Reserve Bank Assistant Governor Karen Silk says tariff policies could trigger a supply shock in New Zealand and lead the Monetary Policy Committee to pause or end its interest rate easing (lowering) cycle.

This isn’t what the central bank expects—it sees the net effect as disinflationary—but it helps explain why it won’t commit to more rate cuts, even though the Official Cash Rate projection suggests they’re needed.

Some economists saw Governor Christian Hawkesby’s comments as hawkish, but Silk says that was only because markets were already strongly biased toward further easing.

“If people sat back and looked at what we’ve said, it's quite a balanced view that's sitting in there, and that's what we're trying to convey,” Silk told interest.co.nz.

“There’s all this uncertainty about how the global story is actually going to play out, and it can have upside or downside effects on inflation. And what are we concerned about? Inflation.”

Uncertainty will weigh on domestic investment and spending in the short term. But the 225 basis point cuts to the OCR so far are expected to have more impact later in the year.

The interest rate track in the Monetary Policy Statement suggests the committee may need to cut once or twice more in the central forecast. But members will be watching closely for any signs of a tariff-driven supply shock.

Memories of inflation from the pandemic supply shock are still raw, and the central bank’s mandate has been trimmed to double-underline its already strong focus on price stability.

Silk said the bank had assessed the net effect of trade disruptions as disinflationary, due to the hit to confidence and demand, but wasn’t ruling out other possibilities.

“We’re talking about a shift in trade patterns globally. And when you have a significant shift like that, there's always the potential that you can get some supply side effects coming through.”

There are already some unwelcome trends in the inflation data. Headline inflation is forecast to rise to 2.7% later this year, and inflation expectations have also crept higher.

Core inflation is 2.5% and falling. The central bank believes there is still plenty of spare capacity in the economy. Yet rising food prices and tariff news appear to be capturing the attention of a public still sensitive to inflation.

Silk was quick to point out these measures were still consistent with inflation staying within the target range and anchored at the 2% midpoint. But she said those conditions needed to be maintained, which may be contributing to the committee’s more balanced view on rate cuts.

Paul Conway, the Reserve Bank’s chief economist, said the rise in headline inflation was partly driven by higher electricity prices—due to increased transmission charges—and volatile food prices.

“Inflation expectations have nudged up across the board, which is not ideal, but … we don't see that increase in near-term inflation getting embedded and pushed out into the future.”

Ultimately unsure

If the economy unfolds as predicted in the Reserve Bank’s central forecast, the OCR is expected to fall from 3.25% today to at least 3%, and possibly to 2.75%.

But the bank was uncertain enough to present two alternative scenarios: one with the OCR rising to 3.5% to counter a supply shock, and another falling to 2.5% to offset weak demand.

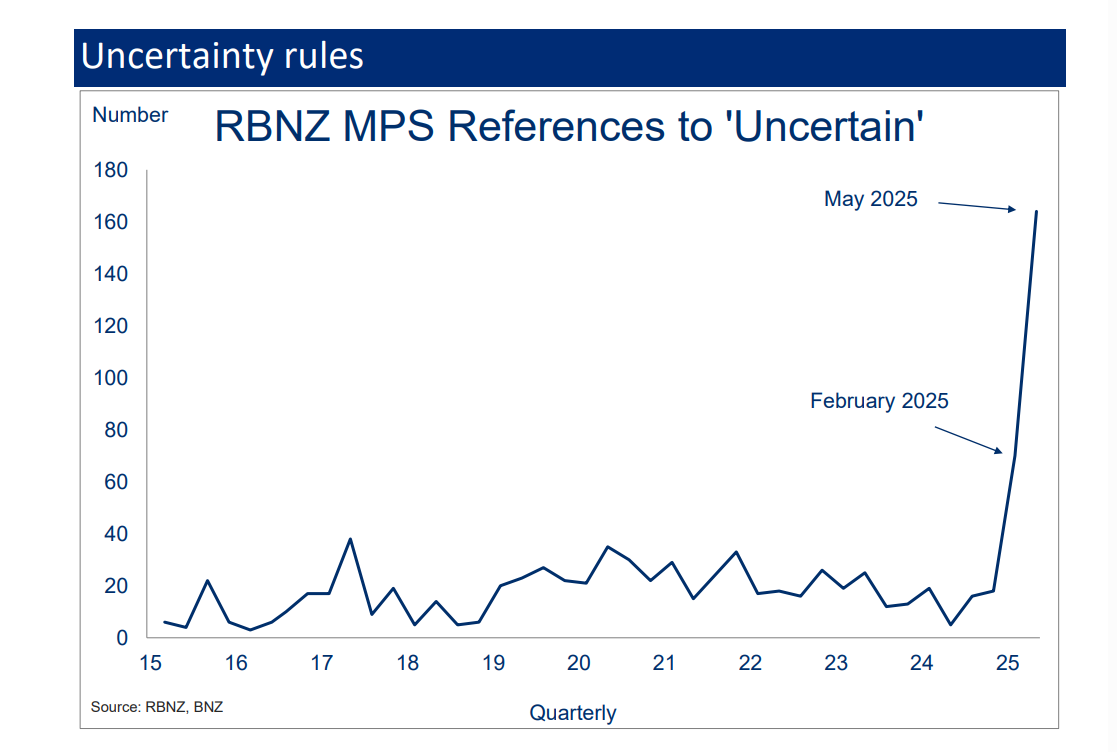

Stephen Toplis, head of market research at BNZ, counted 164 uses of the word “uncertain” in the 50-page Monetary Policy Statement—enough to create a hockey stick-shaped graph.

It also included new measures of uncertainty, such as Sense Partners’ analysis of how often news articles meet defined criteria. That measure showed uncertainty at levels seen during Covid outbreaks and the global financial crisis.

The New Zealand Institute of Economic Research’s business survey found firms were more uncertain than during the 2020 pandemic, but less so than at the start of 2024. Another data set measured the gap between professional GDP forecasts and showed a relatively strong consensus.

ANZ released updated forecasts on Thursday, but they were little changed from April, when the bank downgraded its outlook for economic growth and the Official Cash Rate.

But they warned it wasn’t possible to create a central forecast that captured the “low-probability, but high-impact risks” now characteristic of the global economy.

“It’s fair to say that a lengthy discussion of the above forecast tweaks would very likely leave us splitting hairs over minor macroeconomic developments, when it’s still unclear whether the elephant in the room is about to stampede over our entire forecast or wander sedately past in the background—breaking the occasional tree but posing no real threat to our nation’s economic wellbeing.”

“Overlay all of this with lingering global uncertainty, and it's fair to assume forecasters are likely to get a few things wrong this year," ANZ's economists say.

Reserve Bank Governor Christian Hawkesby told Parliament's Finance and Expenditure Committee he believed the central bank was well placed to respond to any events that might shift the forecasts in either direction.

“We've got core inflation measures trending to target [and] we've got interest rates near neutral. That gives us lots of room to manoeuvre. So, if things get better or worse, we can respond to that."

*This article was first published in our email for paying subscribers. See here for more details and how to subscribe.

4 Comments

If the RB are going put a margin of safety on the OCR just in case there's another supply shock, I hope they've done their homework on what the material implications will be for the real economy. With the economy currently vulnerable to diving back into recession, it won't take much for that to become a reality.

I dont see the velocity of money mentioned often during crisis or recession.

If Vt = PT/M I suppose it can to some degree figured through eftpos volume etc. Price levels are being measured much more often now?

What if we need to accelerate and brake at the same time due to conflicting factors?Do your best to minimise collateral damage, spray and walk away and write memoirs like Bernanke?

If we get a supply shock of a critical product or two (fuel, food etc), inflation will follow. The central bank's tools will be powerless - too weak, too slow, too imprecise. I get that Rbnz want everyone to believe otherwise so that they can performatively 'manage expectations' but, the whole thing is a farce.

A question for you JFoe...do you still foresee growth in the residential mortgage market in the short to medium term given the evident current headwinds and if so what do you think will be the mechanism(s) to enable it?

It would appear that the model continues though I fail to see why it would be so given circumstance.

https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/statistics/series/registered-banks/banks-asset…

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please register to comment

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments. Our current comment policy is here.