable to connect with each other or restricted by different regulations and other hurdles.

Stablecoin regulation is in its infancy, so the ability to mitigate these risks remains uneven across countries. The IMF and the Financial Stability Board have issued recommendations to safeguard against currency substitution, maintain capital flow controls, address fiscal risks, ensure clear legal treatment and robust regulation, implement financial integrity standards, and strengthen global cooperation.

Established international standards are helping to guide the regulation process, and in fact, according to a recent Financial Stability Board report, “regulatory efforts are increasingly converging toward treating stablecoins as payment instruments.” However, major jurisdictions are taking different stances in key areas. Some risks are being mitigated, but differing approaches create arbitraging opportunities, where issuers could exploit gaps between jurisdictions and locate their stablecoins where oversight is weaker. Some jurisdictions are also considering access to central bank liquidity for certain stablecoin providers, complementing regulatory approaches, and mitigating run risks.

Stablecoins’ cross-border nature adds complexity to the task of managing volatile capital flows and payment fragmentation. The lack of visibility on location and nationality of holders affects the quality of external sector, monetary, and financial statistics. Moreover, stablecoins can be transacted outside regulated entities, hampering monitoring of cross-border flows and effective responses in the event of crises. All this underscores the need for strong international cooperation to mitigate macrofinancial and spillover risks. The IMF is working with international partners on closing these data gaps in the context of Group of Twenty initiatives, and with the Financial Stability Board and other standard-setting bodies on a comprehensive and globally coordinated regulatory approach.

Tokenization and stablecoins are here to stay. But their future adoption and the outlook for this technology are still mostly unknown. Even industry leaders compare the current development stage to the early days of the internet. It is conceivable that a few providers become global dominant players. Commercial banks are also active, issuing their own stablecoins and partnering with central banks to investigate how to incorporate the technology into their systems.

Enhancing cross-border payments also goes through improving traditional infrastructure, and building links between existing fast payments systems, to provide faster, cheaper and more accessible payments. Improving the existing global financial infrastructure might be easier than replacing it. Achieving the best possible balance will require close cooperation among policymakers, regulators, and the private sector.

Tobias Adrian leads the IMF's work on financial sector surveillance. This article was originally posted here.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.