By Raf Manji*

On April 2, 2025, US President Donald Trump announced it was “Liberation Day”. This day would unleash a new era of prosperity, productivity and wealth for the United States. This new era would see a vast swathe of new tariffs on trading partners all over the world, with a focus on countries with large trade surpluses, such as China, Japan and Vietnam.

This unilateral declaration caused mayhem in the financial markets and an outcry from heavily impacted nations. The tariffs outlined seemed random in nature and at odds with the current global trade system underpinned by the World Trade Organization (WTO). Harking back to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, Trump’s focus was on both raising revenue to fund domestic tax cuts and encouraging a return to domestic manufacturing and production. This announcement marked the start of Trump’s attempt to refashion the global trading system to correct what he perceived as long-standing imbalances. The last time there was such a concerted effort to rebalance the trading system was 40 years ago when the Plaza Accord was signed.

Multilateral Intervention: the Plaza Accord

On Sept. 22, 1985, the finance ministers of the US, Japan, Germany, France and the United Kingdom met at the Plaza Hotel in New York. They agreed to jointly intervene in the currency markets and engineer a depreciation in the value of the US dollar, which was seen as a major cause of a growing US current account deficit. American manufacturers had been vocal in their struggle to export under an overvalued dollar, and this was starting to have a political impact.

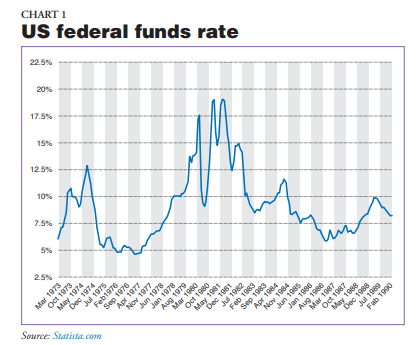

The appreciation of the dollar was a result of very high interest rates through the 1970s as a response to inflationary pressures caused by the fiscal costs of the Vietnam War, the abandonment of the gold peg, and the subsequent oil price shocks following the OPEC oil embargo in 1973 and the Iranian Revolution in 1979 (Chart 1). Prior to the meeting at the Plaza Hotel, the G5 had agreed in January to intervene in the currency market, and further meetings in July and August paved the way for a more formal shift in their desire to see the US dollar depreciate.

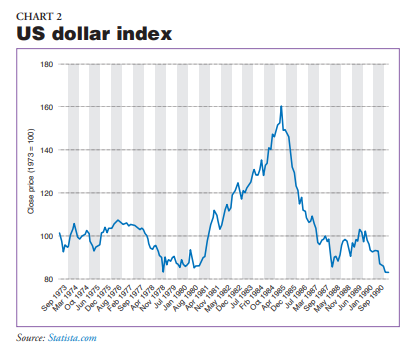

From February 1985, the dollar fell from 260 to 155 yen by September 1986. Against the deutschmark, it fell from 3.40 to 2.00 and the pound appreciated from 1.10 to 1.47. In terms of the intervention, the depreciation of the dollar was substantial and thus the Plaza Accord could be considered a success in that regard. In fact, the move was so sharp that finance ministers were forced to step in and halt the slide in early 1987 with the Louvre Accord (Chart 2). This time, they met in Paris at the Louvre Palace, with Canada included as part of an enlarged G6 grouping (Italy was part of the G7 but did not sign the accord), and agreed to intervene to stabilize the dollar and halt the extreme depreciation.

However, whilst the trade deficit with Europe declined, the impact with Japan was not as noticeable. Much of this was due to the structure of the Japanese domestic market and import rules, leading to ongoing friction between the US and Japan. Even after the Louvre Accord intervention, the yen continued to strengthen, and this caused the Bank of Japan to loosen monetary policy. In turn, this fueled an asset price bubble which burst at the end of the 1980s ushering in a long period of economic stagnation for Japan.

The 1985 Plaza Accord was the first serious financial market intervention by the major economic powers and came at a time when financial markets were experiencing a “big bang” deregulatory moment. The 40th anniversary is a useful time to reflect on both its impact and its genesis.

Imbalances are a fact of life, whether in nature, in business or in ordinary life. Trade has always been predicated on the forces of supply and demand. Any imbalance allows for power dynamics to emerge, and this can lead to stresses in international relations, with tariffs, embargoes and military conflict as a result. We are seeing this now. We have also seen this before.

Monetary Conflict: the American Revolutionary War

Some 250 years ago, the US was victorious in the Revolutionary War with Great Britain. This was a war fought for independence from a colonial power and for self-determination. Underpinning this conflict was an imbalance in trade, taxes and currency. The British government passed three Parliamentary Acts in succession between 1764 and 1765 which attempted to prevent domestic US currency issuance and unfair trade practices. The Currency, Stamp and Sugar Acts essentially sought to place currency restrictions, impose administrative costs and apply a tax, all with the aim to control the US economy and raise revenue to pay off British war debts.

This backfired spectacularly on the British and the subsequent conflict helped establish the US as a sovereign state. It showed the consequences of intervening in the trade and currency markets to exert power and influence, rather than managing an imbalance in trade itself. This strategy, commonly known as mercantilism, had been part of the colonial policy toolbox since the 15th century but the US rejection of the British in the late 18th century tempered this approach somewhat.

However, trade and conflict were never far away. As Germany became more influential in the late 19th century, Britain responded with economic sanctions, blockades and tariffs. Economic nationalism boosted investment in military spending, particularly on naval development. Controlling trade routes and key supplies was a major plank of economic policy. This was a major cause of friction leading up to World War I in 1914.

A New Global Financial System: Bretton Woods

The war and the resulting 1919 Treaty of Versailles postwar settlement left deep scars on the German economy, with the use again of gold-linked currency demands as a major plank of the peace agreement playing a part in the hyperinflation that followed. The next two decades would see a stock market crash, a global economic depression, and another world war. The conclusion of World War II ushered in the first attempt at an organized global financial structure at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference. Global trade and currency were top of the agenda with the debate focused on attempting to create an international trade system with inbuilt stabilizers (Keynes’s Bancor) or a US-dominated system with the dollar pegged to gold as the basis for all global trade. The outcome of the conference was the US dollar becoming the default global currency and providing the US with what French Finance Minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing called an “exorbitant privilege”.

Abandoning the Gold Standard: the Nixon Shock

This privilege continued even after the “Nixon shock” in 1971 when President Richard Nixon allowed the dollar to float freely by abandoning the Gold Peg, which had been in place since Bretton Woods. The cost of the Vietnam War and depleting gold reserves forced Nixon’s hand. The unilateral move caused major problems for many countries that were linked in the dollar, particularly oil producers. Nixon also imposed a short-term 10% import tariff to try and soften the impact of exchange rate movements, as well as wage controls.

This move caused an immediate depreciation of the dollar with major consequences for key trading partners and oil producers. The BOJ intervened in the currency markets to support the dollar-yen rate at 360 but to no avail, as the dollar fell to 300 by early 1972. Attempts to create a new fixed exchange rate system through the Smithsonian Agreement in late 1971 had not worked and by 1973 a full floating exchange rate system was in place.

There were further consequential impacts which included pressure on oil producers who experienced a loss in revenue due to oil being priced in dollars. The US support for Israel following the Yom Kippur war in October 1973 saw an oil embargo imposed by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries, causing a major spike in the oil price. The Iranian Revolution in 1979 placed further pressure on oil supplies, seeing the oil price go from $3.50 a barrel in 1971 to $38 by the end of the decade.

The resulting inflation and stiff hikes in US interest rates capped off a turbulent 1970s leaving the US heavily overvalued as global markets expanded and the US economy came out of the doldrums. The resulting strong dollar provoked concern from major trading partners, sparking conversations at the G7 summits at the Versailles Summit in 1982 and Williamsburg in 1983 which would pave the way for the meeting at the Plaza Hotel in 1985.

The need to step back into the markets with the Louvre Accord showed how challenging it was to manage a floating currency system as global trade increased, and financial markets became more complex. Included in the Louvre Accord were a range of other monetary and fiscal shifts, acknowledging that currency intervention alone could not fix imbalances in the financial system.

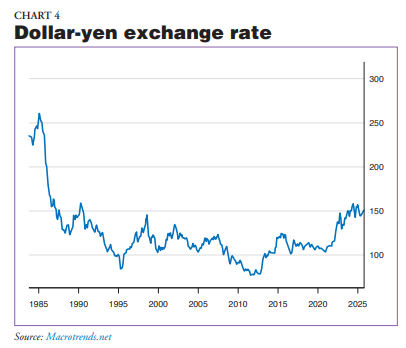

These measures did not immediately help, as the dollar continued its fall against the yen, hitting 125 in April 1988 before rebounding to 160 in April 1990 as US interest rates rose and the Nikkei crashed. Two years later the dollar-yen rate was back down at 125. It might have seemed then that trying to fix exchange rates was a fool’s errand and that a better policy would be to intervene only when markets became stretched or overly volatile.

Global Capital: Hot Money, Fiery Markets

However, this did not stop authorities attempting to create a European-wide currency system with individual currencies floating within agreed bands. A European Monetary System had been in place since 1979, with member countries agreeing fluctuation bands for their currencies within the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). In 1988 work began on advancing the case for European Monetary Union with a future European currency overseen by a European Central Bank.

The UK had not initially been part of the ERM but joined in late 1990. Two years later it would be forced out in a humiliating manner, with the pound unable to hold within its prescribed band. Poor economic conditions, high inflation, large deficits, and the depreciating dollar had delivered an exchange rate that was simply too high for the UK economy to bear. The UK was forced into leaving the ERM and allowing the pound to float, in this case depreciating swiftly. The pound fell against the dollar from 2.00 to 1.50 and remained in a range of 1.40 to 1.70 for the next 10 years.

Black Wednesday, as the exit became known, was the latest example of a fixed currency regime not working due to many other factors which were too complex to manage. The Bank of England intervened heavily to support the pound as it was required to by the ERM but eventually gave up as the speculative selling pressure and economic fundamentals made it futile to continue. The 1990s saw further financial crises as currencies experienced rapid and extreme shifts due to speculation and economic fundamentals shifting.

Yen strength continued to plague the Japanese economy. The endaka (high/strengthening yen) which had started with the Plaza Accord, saw the dollar-yen rate fall below 100 and by 1995 it had reached 80. Much of this was due to dollar issues, with a burgeoning US budget and trade deficit, as well as a Mexican economic crisis. This placed huge pressure on the Japanese economy, which was still reeling following the Nikkei crash due to a still heavily indebted banking system. Concerted currency intervention from the major central banks did take place with the dollar rising to 100 yen by the end of 1995.

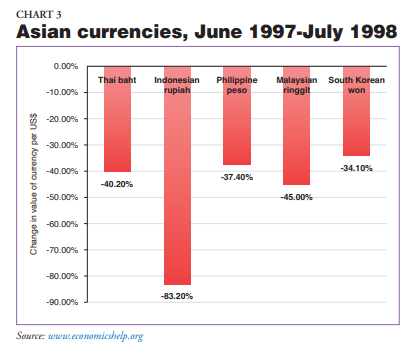

Unfortunately, for monetary authorities, there was no stability to be found. No sooner was one crisis averted than another appeared. The Asian Financial Crisis was one such example. It started in 1997 in Thailand with the collapse in the value of the Thai baht due to capital flight. A fixed peg to the dollar backfired when speculative capital flows into fast growing Asian economies started to unwind as real estate bubbles burst, exports became uncompetitive, and economic growth slowed. This volatile cocktail caused a rush for the door as risk magnified. As with the UK’s ERM crisis, the initial response of hiking interest rates did not work; eventually many Asian currencies collapsed (Chart 3).

Currency & Banking Crisis: the IMF Steps In

Unlike the Plaza Accord, which involved the world’s major trading partners, the international response to Asian Financial Crisis was through the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The response was in the form of Structural Adjustment Programs which incorporated debt restructuring, fiscal reform and new banking regulations, including bankruptcy procedures. This was a very painful process for the countries involved, particularly Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines and South Korea.

As well as economic and financial impacts, there was political turbulence with Indonesian President Suharto forced to resign after widespread rioting, and in the Philippines, President Joseph Estrada was eventually ousted. One outlier in the crisis was Malaysia, which responded by imposing capital controls rather than accept financial medicine from the IMF. This worked to reduce speculative forces and was a signal to the market that hot money was not welcome. The squeeze on speculative capital flows enabled Malaysia to restructure heavily indebted banks and corporates in a more orderly fashion and stabilize the economy without IMF intervention.

The role of the IMF would come under scrutiny as the effects of the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) spilled over into Latin America and Russia and saw the collapse of one of the world’s preeminent hedge funds, Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). The IMF had encouraged emerging economies to open and liberalize their capital account, which led to large inflows of new funding, highly leveraged debt structures and overvalued currencies. As these flows reversed, suddenly the contagion effect from Asia spread globally with huge capital outflows from Latin American countries, followed by a Russian sovereign debt default in August 1998.

The collapse of LCTM a month later capped off a torrid time for global markets. The fund, which included the Nobel Prize winners Myron Scholes and Robert C. Merton on its board, was regarded as the smartest hedge fund in the world. Their ability to arbitrage and leverage enabled very high annual returns. However, the rolling impacts of the global deleveraging caused a rupture in their positions, and with liquidity at a premium, their positions crumbled. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York stepped in to organize a $3.6 billion bailout, underwritten by major financial institutions. This enabled an orderly unwinding of positions and an avoidance of wider market panic.

Added to this turmoil was another round of currency intervention. Having traded at 80 to the dollar in 1995, the yen had now weakened to 148 during the crisis. Once again, there was concerted intervention, resulting in a sharp move back down to 115. It would end the decade at 105, a long way from its pre-Plaza Accord rate of 260.

The 1990s was a decade of market liberalization, in both trade and capital flows. The European Union project was advancing, Germany had reunified, and the USSR had dissolved. Emerging markets grew strongly as global trade increased, and capital flowed into new opportunities. China and India were both advancing out of old postwar economic structures and setting the scene for the 21st century. All these shifts had brought increased prosperity but also turbulence and volatility as new capital flows, often highly leveraged, disturbed a more traditional trading system. This made global financial management a challenging undertaking with new financial market products always a step ahead of bank regulators and treasury officials.

The New Millenium: Exuberance & Hubris

As the new millennium was celebrated with some relief that the Y2K changeover had not caused a major meltdown, the next crisis was not far away. This time it was the “irrational exuberance” of the US stock market with new technology stocks drawing in capital, and a bubble that mirrored the Japanese experience of the late 1980s. A mixture of hot money, rising interest rates and frothy valuations saw the US Nasdaq index crash almost 80% from its highs. Pressure on the Japanese economy had seen the BOJ intervene aggressively to prevent the yen falling below 100 to the dollar. The Plaza model of concerted currency intervention had now become common monetary policy.

This model would be tested further and expanded as the markets reacted to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, when further pressure saw the BOJ and other central banks intervene. The dollar-yen rate would hold above 105 until the aptly named Global Financial Crisis (GFC) threatened to unravel the global financial system in 2008. The GFC once again saw a coordinated response from global central banks. As this was primarily a US banking crisis, the response was led by the Fed and included a wider range of interventions, including credit and currency swap lines, systemic bank bailouts and sovereign and corporate debt purchases.

The Fed was eventually able to stabilize markets with forced buyouts, recapitalizations and bank failures. This time Asian economies were not so heavily impacted due to policy shifts post AFC and a less leveraged financial system. However, Europe did not fare so well, and the mismatch between a joint European currency, the euro, and individual country fiscal policies made recovery challenging. Currency shifts benefited some countries more than others, and this lack of internal coordination left European countries unable to take appropriate individual action. This led to a rolling crisis within the EU, with Ireland, Portugal, Greece and Cyprus all facing serious financial problems.

At the root of many of the post-Plaza Accord financial dislocations was the issue of ongoing imbalance in trade, which was exacerbated by the flow of speculative and highly leveraged capital. Over time the capital account would become more influential on currency rates, and this would often leave currencies unable to adjust to trade imbalances. One example of this was the reaction to the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011. The US recession and the earthquake fueled expectations that there would be a mass repatriation of yen to support the disaster response and support the stock market which was badly shaken. The yen rose to 76, an historic high against the dollar, before major intervention to drive the dollar back up. It eventually recovered as selling pressure retreated and calm was restored.

Stability Reigns but New Challenges Appear

By 2015, 30 years after the Plaza Accord, markets settled down for a short crisis-free period. This included the first Trump presidency in the US and the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. But growing corporate debt placed pressure on global economies and by the time Covid-19 arrived, markets were already feeling the pressure. As the virus started to spread and lockdowns began to be implemented, markets panicked and saw the biggest fall since the 1987 crash. They fell some 20% to 30% in a short period, triggering a wider shock than even the GFC. Authorities responded with major monetary and fiscal packages, providing both liquidity, fiscal stimulation and direct financial transfers. Although markets recovered quickly, there was a deep scarring in the economy with many businesses struggling to recover from the shutdown.

With interest rates at record low levels, and negative in some places, as markets recovered, capital shifted to assets, driving stock and property prices higher. The dollar strengthened as both demand for dollars alongside stimulus and supply chain pressure saw inflation take hold. The yen now started to move towards 140 in June 2022. The Japanese government and BOJ both made statements expressing concern at the weakening yen. Having spent most of the last 20 years trying to deal with yen strength, the concern was now the opposite. The yen moved to 160 in 2024, resulting in intervention alongside a small hike in interest rates to stabilize the yen’s depreciation (Chart 4).

At the time of writing (October 2025), the dollar-yen rate is at 150 and JGB yields are at 1.7% for 10 years (the highest level since the GFC) and 3.3% for 30 years. The yen is at its weakest level since the 1980s and bond yields are at their highest. Something is out of balance here.

Tariffs, Currencies & Bonds: the Trump Shock

The last six months have seen unilateral action from Trump, with tariffs as the main policy tool to rebalance the US trade account, alongside requests for investment in the US in the form of new manufacturing and military spending. This unilateral approach, or “Trump Shock”, has parallels with the Nixon Shock in 1971. It is a major shift away from the last 40 years of coordinated intervention to manage and deal with trade imbalances, financial turbulence and market dislocation. This has seen the G7 sidelined as the key organization for managing global financial policy. This “America First” approach has seen other groupings start to talk more about economic matters, including the BRICS grouping and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) where China has more influence.

However, although China and other growing economies like India, Brazil and Indonesia are engaging more in the international sphere, the US dollar remains supreme as the international medium of exchange and store of value. Currently, Asian countries hold around $7 trillion in reserves. The question now is whether there will be some multilateral agreement to manage global imbalances or whether Trump will continue to push forward with his own agenda. So far it seems like the latter.

This agenda was laid out in a paper by Stephen Miran, a former US Treasury advisor and investment strategist. Titled “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System,” it outlines a three-pronged approach to deal with “the persistent overvaluation of the dollar”. The policy tools to deal with the overvaluation involve tariffs, currency and bonds. This is not dissimilar to both the 1971 abandonment of the Gold Peg, and both the Plaza and Louvre Accords. But the approach is unilateral in nature and contradicts the global policy framework built up since 1985.

In the paper, Miran proposes the use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) from 1977 to enable Trump to make unilateral decisions, which include not just tariffs but also charges for currency use and potential bond restructuring. This approach of “Tariffs then Dollars or Investment” seemed more of a blue sky think-piece than actual policy plan but so far this plan seems to be Trump’s international economic blueprint for the US. Reinforcing this shift is Trump’s negative posture against current Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, and an attempt to remove a sitting Fed board member, Lisa Cook. On Sept. 15, Miran was appointed to the Fed board to fill a temporary vacancy until January 2026.

As Trump continues to expand his control of all economic policy levers, two possible scenarios loom. Will we see a return to a 1985 Plaza-style accord to manage the current global imbalances or will we see a 1971 Nixon Shock-style approach in the form of a Mar-aLago Accord? Current events point to a Trump Shock, with the US, as it did in 1944 and 1971, taking a unilateral approach to restructuring the global trading system.

Bretton Woods 2: the Ghost of Keynes

John Maynard Keynes had argued strongly at Bretton Woods for a new system that enabled balanced trade, with automatic stabilizers in place should trade imbalances become too extreme. This was like a currency system floating within pre-determined bands, such as the ERM. As with the UK experience in the ERM, sometimes the broader requirements of a multilateral system can create headaches at the individual country level. This speaks to the conflict between domestic and international drivers, with domestic populations not always sold on the benefits of increased trade and strict fiscal boundaries.

The US view prevailed at Bretton Woods with the dollar underpinning the global financial system as it was then, supporting postwar reconstruction, development and investment. This influence would further be extended with the birth of the Eurodollar and petrodollar markets, all supported by a global military reach. The Nixon Shock saw the US abandon the gold standard but with the dollar remaining as the global currency. As global trade increased into the 1980s, it was clear the US had to deal more cooperatively with its key counterparts, leading to the Plaza Accord intervention.

The following 40 years saw multilateralism and cooperation as the core operating system of the global financial system, notwithstanding the preeminent role of the US. Global central banks, through the G7 initially, the IMF and World Bank all worked together to keep the system afloat through multiple and regular crises. Trump has dismissed this approach, taking the US back to unilateral action and ad hoc groupings and relationships that are driven directly by US interests.

If this approach continues, then we can expect to see a more transactional approach to the US currency system and a possible restructuring of US debt. As Miran proposes, this could be in the form of user fees for interest repayments or remittances as well as charges for accessing currency swap lines. As part of a general dollar devaluation, current US debt maturities or coupons could be renegotiated with current debt swapped into longer duration at a lower cost for the US treasury.

This type of policy shift would amount to a full and unilateral restructuring of the global trading system, not seen since Bretton Woods or the Nixon Shock. As Miran notes in his introduction, it has “become increasingly burdensome for the United States to finance the provision of reserve assets and the defense umbrella, as the manufacturing and tradeable sectors bear the brunt of the costs”.

Only time will tell as to whether the tariff shake-up is the beginning of something more substantial, but the current evidence suggests that the 40-year-old multilateral and coordinated approach of major economies is in for a major change. President Trump is serious about the US no longer bearing the burden of costs as the global hegemon. For countries with major holdings of US currency and bonds, this will have serious consequences.

This article is from Economy, Culture & History Japan SPOTLIGHT Bimonthly, and is used with permission. Its title is; Balancing Act: 40 Years on from the Plaza Accord by Raf Maji, and it appears in Japan SPOTLIGHT, issue of Jan./Feb. 2026 (#265). The publisher is the Japan Economic Foundation.

*Raf Manji is an experienced policy professional with a background in global markets, social enterprise, non-profits, and local and central government. He is currently Principal Research Fellow at the Institute of Indo-Pacific Affairs.

2 Comments

Rome, too, found the increasing entropy too much to bear.

But apparently, we don't learn too good.

The difference is that the Roman Empire was local, and mostly solar energised. The current system is global, and done one the basis of mined energy. Which is decreasing in energy return. Even as maintenance demand escalates.

There will be a reconciliation between forwards bets and remaining planet. The question is: who will hold valid proxy? If anyone...

This is an interesting read. Thanks Raf.

Good to get some insight and overview of the world's exchange rate and financial crisis history.

It seems the US is happy to have the rest of the world finance its government and international trade deficits but doesn't want to pay the interest cost of its debt. It continues to proceed under the decades-old delusion of cutting taxes and not being able to pay the cost of providing government services and infrastructure.

That delusion is shared by many governments and voters these days including it seems in New Zealand (including the mythical "growth will fix it" mantra).

If international investors accelerate their reluctance to finance US debt and become more concerned about repayment by the capricious Trump regime things may get messy. Or it could be another "TACO" trade.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.