By Matt Nolan*

Last week New Zealand GDP numbers were released for the end of 2021. Although the world has moved quickly since then, with the full New Zealand Omicron outbreak and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it is still useful to understand the past to know where we are.

GDP rebounded strongly, business investment and durable good expenditure shot up, and we ended 2021 with an economy that was 5.6% bigger than it was in 2020. With both household and business investment surging this looked like an economy brimming with confidence and most likely overheating.

However, prior to this release the 1News Kantar poll results came out - stating that 53% of respondents expect economic conditions to deteriorate in the next 12 months.

For the polling in February, it’s easy to understand why we all feel a bit bad right now - the Covid outbreak and war overseas are real crises that make us feel nervous. But these results were already bad in September and November. We didn’t use our mystical powers of foresight to determine these things would happen last year - so there were reasons why we felt uncomfortable then even though GDP numbers were so strong.

Understanding why the lift in GDP in December 2021 didn’t necessarily feel good may give us a further insight into why the sharp income shocks in the first few months of 2022 have felt particularly bad.

Perception vs reality: What to believe?

It is easy to put too much weight on perceptions and confidence measures, especially when there is an incentive to tie a political view to it. For every 10 crises we get told about on a regular basis, only one exists and an extra one isn’t mentioned.

So instead, let’s start this the way we’d want to look at any problem - by looking at the tangible data.

Adjusting for seasonal effects both GDP and consumption have rebounded in the December quarter - to their second highest and highest level on record respectively. Earlier data on the labour market indicated that unemployment was at its lowest level since the HLFS began (1986) while labour force participation remained at a historically - and globally - high level.

With job security and job opportunities both freely available, we would normally expect people’s perception of the future to be bright. And high GDP indicates high incomes, on average, in the economy. This is even reflected in the willingness of people to take on irreversible investments, with a strong increase in business investment and household durable good spending.

But in many ways these things only matter in so far as we feel comfortable and able to consume, as a result it is useful to look more carefully at the spending by New Zealand households.

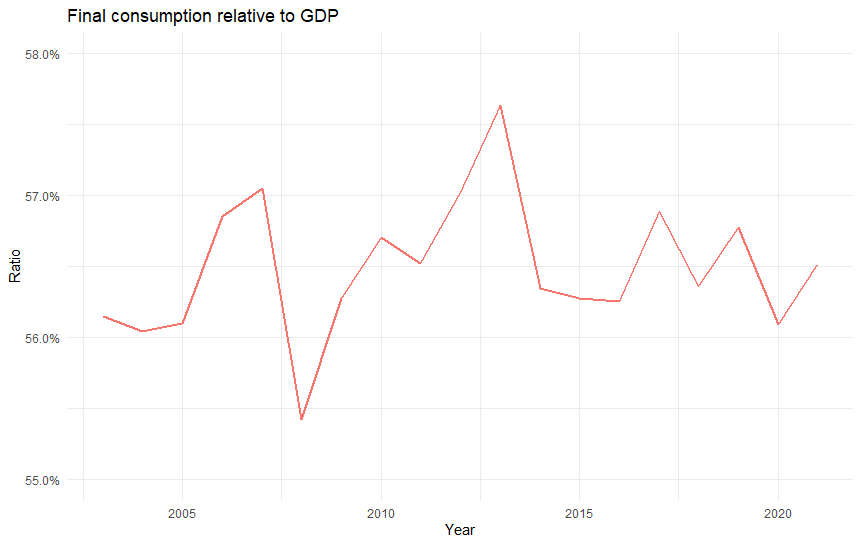

First let's have a look at consumption’s share of GDP. By looking at this we can get an idea regarding how much income is being used to purchase consumption goods and services.

From this we can see that consumption’s share of GDP did increase in 2021, but is still relatively similar to other years. The effects of high prices, deferred demand for durable goods, and the general inaccessibility of many service based products or all issues that appear to have canceled out when we look at consumer spending at an aggregate level.

As a result, if we want to understand the nature of consumer experience a bit more we can’t just look at the value spent out of income - we need to consider both the amount people are spending on consumption and the volume of consumer goods and services received.

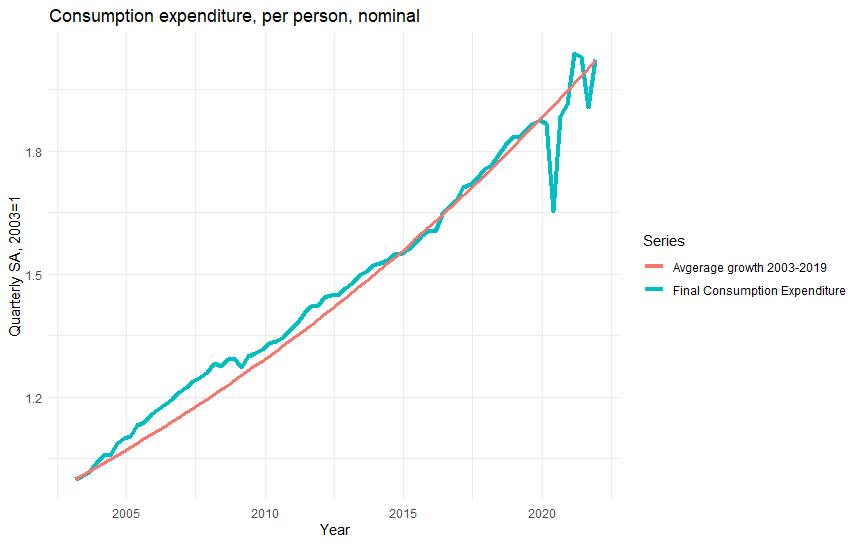

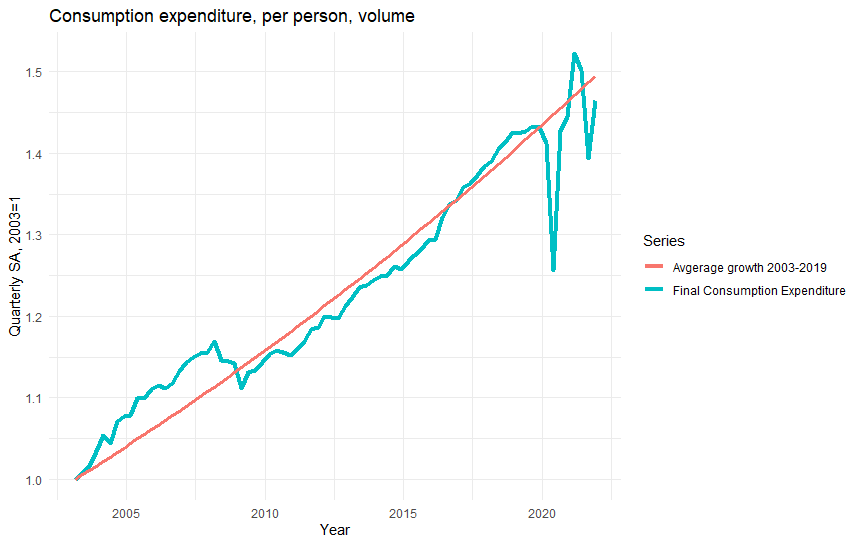

If the value of final consumption had continued to grow at the same rate it was prior to the Covid outbreak, then the December figure looks like a return to normality. However, the actual volume of consumer goods would have fallen significantly behind that trend.

Record high GDP, employment opportunities, and signs we would open up to the rest of the world should have led to plenty of positive vibes. And yes, New Zealanders are now able and willing to buy more than they were prior to Covid.

However, it didn't feel nice spending more dollars on products - and the higher prices have meant that the increase in consumption opportunities that individuals have been used to receiving through time have not occurred..

The way we can understand this is that the price rise is the way of distributing the burden of the income shock that New Zealand has been through, and in this way the pain we all feel through higher overall prices is part of how this loss has been paid for.

Fixed yielding assets, bank deposits, and situations where we feel we really need to replace an old car or washing machine make this lift in prices feel really bad - and the burden of any inflation tax always falls on those who are unable to protect themselves from these changes in prices.

As a result, seeing prices rise while we are uncertain how we’ll fill the gap - are we going to be able to earn more from our savings, is it a good time to replace home appliances when they seem so costly to get in, and will we be able to negotiate a wage increase - is a justifiable reason why people started to feel like they were going backwards, even as all the indicators point to a strengthening economic position for most households.

Inflation refers to persistent price growth - and it is a process that takes place when people are trying to protect themselves from this implicit tax. In this way, the recent GDP numbers tell us that the RBNZ and government need to be clearer about how their monetary and fiscal strategies will work to prevent inflation, and fairly share the burden of the crisis the country has been through.

Why 2022 is different

When the shock is on specific prices, like fuel, things are a bit different - and that is how 2022 has felt so far. Here a specific item is more scarce, and the higher price represents this. Plans to mute this increase by cutting taxes are unfair - as they involve forcing people who aren’t using the fuel to pay for it.

However, those who currently make significant use of fuel, are unable to find alternatives such as public transport, and whose budget is already stretched, face a disproportionate cost from this price rise. Rosie Collins rightly notes the importance of people substituting away from their reliance on fuel. But in the short term, this is a reduction in income - and so her suggestion for direct income support for those who are most vulnerable is a good one. Income has been lost, and it isn’t fair that we demand it is the most vulnerable in society that pay for it.

Tying this back to demand pushing the economy past excess capacity, such income support increases overall demand - and so monetary policy will need to tighten further in the face of this support.

This monetary-fiscal coordination is normal - monetary policy determines price growth and the price level, while fiscal policy is in charge of distributional considerations. Either cutting fuel taxes, or giving a payment to those who are in a vulnerable position due to price change, are transfers that support the incomes of households and those that the households purchase products from.

By increasing demand for goods and services this should also generate a response from monetary authorities in their goal to balance aggregate productive capacity with demand, such as through higher interest rates. These higher interest rates (other things held constant) similarly lower the incentive to borrow and timing of expenditure on durable items, and if people currently borrowing are more sensitive to income changes may influence overall expenditure as well.

Given the high level of demand for durable goods at present such monetary policy may be especially effective. In this way, the effective and equitable way to deal with the negative income shock New Zealand faces involves appropriate government support to the most vulnerable in society, alongside monetary policy that is consistent with medium term price stability, and clearly informed households and business that understand the nature of the shocks New Zealand is facing and can make their own considered choices.

But this brings us back to our concern from a couple of weeks ago - monetary authorities have to act in a way consistent with this, and communicate it.

If the fiscal authority decides to spend without increasing taxes or cutting spending elsewhere, the central bank needs to tighten monetary policy. If this involves a path of higher interest rates, and it is due to a mix of income shocks and government spending intended to support the incomes of those facing these shocks this needs to be spelled out explicitly.

When income has been lost due to an income shock, neither the government or the central bank can make it reappear from thin air. All they can do is determine who faces the burden of that shock.

To repeat the punch-line of the prior article a bit more directly, if the central bank doesn’t start to more actively communicate what is going on, and indicate that persistent inflationary pressures are not a fair way for the burden of this shock to be spread, then this is how the burden will be spread.

*Economist Matt Nolan is a research manager at e61, an Australian not-for-profit economic research institute, and blogs on the TVHE website.

20 Comments

I could explain this in one or two sentences rather than a whole article.

The December 2021 lift in GDP was simply a dead cat bounce, a response to the lockdowns.

There!

Speaking from my own experience, I saved up quite a lot of money in lockdown, and I spent quite a lot late in 2021. The main reason for that was inflation, and wanting to get a few things that I needed immediately or foresaw a need for in the next 1-2 years, before prices rise a lot.

Don't know how common this behaviour was, but it might be quite common.

I didn't really save much as my income tanked as wage subsidies and reductions took effect for the lockdown periods, unfortunately. So delayed gratification for some, no gratification for others maybe?

Also the inflation we are seeing now isn't new. We got told it would just be transitory for a couple of quarters and now it's patently not. So we've had a while of coping with rising prices.

We are yet to see the inflationary spikes from recent lockdowns across China's industrial hubs and ports

Bringing tens of thousands of tourists, foreign workers and students into NZ within a span of months will also stimulate inflation in the short run by adding further demand pressure on consumer goods and temporary accommodation.

Inflation is essentially just a flat tax (pretty much exactly as ACT proposed, just instead of ACT’s 20% Labour has decided that it should be 6%) on every dollar with no adjustment based on how much you earn. If you can stash wealth in inflation resistant assets that rise in value when there is inflation then you are effectively exempt from this tax.

I'd swap my effective tax rate for a flat 6% any day of the week, this has to be one of the worst analogies I've seen.

If the govt had to add 6% of taxes would you prefer it be a flat tax via inflation or made progressive so that rich people who make over 55,000 a year pay more of it?

It's a bad analogy because inflation is nothing like a flat tax. A tax is revenue for the government, that money actually goes somewhere and can be used for something. Inflation destroys the purchasing power of existing money, sure everything costs more but no one is any richer for it, its just value being destroyed. Savings are eroded, incomes are stretched further. Its nothing like a tax. And i wouldn't call anyone who makes 55,000 a year rich, the tax brackets in this country are absolutely ridiculous.

It changes the distribution of wealth between asset owners (such as the government) and those without assets (such as beneficiaries).

Care to explain how inflation affects wealth distribution?

Person A & B both have $100. Person A buys a commodity such as gold. Person B holds cash. 10% Inflation occurs, gold is now worth $110 whilst cash is still worth $100. The wealth distribution has swung in Favour of the asset holder.

in reality person A likely has assets because he has more disposable wealth than person B so the rich get richer and the poor become relatively poorer.

There are some interesting charts (will see if I can find one) in the wealth that would be built if you could time the markets perfectly and swap between growth assets and gold when markets turn. The return over the general market is massive in terms of real buying power.

Interestingly is that periods of high inflation have generally resulted in reducing wealth inequality......but you would think that the rich would simply get wealthier because they put their assets in 'inflation resistant assets' as you propose.

Perhaps its because they put them in the wrong assets that they think are inflation hedges?

Interesting. I did some research on googled articles and They show that a rise in inflation can both reduce inequality or increase inequality, depending on the initial inflation rate. Rising inflation is associated with a decrease in inequality for low initial inflation rates and with an increase for high initial inflation rates.

https://www.cepweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/CEP_WP_Inflation_and_…

Its possible we're following the long term cycle (happens every 80-100 years) and now living in a similar period to the 1920-1940's. Wealthy people own a lot of assets and when inflation is near zero, then discount rates applied to the future cash flows of assets are very low so you end up with very high asset prices and hence rich people getting richer and a big divide between the rich and the poor.

However if that cycle reverses, and inflation keeps rising, then interest rates keep rising and the discount rate applied to the future cash increases which decreases the price of the asset - and a relative drop in the wealth of those who are rich/asset owning.

You can see that dynamic playing out in this chart over the past 100 years. We might now be restarting the 1945-1980 cycle where we have rising interest rates for the next 30 years, which put a cap asset price appreciation because discount rates applied to future cash flows of assets keep rising.

Just a theory.....but based upon reading books by the likes of Shiller, Dalio, 4th Turning generational theory etc.

Debt can also be reduced by inflation, so that may improve equality.

"such income support increases overall demand - and so monetary policy will need to tighten further in the face of this support."

The slavish devotion to monetary policy is admirable but flawed. Two reasons why...

Let's say that we provide income support to people on low incomes to offset the increasing cost of petrol. What happens to overall demand in the economy? The immediate impact would be the resumption of demand for things that people on low incomes stopped buying when they had to pay more for petrol. So, yes, an increase in demand, but only back to the level of a month or so ago. Given that interest rates are not changed frequently, the idea that monetary policy needs to 'tighten' because demand has returned to levels last seen a month or two ago is flawed.

Secondly, and more fundamentally, if aggregate demand did go up because of increased income support for families on low income, why would the response to this increase in demand be a broad-based change to the cost of borrowing (i.e. monetary policy)? If you give one million dollars to low-income families then why not just offset the increase in demand by levying higher taxes elsewhere? Or, even better, look at what low income families are most likely to spend the extra money on, and test whether the supply of those things is constrained (which could lead to price increases)?

Physical consumption cannot keep going exponentially upwards.

So if spending does (keep going exponentially upwards) the difference can only be filled by two things; unrepayable debt, or a lessening of a dollar's value.

End story.

Well, unless spending continually reduces from here on in, to match supply......

Sadly, the financialisation of the global economy now means that there are already far more dollars spent or bet on the price of commodities (real reasources) than there are actual commodities. We are already spectacularly overdrawn, must of us just don't realise it yet.

1/ I don't have an overdraft.

2/ I live within my means.

3/ The only debt I have is my mortgage which I'm paying off faster than the bank requires.

4/ As I structured the mortgage and payments knowing that interest rates could potentially rise to semi-stupid rates, I don't expect to have any significant hardship should mortgage interest rates rise over 12% 4 years from now, so long as there isn't any silliness with employment in NZ.

5/ There would have to be significant increases (double or triple) in commodity prices before that would cause me any significant difficulty.

6/ And my income isn't excessive - I am not a manager or a director or anything over-paid like that. I just have structured my finances carefully and bought before residential property prices went stupid with all the overseas NZers returning back to NZ.

7/ Once NZers start moving back overseas again then I expect that property prices will most likely fall again.

... not all consumption is physical ... increasingly in the knowledge based economy entertainment's which require no physical resources to be inputted absorb increasing quantities of Gen Z's spare time ... no limitations , except time ...

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.