The tide turns slowly when mortgage rates are reduced.

That's arguably why we aren't really seeing too much of a visible pickup in the economy yet. People appear to be pretty cautious and reluctant to get out spending again. Confidence may take time to return.

Some economists, particularly those with banks, are pushing quite aggressively for more and faster interest rate cuts.

But would that help?

Would more aggressive upfront interest rate cuts help the overall economy now, when the cuts that have already been made are probably not yet taking full effect?

A big question for me this year was always going to be just how quickly our economy could recover as interest rates started coming down. It was suggested that since the sharp recession we saw last year was essentially engineered by the Reserve Bank's tightening of monetary policy (through Official Cash Rate hikes) between 2021 and 2023 - that reversing those OCR hikes would see the economy recover more quickly than might 'normally' happen after a recession.

But such thinking probably leaves out the human factor. People lose confidence in the idea of spending and have to be cajoled back into it.

So, our economy is taking time to recover. But I think there are clear signs it is recovering and so it becomes valid to question how much more 'medicine' (through lower-still mortgage rates) the patient needs.

It's worth having a thorough look at where our mortgage rates have been and what's happening with them at the moment in order to understand the dynamics of the whole thing.

So far, the OCR has been cut from the cycle peak of 5.5%, reached in May 2023, to 3.5%, with the next review of it due on May 28.

The banks started reducing our mortgage rates substantially last year even before the RBNZ decided it was sufficiently on top of inflation to start reducing the OCR in August.

Let's have a look at some examples of mortgage rates:

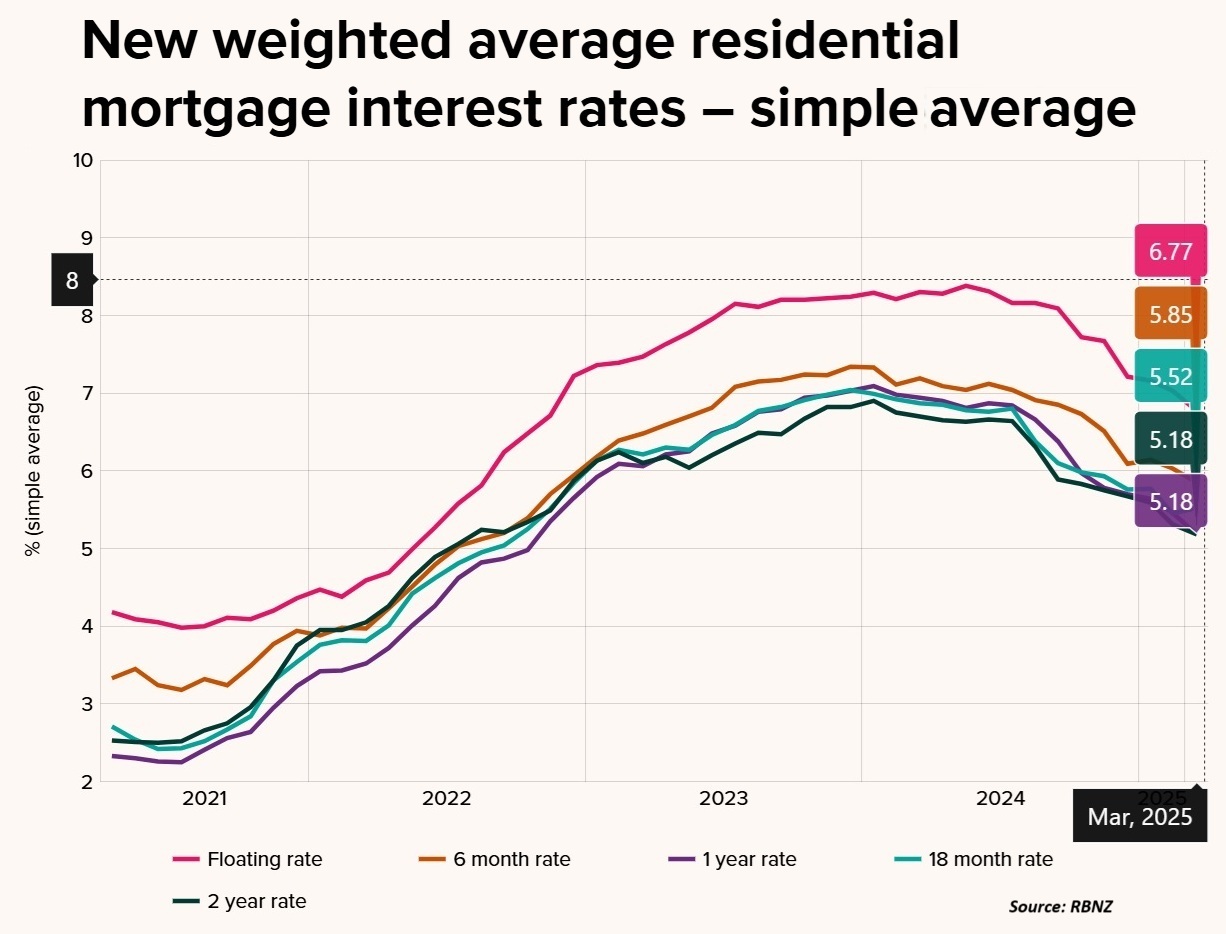

As of March 2025 one-year fixed mortgages became the most popular again among those owner-occupiers taking up new mortgage commitments in March. So, we’ll use one-year rates for example purposes in terms of looking at where rates have been and where they are now.

The RBNZ produces figures that show the weighted average interest rate of new mortgage commitments uplifted each month. So, this is a 'real average' of what's being paid.

The rates have been on quite a journey. The RBNZ figures show us that at the end of the cycle of very low interest rates before inflation went through the roof, the average weighted one-year mortgage rate bottomed out at 2.25% in July 2021.

But as the RBNZ cranked up the OCR in order to combat inflation that peaked at 7.3% in mid-2022, so, mortgage rates were forced higher quickly.

In January 2024 the average one-year weighted mortgage interest rate hit a peak of 7.09%.

However, by December 2024 the weighted one-year average was down to 5.70%.

And by March 2025 the figure, (latest available), was 5.18%.

The current popular advertised one-year rate of course is 4.99%. So good numbers of folk are signing up at that rate.

But that’s new mortgages.

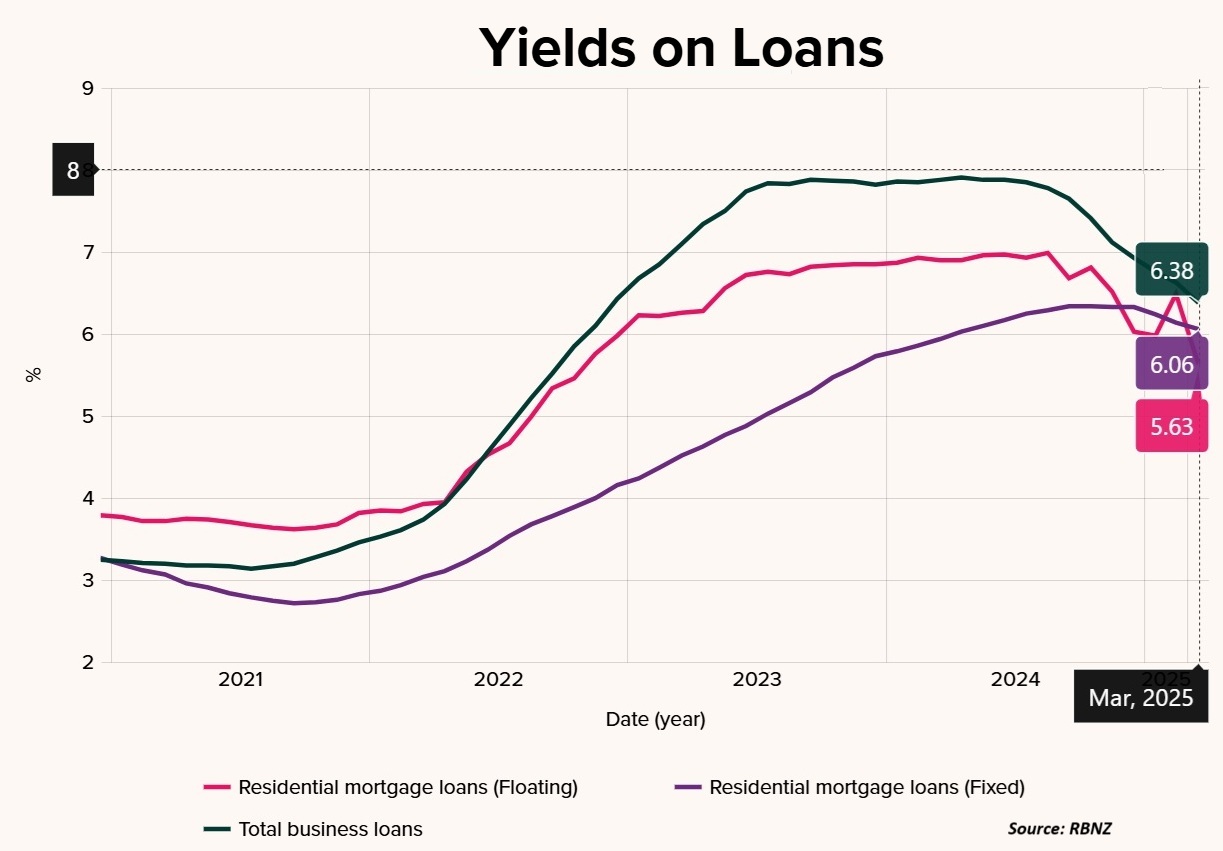

The RBNZ collates the figures on what the banks' yields are on their mortgages to existing customers. And these figures demonstrate the lags we see between when rates are moved and when customers feel the impact of those moves.

These figures show that if we again look back to the pre-inflation surge mortgage rate figures, the low point for the yield across all mortgages was 2.83% in September 2021.

Breaking it down, the low point yield for fixed mortgages was 2.72% in September 2021, while for floating it was 3.62% in the same month.

Because of the lags between when rates were moved and when existing customers reset their rates, the yields for banks on the mortgages were still rising for some time after rates were 'officially' coming down.

In fact, the peak yield across all mortgages was 6.39%. And that wasn't hit till October 2024 - well after interest rates had been coming down. By December the yield across all mortgages was down to 6.29%, so, only a slow descent.

However, by March 2025, which is the latest date we have for figures, the yield was down to 6.00%. Very notably that was down from 6.18% in February - so, we are really starting to see some movement now. The ball is rolling. More and more people are feeling those lower rates.

And it is worth breaking down the figures a little further - to look at the yields on floating rates and the yields on fixed.

The peak yield on floating rates was 6.99% in August 2024. It was 6.03% by December 2024. And it was 5.63% by March 2025.

For fixed rate yields the peak was 6.34% in October 2024 and this one really did come down slowly. In December 2024 it was only down to 6.33%.

However, in March 2025 it was 6.06%, notably down from 6.14% in February and 6.24% in January. So, again things took time to get rolling. But they are rolling now.

And just for fullness of information, we'll throw in the yields on business loans (this doesn't include ones fully secured by residential mortgages). These had a low of 3.14% in July 2021, a high of 7.91% in April 2024 and by March 2025 were down to 6.38%.

How has this all related to what's coming out of people's pockets?

Well, looking broader, and through another RBNZ data series, we can see that the previous cycle-low point of mortgage interest charged by the banks in a quarter was in the September 2021 quarter, with $2.32 billion charged. Scheduled repayments that quarter (this includes both interest and principal repayment) were also at a low of $4.795 billion.

Once rates rose, the peak of interest charged was not actually reached until December 2024, with $5.804 billion interest and $7.666 billion scheduled repayments.

So, in layperson's terms, $2.871 billion more (in a quarter) came out of pockets for scheduled repayments at the peak of the interest rate cycle than there had been during the historic low times of three years earlier. And remember, this peak was as recently as the December quarter. The tide has taken time to turn.

What about the March quarter, 2025?

It's starting to come down

Well, the data shows us that the interest bill had reduced to $5.571 billion, while the scheduled repayments were $7.527 billion. That's a $139 million quarter-on-quarter reduction. So, it's starting to come down - but it's only just started to come down.

As of March 2025 the mortgage loan book of all outstanding mortgages was $373.993 billion.

Within this, some $150.161 billion - just over 40% of the mortgage pile - was, as of March, up for an interest rate reset by the end of September 2025. That's about $25 billion worth of mortgages every month up for a reset, which is a lot.

In addition, $48.33 billion of mortgages was on floating and so could be reset at any time as well. Which means that nearly $200 billion, just over 53% of the total mortgage book, could have an interest rate reset - at lower rates - by September.

Some people have already had a mortgage rate reduction and face lower payments.

A heck of a lot more people are due for that to happen within the next few months.

This will help. People will start to notice more money in the pocket and start to feel more confident.

What about the economy so far?

In terms of key economic data, the annual inflation rate was 2.5% as of the March quarter, tucked into the 1% to 3% range the RBNZ is charged with achieving. Our GDP emerged tentatively in the December quarter (0.7% rise) from the large hole it fell into in the June and September 2024 quarters. This was better than the economists' predictions. Our unemployment rate for the March 2025 quarter remained at 5.1% - better than economists' predictions and indeed the prediction of the RBNZ, which was for a rise to 5.2%. (Economists generally said 5.3%).

The current expectation is that our GDP will have grown again in the March quarter, although nobody's expecting that it's shooting the lights out. But growth is growth. It's a starting point. A very big bright spot in the economy has been dairy and meat exports and I suspect the impact that's having, and will have, on regional New Zealand is not yet being fully factored in by many of the country's economists.

But the point is that the signs of recovery are there. Slow and gradual, yes. But there. Much of the statistical information that's coming out about the economy so far this year has been BETTER than economists, and indeed the RBNZ, have expected.

And a word on the global turmoil? Well, surely we've just got to judge by events as we see them develop rather than trying to second guess.

From the RBNZ's perspective, should it really drop the OCR down a lot from here (some bank economists suggest it should go as low as 2.5% by the end of this year) when the signs are starting to show that the rate reductions already in place ARE starting to work?

Pivotal RBNZ review

The next RBNZ review of the OCR on May 28 will be pivotal. A further cut from 3.5% to 3.25% appears almost certain. But what the RBNZ indicates it will do next beyond that will be very interesting.

House market activity as measured by new mortgages is rising. The last time mortgage rates were low, this fired up the market. Now, admittedly we appear to be a very long way from such a situation at the moment. But the RBNZ would nevertheless not want to risk future recurrence of that at some point further down the track, nor would it want to see inflation start to meaningfully blip up again.

Banks would probably like to see continuing OCR falls so that they could continue to push down their mortgage rates and be able to compete to keep growing their market share, and hence profitability. Without further large falls in the OCR, it's hard to imagine banks pushing rates much lower than they are, although my hunch is we will still see rates in the low 4s by the end of this year.

Obviously much hangs with the RBNZ. It has to decide how much momentum the economy can start to build based on the OCR reductions we've already seen. Or whether significantly more is needed.

To my mind the RBNZ overcooked the speed and magnitude of OCR rises on the way 'up'. We wouldn't want to see it do the same in reverse on the way down.

*This article was first published in our email for paying subscribers early on Friday morning. See here for more details and how to subscribe.

69 Comments

Most of the majors have 1 and 2 year 4.99% now to get to 4.25% we need 75bps of OCR cuts, and we need to not see international rates rise. I think 25 is widely expected this 28th May, so then we need 50bps over the next 7 months, highly likely based on how set in this recession feels. There are four more rate meetings this year.

Rates are rising enough that for the average mortgage about 7-10bps of cuts just about pays the increased rates bill, Electricity is the one to watch over winter. OCR rates cannot fix lack of electricity and it massively impacts business confidence, especially in power intensive regional processing plants. There is no growth growth growth without energy.

It Willis runs a no frills budget the OCR may have to go much lower. If the US goes into recession, implying most other countries also go into recession, the OCR will need to go even lower still, the next major crisis may see negative rates. That would get interesting as banks would need to pay to park money in ESAS.

The market needs 2.99% mortgages, to stem the NZ Housing market crash.

At the current cost of funds, the market will continue to slide.

Implies another 125bps after reaching 2.5% OCR end of 2025, plenty of wood to chop in 2026.

If global recession hits our tourism falls, diary prices drop etc etc current oil prices do not imply a booming global economy

"The market needs 2.99% mortgages"

It's not often that we agree Gecko, but yes, indeed. So now you know exactly how low the ORC will fall, because it will be dropped to a level where the market can function, it's just a matter of time !

Can't a market function by just returning prices to a historic norm. Say three times salary of the buyer - average house price on $300,000.

It might be a bummer for current owners (myself) who will no longer be $ millionaires but I reckon my adult children would prefer owning a house today than waiting for both me and the missus to kark it.

There is more to the market than Real Estate, Singautim. Interest rates will drop to a level where our "economy" will function. Maybe that's more clear for you.

Don't be such a miserly pessimist Yvil.

The NZ market crash, is well on its way back to 3x to 5xDTI.

-Give the youngins a fair suck on the sav, to hell with your amassed housing hoard.

I think people overplay the economy-saving potential of cheaper mortgage costs.

Firstly, people need to ignore the new mortgage card rates - it's all about the weighted average (effective) interest rate, the total mortgage stack, what people are actually paying, and how those payments compare to incomes and other costs (David admirably covers a lot of this above).

Now, interest charged on the total stack of mortgages in March 2025 was just over $4,000 per capita (on an annual basis). The economy flipped into slowdown mode in mid-2023 when interest per year per capita sailed above $3,000 (figures adjusted for inflation). You can see the historic track here. Note that the economy ticked along 'OK' with interest charged at around $3,000 per capita between 2012 and 2019. Another angle on the same issue here - scheduled mortgage payments as a % of gross earnings.

Now look at how banks have managed changes in the OCR before. To get annual interest payable back down to $3,000 per capita we would need an effective mortgage rate of around 4.3%. That would rely on the OCR being below 2% (and quickly). Meanwhile, insurance, rates, and energy costs are pulling hard on disposable incomes, and real earnings growth has stalled.

One of many reasons why I don't see any phoenix-like rise from the ashes this year. 2025 will be all about stagnation (and most commentators will be scratching their heads as to why).

Wow its interesting how long the lag is in the interest paid per capita, after the OCR cuts occur. While I know most people play 6 and 1 year rates, that chart was an eye opener. I cannot see increasing pay saving NZ and do not believe that National can afford (or want to ) cut income tax here. After seeing this chart I am supportive of a 50bps cut this 28th May.

I am still seeing immigrants that have just got there NZ residency leaving for Aussie. I think it was always part of their plan. They are younger and see the benefits of Aussie super contributions. Mostly going to Brisbane. A mix of South African and Indian.

Yes, it is dangerously misguided to think that the plummeting OCR got the economy back on track in 2009 and that a repeat in 2025 will achieve something similar. Three things happened post-GFC that were far more important:

- Bill English went big on fiscal for infrastructure

- Import prices collapsed as the global economy tanked, this 'onshored' demand driving domestic job growth (eventually)

- We had a huge offshore global reinsurance payout after Chch - a whopping 11% of GDP flowed in from abroad (equivalent to around a third of total Govt spending or one quarter of total NZ wages)

These three things combined to tide the ecomomy over until we started borrowing loads of cheap money to bid up the price of houses again.

You also had a common aligned response by the Fed, ECB, China. Now they all hate each other and are engaged in trade wars. This next dip will not sound like the others.

It'll be more like a wave, spread unevenly. Some things that'll possibly happen

- price deflation in some areas, as other regions suck up the excess Chinese capacity from a fall in demand

- growth boost in some regions as the tarrifs alter supply regions away from China

- capital flight, including corporations

- falling demand from America for various industries

- war economies

In theory it should be a great time to put solar on your house.

Possibly.

Although the economics of storing the energy is still "iffy".

Yes, importantly, nz was almost unique in its determination to trigger a large recession in response. 2024 will be permanently scarring.

It is worth considering where those who benefit from reduced borrowing costs will spend their gains...much of it outside the NZ economy.

We don't produce much of our consumption, whether you have surplus funds or not.

No we dont...and we dont tend to invest here either...nor holiday.

So where do we think these additional funds may end up?

There is one silver lining that creates hesitation however.

No we dont...and we dont tend to invest here either...nor holiday.

Clearly an untrue statement. We spend nearly $30 billion a year holidaying domestically, twice as much as we spend going overseas. People have been complaining about tourism and infrastructure, but much of the increased demand is from within.

As for the borrowing impact, travel is the same or higher than it was in 2019, when money was a lot cheaper.

And what does that tell you about the cohort predominating the offshore tourism market

They either have money, or don't care about how much the debt costs to go on holiday.

I'm not sure what your issue is, other than people freely travelling outside the country. Or people buying things not from here. Or what whatever cohort you're trying to talk about get up to.

The issue is where the money (we create) goes... absent the opportunity of capital growth in residential housing we can say it is unlikely to remain here (nor attract/maintain offshore investment) ....and we have an overhang of housing stock.

Why would we anticipate otherwise?

But as said, there is one factor that may change that, and that is the uncertainty that Trumps policies have created...how will those with the wherewithal respond?

It goes many places. New houses, cars (not made here), recreation (more likely here than abroad), new businesses (harder to establish a new business overseas if you reside in NZ).

It doesn't actually look like there's a very strong correlation between our trade imbalance and the cost of money.

Very easy to trade bonds or shares.

So does our propensity to buy foreign shares and bonds increase when our debt is cheaper?

I would suggest the propensity to buy foreign assets increases when we see little possibility of return locally.

So nothing to do with borrowing, and more to do with returns.

You cannot seperate credit creation and return

This is all over the map. How does lower borrowing costs lower returns on domestic investment and increase them on foreign ones?

Circumstance Painter...as stated our sole driver of growth (residential housing) has been exhausted...what is to drive future credit creation domestically and what will those who cash out seek to do with their funds? (remembering the existing stock has already been secured, though not necessarily to the same level)...add to that a state that is at best extremely reluctant to invest in the country and where does the return come from?

There is no growth without credit creation and no (in aggregate) return without same....so where that credit ends up is critical.

As stated (again) there is one aspect that may mitigate, and that is the rest of the world is largely in the same place for the same reasons....too much wealth in too few hands....and why Trump.

This is all general commentary than anything definitive about what happens when money is cheaper.

All I could really say is the cost of credit doesn't have a substantive impact on whether "cohorts" spend money nationally or internationally, for investment or travel. I'd also strongly dispute residential housing is our sole driver of growth.

When debr is cheaper, I'd argue it chases more tenuous or marginal returns. If the OCR is 5, then mortgages are 7-8%, and business loans are closer to 11-12%. So if you're borrowing for commercial purposes, your business is going to want to be attaining net margins of 20% or higher. When it's half of that, you can pursue investments that are either long shots, or of lower profitability - growth, but of a lower quality and sustainability.

I don't think it matters whether that investment is domestic or international.

So you dont think it matters how much of the 'money' supply remains onshore....difficult to trade anything if the funds created are no longer in the country and why (as a debtor nation) we value offshore investment so highly.

"When debr is cheaper, I'd argue it chases more tenuous or marginal returns. If the OCR is 5, then mortgages are 7-8%, and business loans are closer to 11-12%. So if you're borrowing for commercial purposes, your business is going to want to be attaining net margins of 20% or higher. When it's half of that, you can pursue investments that are either long shots, or of lower profitability - growth, but of a lower quality and sustainability."

It may, but ultimately what it also does is increase asset values to the point they feed into input costs creating increased costs and subsequent reduced competiveness and why I say it is distribution that is the driver....cheaper credit may be fine for a broader economy IF (and only if) the ability for assets to be bid up beyond the ability of the wider economy to service is controlled...and it hasnt been for decades and we are now living with the consequences.

"I'd also strongly dispute residential housing is our sole driver of growth."

What other sector would you nominate?

https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/statistics/series/registered-banks/banks-asset…

So you dont think it matters how much of the 'money' supply remains onshore.

As a general rule, it's better to earn more than you spend. But this doesn't really add anything to your "if debt gets cheaper the money will just be invested offshore or turn into holidays" claim. We are now having a totally different discussion.

we are now living with the consequences.

My position is the actual consequences being felt are those of being another first world nation who is unable to be competitive against a global market where there's a raft of alternate producers operating with insurmountable cost disparities. Asset price inflation being a bi-product of attempts to spur growth via debt, in lieu of viable commercial prospects.

What other sector would you nominate?

Well, our exports have grown in line with our GDP growth, for a start. You have to earn some sort of income to service debt, so can't discount that as a GDP driver, otherwise you're funding debt with debt. Not that that doesn't happen to an extent, but the trope of "we're just a house trading economy" is fairly far from truth. It's a factor, granted, but not THE factor.

You may wish to continue to view an economy in isolated segments but that does not reflect the reality that it is interconnected and changes in one segment are not isolated from the the rest.

I take it from your reply that you are nominating exports as the sector that will provide the additional credit creation in NZ which poses a couple of issues...firstly exports as a percentage of GDP have been declining for years and secondly exports are derived from business and rural investment and you may note that credit to both sectors has been flatlining for years so again, what sector do you see creating credit growth in the NZ economy?

https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/new-zealand/exports/#:~:text=Exports%2….

As is evident residential housing is not looking a candidate and nor is government spending

Frank, you're all over the place with your comments, it's hard to follow the point you're trying to make in relation to interest rates.

Is relatively straight forward Yvil...see above.

It takes a steady hand to guide us through the economic headwinds that are currently afflicting NZ. Like a huge ship, it steered too far one way in 2020 and took far too long to correct. As house prices sky-rocketed, it over-corrected the other way almost collapsed the economy in 2024. Now it is lurching back in the other direction and runs the risk of over-correcting again to the point where the economy over-cooks and house prices take off yet again (in 2026).

Given current settings, our economy is a dead duck without private debt growth of at least 6% of gdp per year. And, that, I am afraid, relies on the housing ponzi starting up again.

Or some other mass spending plan. Government infra spend, natural disaster, some sort of global event.

But yes housing Ponzi is the most predictable.

No matter how you slice it though, even what we have now is dependent on future leveraging just to sustain itself. So the actual level of prosperity we can attain/sustain is always obfuscated.

Yes, my cavet of 'current settings' was intended to convey that. We should be doing a major public investment cycle to lift the economy out of the gloom and transition our infra to the 21st century.

You'll get that short term GDP boost while we build, but the return on the investment may not be there.

I'm not sure what 21st century infrastructure looks like. I'd have thought it's a lot more about digital than physical improvements, and our telecommunications is pretty fair to good, all things considered.

We need the infrastructure to re-balance our economy - particularly offshoring less of the demand driven by our consumption. So, what infrastructure do we need to dramatically bring down electricity costs, or reduce oil consumption? What institutional infrastructure do we need to prevent us sending $8bn a year to offshore bank equity holders? At the moment our economy is only viable when we are expanding the private sector balance sheet by a couple of percentage points above GDP growth. We need to internalise demand.

Do we have modern examples of big renewable energy infrastructure spends that dramatically lowers energy prices, once you factor in the cost of the infrastructure?

Because it does seem that's often a fairly elusive undertaking.

We have plenty of historic examples domestically! I would measure the cost of the new infrastructure in hours of labour and tonnes of materials. As a country, we are currently 'spending' millions of those hours and megatonnes of our materials on activities and products we don't need.

Historically we do, and then we increased our renewable generation to nearly 90%. So you're talking about firming up the remaining 10%, which becomes a diminishing proposition - how dramatic an energy price decrease would you expect power to get once that bridge had been gapped?

So it's unclear whether the re-allocation of labour and materials would provide a benefit over and above whatever else we're using it on.

We're using most of our labour on bullshit jobs and our materials on building roads and rick folks' renovations. Get me a pitchfork.

Sounds more like you're after bags of cash to burn, while the private sector is having a timeout.

These are are very common propositions for government spending (green energy and trains), that rarely have an economic case put forward to justify claims of lower energy and transport costs. We'd possibly be better served just increasing budgets of state services.

To burn? Where would the cash go? An investment in our capacity generates public and private jobs. How much of the spend govt taxes back (and from who) are options.

If you were a developer, would you bet the farm on a project today...?

Requires securing land from its current land banker/specuvestor, at a price the dosent stack and only dictated by their greed. That's before you consider cost of development in materials and labour. Plus other cost and risk for the finished product to be at a price the target market can actually afford. In the current economic climate that would require balls of granite, or land purchased/inherited for bugger all. Once the unsold stock has or is on track to be cleared then sure. But that is not today.

Lowering rates again just provides a way to bridge or bail out the over leveraged. Why can the land gamblers never be allowed to face the music?

Or are we just a casino where you are allowed to double or nothing until you win?

Did the RBNZ OCR hikes create the recession or accentuate it?

Cost of living increases (apart from interest costs) were already taking hold and discretionary income was being squeezed...and a significant proportion of the economy rent so why would we expect a reduction of interest costs to have wide ranging effect?

Distribution.

Oh rbnz definitely created it, although higher costs and govt capital spending reductions were supportive.

Our private debt was 160% of GDP. Increasing interest costs by 400pts drove a transfer of 4%×160 = 6.4% of gdp from spenders to savers and bank shareholders. That's about $28bn a year in today's momey (a sixth of total wages!!)

Important to recognise that our high private debt and current account deficit amplified the impact of the rate hikes - making our settings the most restrictive in the oecd.

The cost of living crisis had already begun before the rate hiking cycle so i assume you are attributing the credit boom created prior as being the responsibilty of the RBNZ and the subsequent cause of recession.

The whole world experienced a near 30% shift in the price level over 2 - 3 years. Our import and export prices, our CPI, rent, and critical input costs like oil prices have all made the adjustment. Indeed, our wages got most of the way there too. We described this period as a 'cost of living crisis' and attributed blame to local villains. As if tiny little NZ doesn't just blow in the wind of global prices.

It can be perceived as a much more controllable problem if you create a domestic cause.

But it'll be both, the ramifications of COVID made production more expensive everywhere, in similar way.

If the whole world experienced a near 30% shift in price level and we agree that these 'winds' are beyond the control of the RBNZ and that those price increases impacted discretionary spending then I fail to see how you can attribute more than a accentuating role to the RBNZ to the recession.

Wages by no means kept up, especially with the cost of housing, but nor food or transport. (housing increased 14% q1 2021-q1 2022)

The RBNZ accentuated (or accelerated if you prefer) a recession that was underway

Yup. Speculation overshoot. Just look where the complaining is coming from.

Wages did keep up over the period. Look at your figures again and extend the period into 2024. Wages always respond to price and cost of living increases (and rents then respond to wages). Worth noting here that the cost of living includes mortgage payments. When RBNZ hiked rates they put upwards pressure on wages!

RBNZ did not have to respond as aggressively to the global shift in the price level. They will be using RBNZ as the case study in macro classes in the future - how to completely mess up your response to a global slump and price shock. Orr's hero complex.

K...fair points...4 years is a long time for cohorts with zero (or near) savings to wait for a catchup however....the damage is done long before then.

Some economists are pushing quite aggressively for more and faster interest rate cuts. But would that help?

YES.

I'm picking we'll see another 100 points come off the one and two year rates before any meaningful turnaround on Main St.

But then again, I thought Chippy would be gone by last Christmas.

Add about 18 months after that based on the JF Charts, the lag is MASSIVE. Like the Budget predicted surplus the recovery seems to keep moving out a year, each year.

I think most NZ views are optimistic and do not factor in a US recession, let alone a global one.

There are many countries that are in a bad fiscal position , the Moody's revaluation of US debt is likely to be the tip of an iceburg.

Chippy will get replaced closer to the next election. You want your fresh face, to be as fresh as possible.

If Labour do it now they have to take the vote to the party and unions, if hippy runs out of gas, in the 3 months before the election I believe the sitting members can vote just as Jacinda was put in......

wrong article

To much debt underpinned by insufficient and reducing income.

The US has the same issue with the leveraged gambling on thie share market bordering on insanity. Now a credit downgrade whose impact has yet to unfold. Watching closely to see wether ripples of that wash up her as a floor on further debt debasement bailout for speculators.

End of the day business models relying on interest only are great...until they are not.

🍿

AFR: Australia on verge of house price boom: economist

History suggests that once the RBA starts cutting, property fever hits quickly. One prominent expert says a 10 to 15 per cent price rise is coming.

Has anyone worked out the extra discretionary income people would have if interest rates fell and the savings were used in more productive parts of the economy rather than captured in non-value-added house price increases?

Nice thought. The reality is would that actually happen. Or would it simply be diverted into higher rents (as happens often) or translated into greater bank debt on acquisition of an asset?

According to economist Richard Werner - rates follow GDP. In other words rates are a lagging indicator not a leading one. This suggests that if interest rates are going lower then so is economic growth.

The lack or, to be fair, reduction of direct public investment is a lead indicator - for a Keynesian.

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.