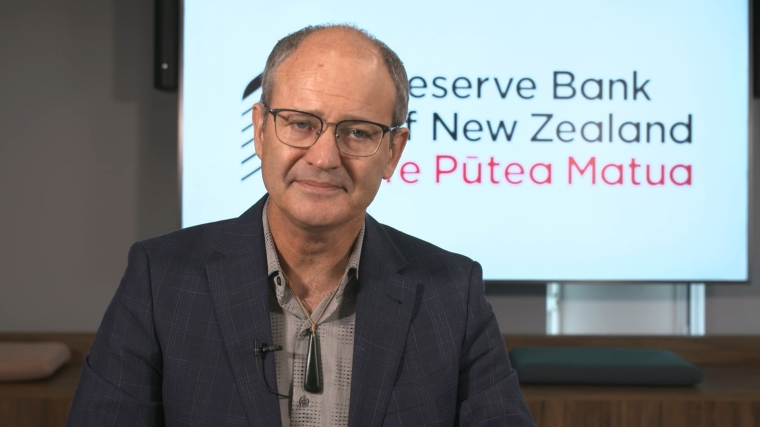

Reserve Bank (RBNZ) chief economist Paul Conway says the central bank still sees scope to cut interest rates, with tariffs posing mostly downside risks to the economy and June inflation coming in as expected.

In a speech to Wellington business leaders, Conway said the bank’s research suggested the US-initiated tariffs would ultimately weaken the New Zealand economy and ease inflation pressures.

“We see tariffs and rising global uncertainty as a negative global demand shock. Yes, it's true that tariffs are disrupting supply chains and may lift costs in some parts of the world, particularly the US, but for us here, the biggest story is about weaker global growth and softer export demand and uncertainty,” he said.

“It's weighing on investment and household spending, so that means a slower growing economy over the middle part of this year, the economy is still in recovery mode, but the recovery is being held back by uncertainty, and you put all that together, it also means slightly less inflation pressures over the medium term compared to what we were thinking previously.”

Conway said this view was already baked into the projections published in the May Monetary Policy Statement. However, at least one member of the Monetary Policy Committee expressed doubt at the time and voted to hold the Official Cash Rate at 3.5%.

Some members felt holding the rate could help “guard against the risk of higher-than-expected inflation from the supply side effects of increased tariffs,” the May record shows.

Those lingering doubts now appear settled, with the chief economist clearly stating the MPC sees tariffs as a negative demand shock that will reduce inflation pressures.

The May statement also sketched alternative scenarios, including one where tariffs drove inflation and forced rate hikes, and another where a larger-than-expected global demand shock could push the OCR down to 2.55%.

But Conway said the analysis in his speech was reflected in the central projection for the OCR to fall to 2.85%, as it had already assumed tariffs would be somewhat negative for inflation.

“That alternative scenario was [asking], what if this is a bit more extreme than what we were thinking? But what I've said today is very much consistent with … the OCR going a little bit further south from where it is currently.”

‘Wait and see’ worse than tariffs

The direct effect of tariffs imposed at the United States’ border would likely be reduced demand for Kiwi exports and lower import prices, he said.

That would mean less export revenue driving economic activity and cheaper imports easing inflation pressure. But Conway said the overall impact may be limited for two reasons.

“First, despite what we like to tell ourselves, we’re not a big exporter for a small country — our export share of GDP is low and has been falling for decades. Second, a large chunk of what we do export is tourism services, which, fortunately for us, are intrinsically difficult to tariff.”

As countries like the United States pull back from global trade, it leaves more room for others to supply more goods or buy at lower prices.

Global supply chains may become less efficient, but most of the added costs would fall on the countries imposing tariffs, with minimal spillover to places like New Zealand.

The biggest drag comes from uncertainty. Conway said the economy was being slowed by a “wait and see” approach among households and businesses.

“When businesses aren’t sure what’s coming, they hold off hiring and delay big investments. Why invest in capital equipment if demand might vanish in a flood of cheap imports? And banks can be just as cautious with lending. Households tend to respond to increased uncertainty by saving more and putting off big spends or job moves,” he said.

“These reactions to uncertainty are entirely logical at the individual level. But they do risk becoming self-reinforcing, with negative effects on aggregate demand in the economy. In fact, uncertainty can end up being more negative for the economy than the thing we are uncertain about in the first place.”

5 Comments

Stay on 6 months y'all!

It's not a very convincing narrative and I wonder if Paul is just saying what he thinks people want to hear - the price of debt is coming down in the near to medium term. That's good for the Ponzi, but Paul doesn't explicitly express that the Ponzi is running on all cylinders, that is inflationary across the economy, not deflationary. I think interest rates are coming down, but not for the reasons that he suggests.

Anyway, there's nothing stopping China from dumping manufactured goods in the Aotearoa / Aussie markets, which would no doubt support deflation. Inventories must be massive. It would be devastating for retailers but that's a trade-off in the relationship. To give him credit, Paul suggests that cheap imports might flood Aotearoa.

The RBNZ is creating uncertainty themselves. The more they fluff around wondering if it's exactly the right time to drop rates and ease credit the worse it gets and the deeper they'll have to cut long term.

They're quite secure in their insecurity. Navigating the ship with their own practice of chicken bone reading.

Nice one Paul, I hope you are applying for the top job

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.